Welcome Dynamoterror dynastes! This is another very special Fossil Friday for Western Science Center and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. Hot on the heels of our new armored herbivorous dinosaur, Invictarx zephyri comes this new tyrannosaur. Like Invictarx, Dynamoterror lived 80 million years ago in what is now New Mexico and is published in the online open-access journal PeerJ. Dynamoterror is known from an incomplete skeleton that includes bones from the skull, hand, foot, and many other fragments.

This is another very special Fossil Friday for Western Science Center and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. Hot on the heels of our new armored herbivorous dinosaur, Invictarx zephyri comes this new tyrannosaur. Like Invictarx, Dynamoterror lived 80 million years ago in what is now New Mexico and is published in the online open-access journal PeerJ. Dynamoterror is known from an incomplete skeleton that includes bones from the skull, hand, foot, and many other fragments. The first image shows the two frontal bones from the top of the skull of Dynamoterror (left and right) and the 3D-print of the composite frontals created at Western Science Center (center). We made the 3D-print by laser-scanning the actual fossils, building 3D digital models of them, and then mirroring and combining the models based upon overlapping anatomical features preserved on both frontals. This 3D-print helped us refine our interpretation of the anatomy in this region of the skull and is a nifty item to share at public events!Dynamoterror lived at the same time and place as Invictarx and the hadrosaur I have posted for Fossil Friday the last three weeks, and probably was quite a threat to them. Paleoartist Brian Engh has depicted a less than friendly encounter between Dynamoterror and Invictarx in a spectacular piece of artwork.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

The first image shows the two frontal bones from the top of the skull of Dynamoterror (left and right) and the 3D-print of the composite frontals created at Western Science Center (center). We made the 3D-print by laser-scanning the actual fossils, building 3D digital models of them, and then mirroring and combining the models based upon overlapping anatomical features preserved on both frontals. This 3D-print helped us refine our interpretation of the anatomy in this region of the skull and is a nifty item to share at public events!Dynamoterror lived at the same time and place as Invictarx and the hadrosaur I have posted for Fossil Friday the last three weeks, and probably was quite a threat to them. Paleoartist Brian Engh has depicted a less than friendly encounter between Dynamoterror and Invictarx in a spectacular piece of artwork.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur update #2

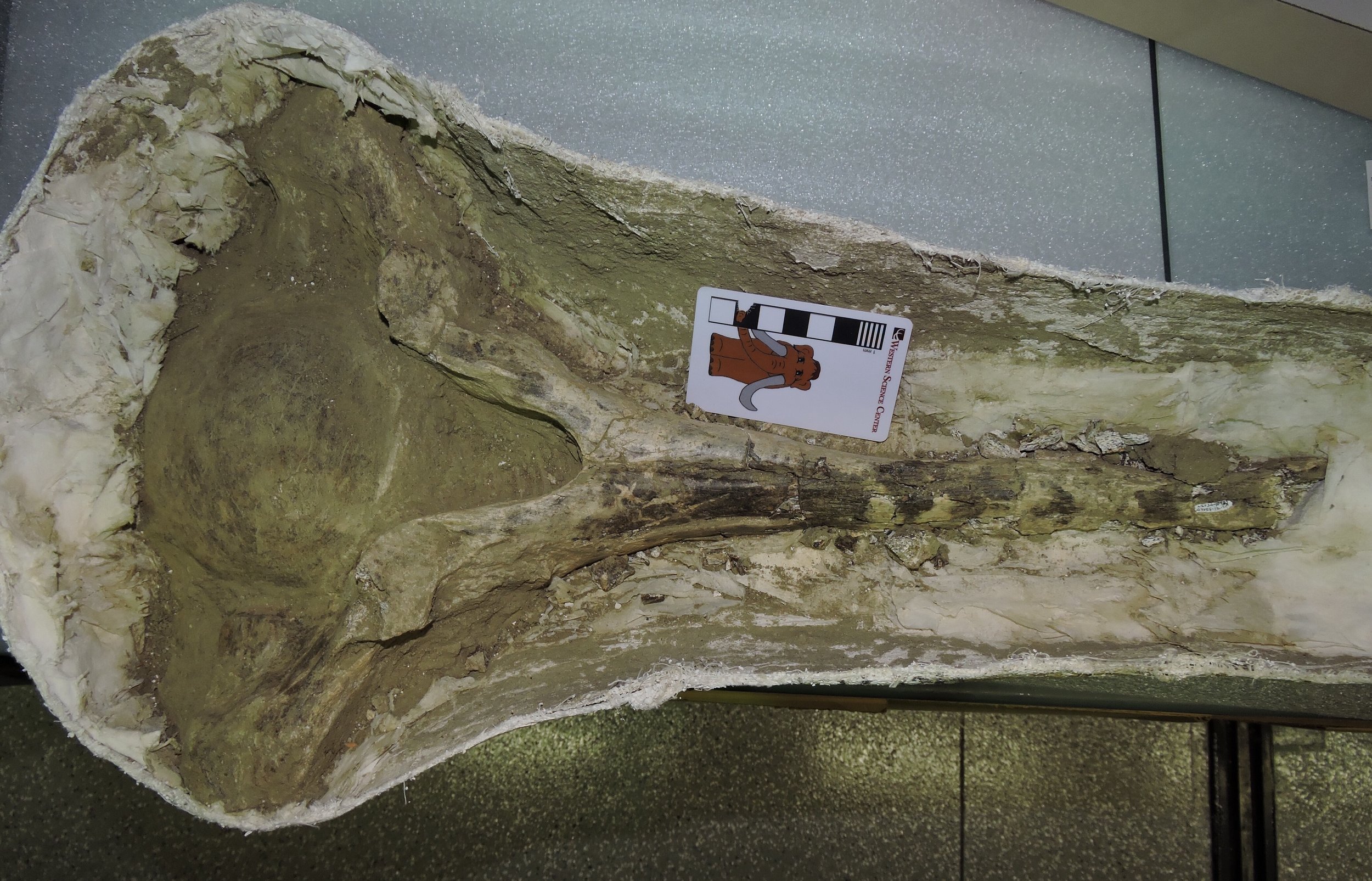

For the last two weeks, I've been giving you updates on the preparation of a big block of rock packed full of hadrosaur bones from New Mexico.All seven bones have now been freed and Western Science Center staff and volunteers are putting the finishing touches on them - removing the last bits of rock, repairing breaks, and reinforcing cracks.

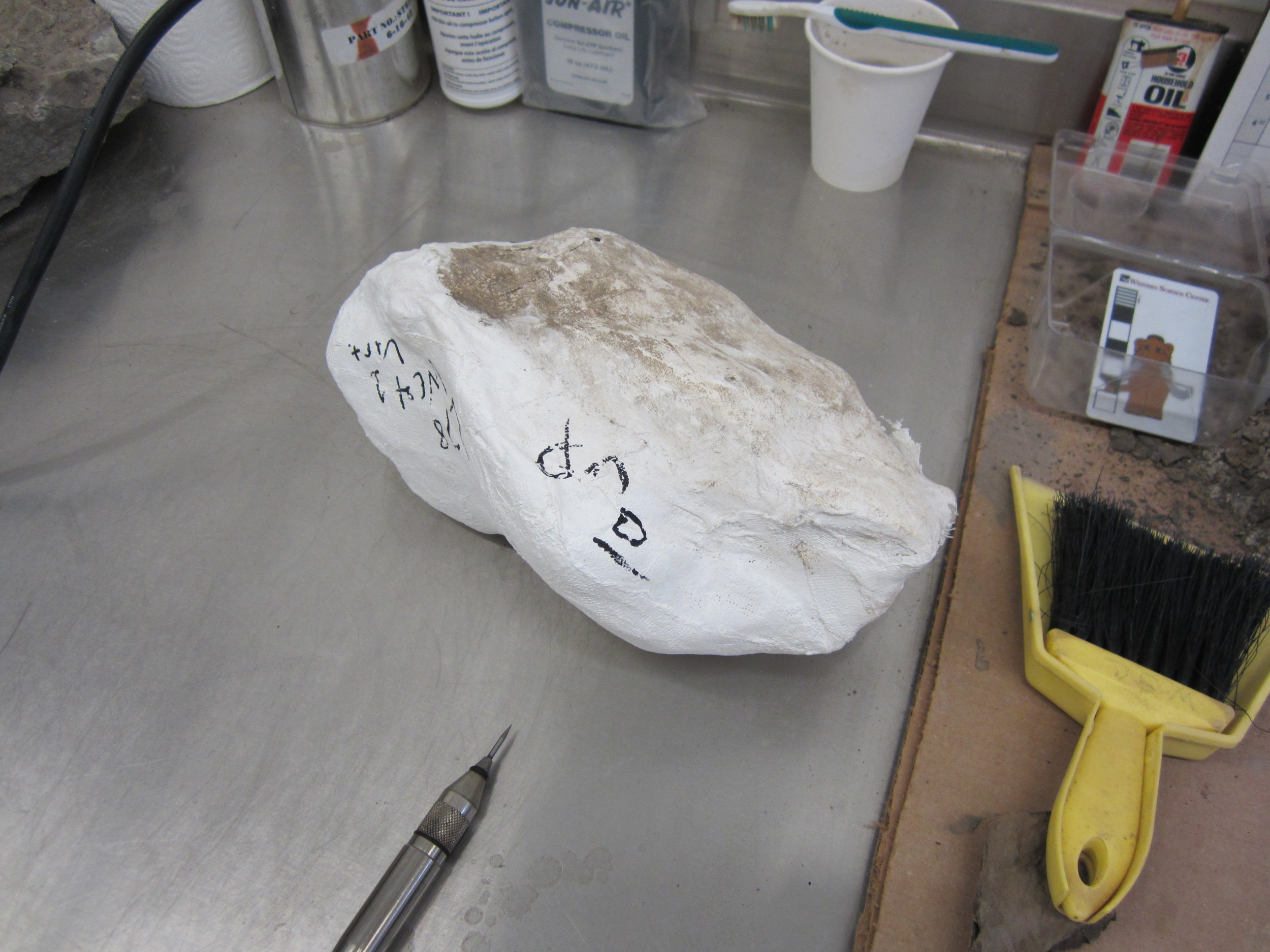

For the last two weeks, I've been giving you updates on the preparation of a big block of rock packed full of hadrosaur bones from New Mexico.All seven bones have now been freed and Western Science Center staff and volunteers are putting the finishing touches on them - removing the last bits of rock, repairing breaks, and reinforcing cracks. Volunteer Joe Reavis, who worked extremely diligently on the big block for over a month, is now moving on to some smaller jackets from the same quarry, starting with the small jacket pictured here. There are two more jackets twice the size of this one! What parts of this 80-million-year-old herbivorous dinosaur do they contain? I'll continue to post updates as more of this remarkable animal is freed from the mudstone. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Volunteer Joe Reavis, who worked extremely diligently on the big block for over a month, is now moving on to some smaller jackets from the same quarry, starting with the small jacket pictured here. There are two more jackets twice the size of this one! What parts of this 80-million-year-old herbivorous dinosaur do they contain? I'll continue to post updates as more of this remarkable animal is freed from the mudstone. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur jacket update

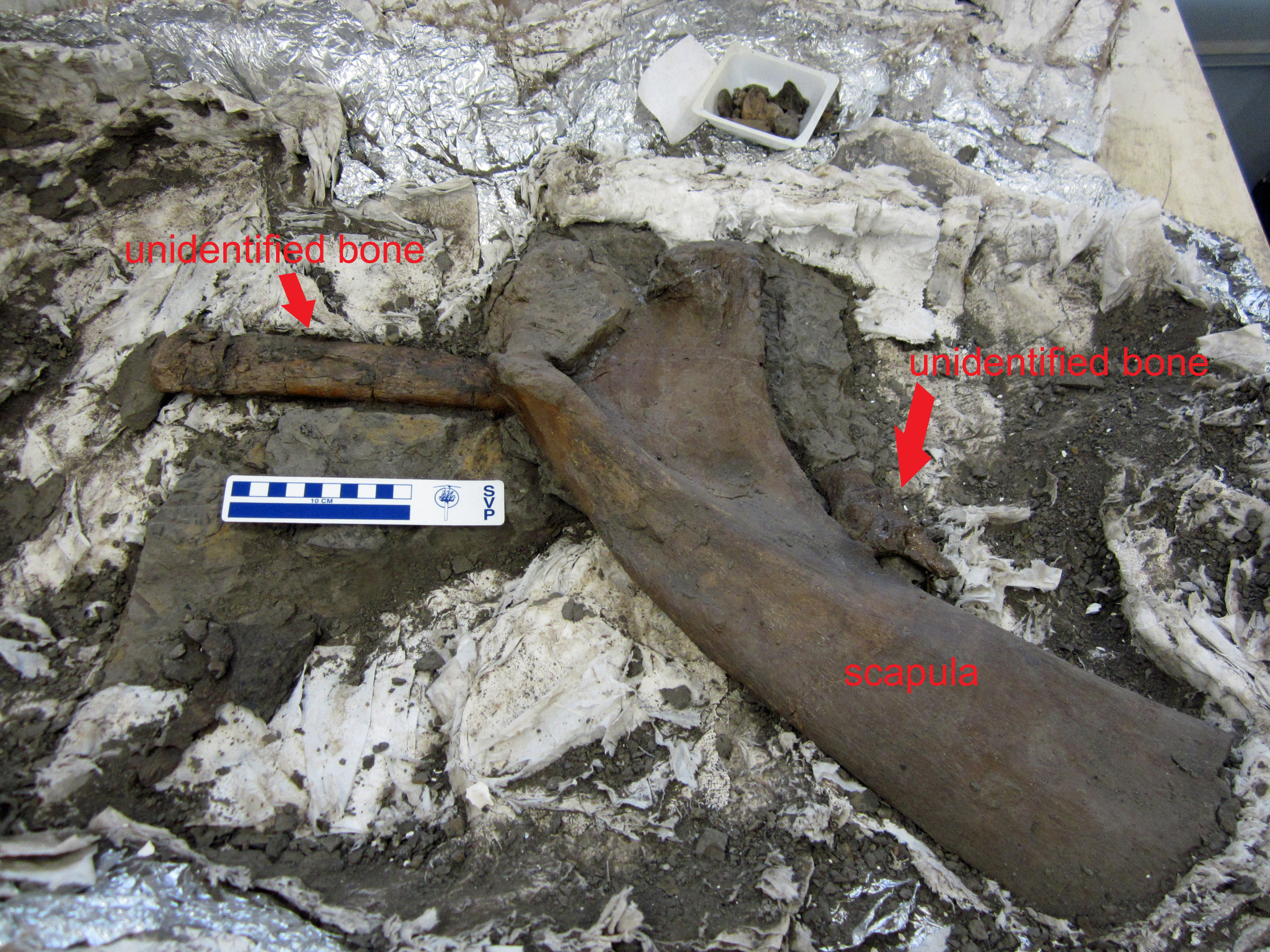

Last week for Fossil Friday, we posted about a big plaster jacket packed full of 80-million-year-old hadrosaur bones, which we brought back to the Western Science Center from New Mexico in June.Volunteer Joe Reavis has been working very diligently on removing the rock from the large but quite fragile bones. Every week brings more progress and greater understanding of which parts of the animal are actually present.Since last Friday, Joe has separated the two forearm bones from the scapula. It was all hands on deck earlier this week as we carefully lifted the two forearm bones away from the jacket, leaving the scapula completely intact. Last week, I identified the two long forearm bones as the left and right radii (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/fossil-friday-hadrosaur-bones/#more-1697). However, one of them is not a radius after all, but is instead an ulna, the other long bone in the forearm.

Last week for Fossil Friday, we posted about a big plaster jacket packed full of 80-million-year-old hadrosaur bones, which we brought back to the Western Science Center from New Mexico in June.Volunteer Joe Reavis has been working very diligently on removing the rock from the large but quite fragile bones. Every week brings more progress and greater understanding of which parts of the animal are actually present.Since last Friday, Joe has separated the two forearm bones from the scapula. It was all hands on deck earlier this week as we carefully lifted the two forearm bones away from the jacket, leaving the scapula completely intact. Last week, I identified the two long forearm bones as the left and right radii (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/fossil-friday-hadrosaur-bones/#more-1697). However, one of them is not a radius after all, but is instead an ulna, the other long bone in the forearm. Finding fossils in the field is not the end-all and be-all of discovery. Instead, it's only the first step. As we continue to clean the bones of this hadrosaur skeleton, we will refine the identities of the preserved bones and eventually start to investigate what kind of hadrosaur we have sitting in our lab.

Finding fossils in the field is not the end-all and be-all of discovery. Instead, it's only the first step. As we continue to clean the bones of this hadrosaur skeleton, we will refine the identities of the preserved bones and eventually start to investigate what kind of hadrosaur we have sitting in our lab. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur bones

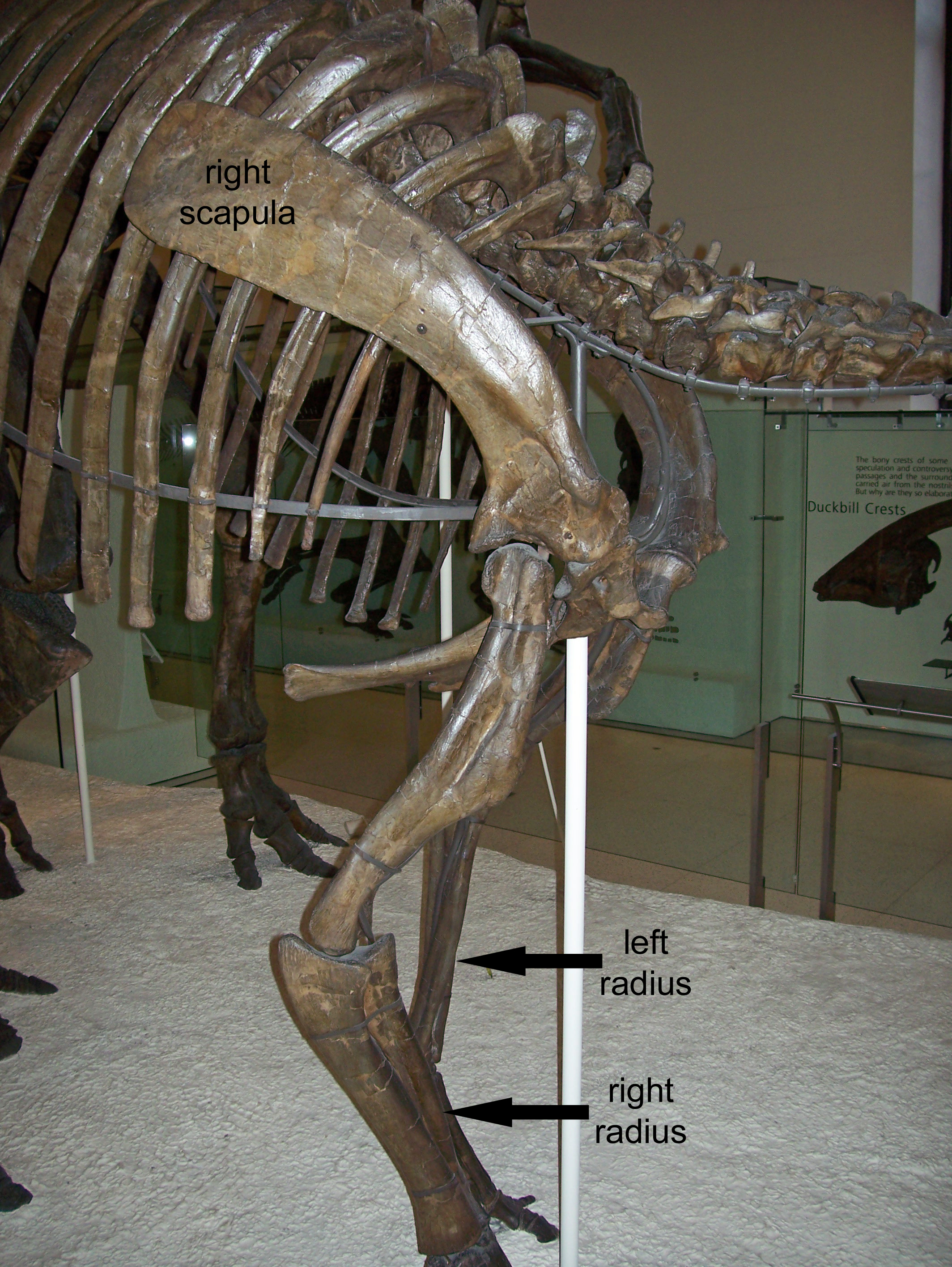

Being wrong is part of the scientific process. Scientists make new discoveries every day, and sometimes prior ideas are supported and sometimes they are refuted as we learn more.Today's Fossil Friday is a perfect example of this, as well as being a really exciting fossil! In June, my colleagues and I returned to the Western Science Center after three weeks of field work in New Mexico. Among the half-ton of 80-million-year-old fossils we brought back was a large plaster jacket containing what I had identified as several bones of a theropod, some sort of medium-sized meat-eating dinosaur.For the last month, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis has been preparing this big block of rock, carefully revealing the bones within. His work has led to a bit of a surprise - the bones are not those of a meat-eating theropod, but instead a plant-eating hadrosaur! Hadrosaurs are often nick-named the "duck-billed" dinosaurs, because of the wide beaks at the front of their mouths. These herbivores could reach 30 feet or more in length and were extremely common in North America during the last 20 million years of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction 66 million years ago that wiped out all the dinosaurs except modern birds.Isolated hadrosaur bones are abundant in the Menefee Formation, the layer of rock we are studying in New Mexico. However, this large jacket contains at least three limb bones in close proximity. So far, Joe has uncovered the right scapula (shoulder blade) and both radii (the radius is a long bone in the forearm). This next image shows the arms of AMNH 5886, a skeleton of the later hadrosaur Edmontosaurus annectens, which I photographed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The right scapula and both the left radius and right radius are labelled.

Being wrong is part of the scientific process. Scientists make new discoveries every day, and sometimes prior ideas are supported and sometimes they are refuted as we learn more.Today's Fossil Friday is a perfect example of this, as well as being a really exciting fossil! In June, my colleagues and I returned to the Western Science Center after three weeks of field work in New Mexico. Among the half-ton of 80-million-year-old fossils we brought back was a large plaster jacket containing what I had identified as several bones of a theropod, some sort of medium-sized meat-eating dinosaur.For the last month, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis has been preparing this big block of rock, carefully revealing the bones within. His work has led to a bit of a surprise - the bones are not those of a meat-eating theropod, but instead a plant-eating hadrosaur! Hadrosaurs are often nick-named the "duck-billed" dinosaurs, because of the wide beaks at the front of their mouths. These herbivores could reach 30 feet or more in length and were extremely common in North America during the last 20 million years of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction 66 million years ago that wiped out all the dinosaurs except modern birds.Isolated hadrosaur bones are abundant in the Menefee Formation, the layer of rock we are studying in New Mexico. However, this large jacket contains at least three limb bones in close proximity. So far, Joe has uncovered the right scapula (shoulder blade) and both radii (the radius is a long bone in the forearm). This next image shows the arms of AMNH 5886, a skeleton of the later hadrosaur Edmontosaurus annectens, which I photographed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The right scapula and both the left radius and right radius are labelled. There is still more rock to be removed in the big jacket, and we brought back half a dozen smaller jackets containing other bones from the same site, one of which contains a hadrosaur vertebra. So, we will have much more to say about this remarkable animal in the future. The fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

There is still more rock to be removed in the big jacket, and we brought back half a dozen smaller jackets containing other bones from the same site, one of which contains a hadrosaur vertebra. So, we will have much more to say about this remarkable animal in the future. The fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Fossil Friday - camel tooth

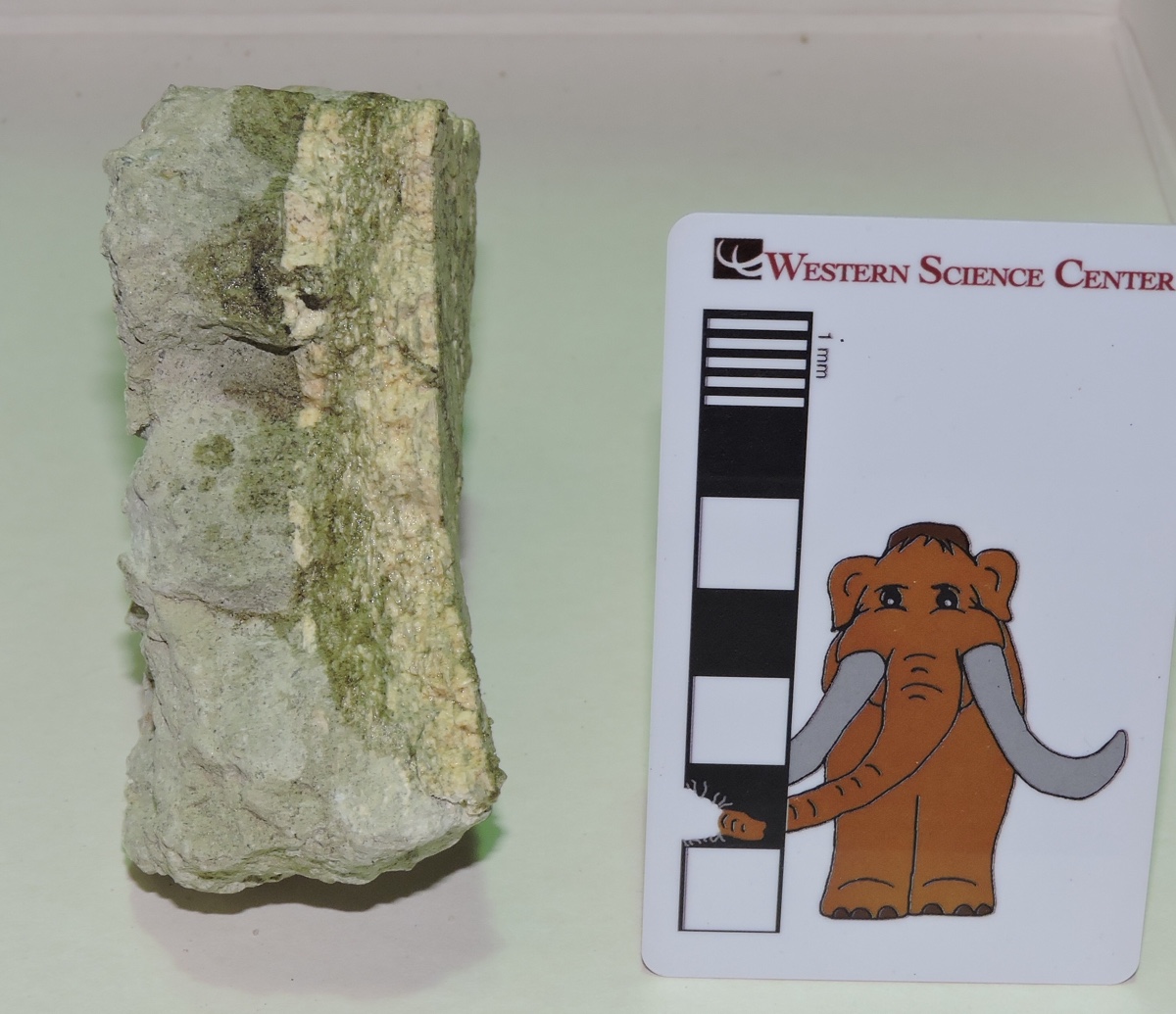

Every day on my way to work, I drive past a farm that among its denizens counts several camels. Apart from the fun of seeing these large, strange mammals, they also serve as a reminder that wild camels once roamed across North America, until their extinction around 12,000 years ago. Although today, wild camels and their relatives are found in Asia, Africa, and South America, in a bit of evolutionary irony, camels actually originated in North America and spread around the world from there. The first camels appeared around 35 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch, in the form of small fast-running herbivores like Poebrotherium. By the Miocene Epoch, camels had diversified and grown larger. This image shows one of the upper left cheek teeth of a camel that lived here in California between 18 and 14 million years ago. This tooth was collected by the Western Science Center earlier this year at a fossil site in San Bernardino National Forest. It might belong to an extinct camel called Aepycamelus, which was widespread in North America during the Miocene. However, we are still studying this tooth to determine exactly what species it represents.

Every day on my way to work, I drive past a farm that among its denizens counts several camels. Apart from the fun of seeing these large, strange mammals, they also serve as a reminder that wild camels once roamed across North America, until their extinction around 12,000 years ago. Although today, wild camels and their relatives are found in Asia, Africa, and South America, in a bit of evolutionary irony, camels actually originated in North America and spread around the world from there. The first camels appeared around 35 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch, in the form of small fast-running herbivores like Poebrotherium. By the Miocene Epoch, camels had diversified and grown larger. This image shows one of the upper left cheek teeth of a camel that lived here in California between 18 and 14 million years ago. This tooth was collected by the Western Science Center earlier this year at a fossil site in San Bernardino National Forest. It might belong to an extinct camel called Aepycamelus, which was widespread in North America during the Miocene. However, we are still studying this tooth to determine exactly what species it represents. Camels kept going strong in North America up until their extinction at the end of the last Ice Age. One of the last camels in North America was the large species Camelops hesternus, which ranged across western Northern America, including California. This image shows the underside of a Camelops skull discovered at Diamond Valley Lake and which is part of the Western Science Center's collection. The teeth are highly worn, but still bear a close resemblance to the smaller Miocene tooth. Post by WSC Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Camels kept going strong in North America up until their extinction at the end of the last Ice Age. One of the last camels in North America was the large species Camelops hesternus, which ranged across western Northern America, including California. This image shows the underside of a Camelops skull discovered at Diamond Valley Lake and which is part of the Western Science Center's collection. The teeth are highly worn, but still bear a close resemblance to the smaller Miocene tooth. Post by WSC Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Fossil Friday - Invictarx zephyri

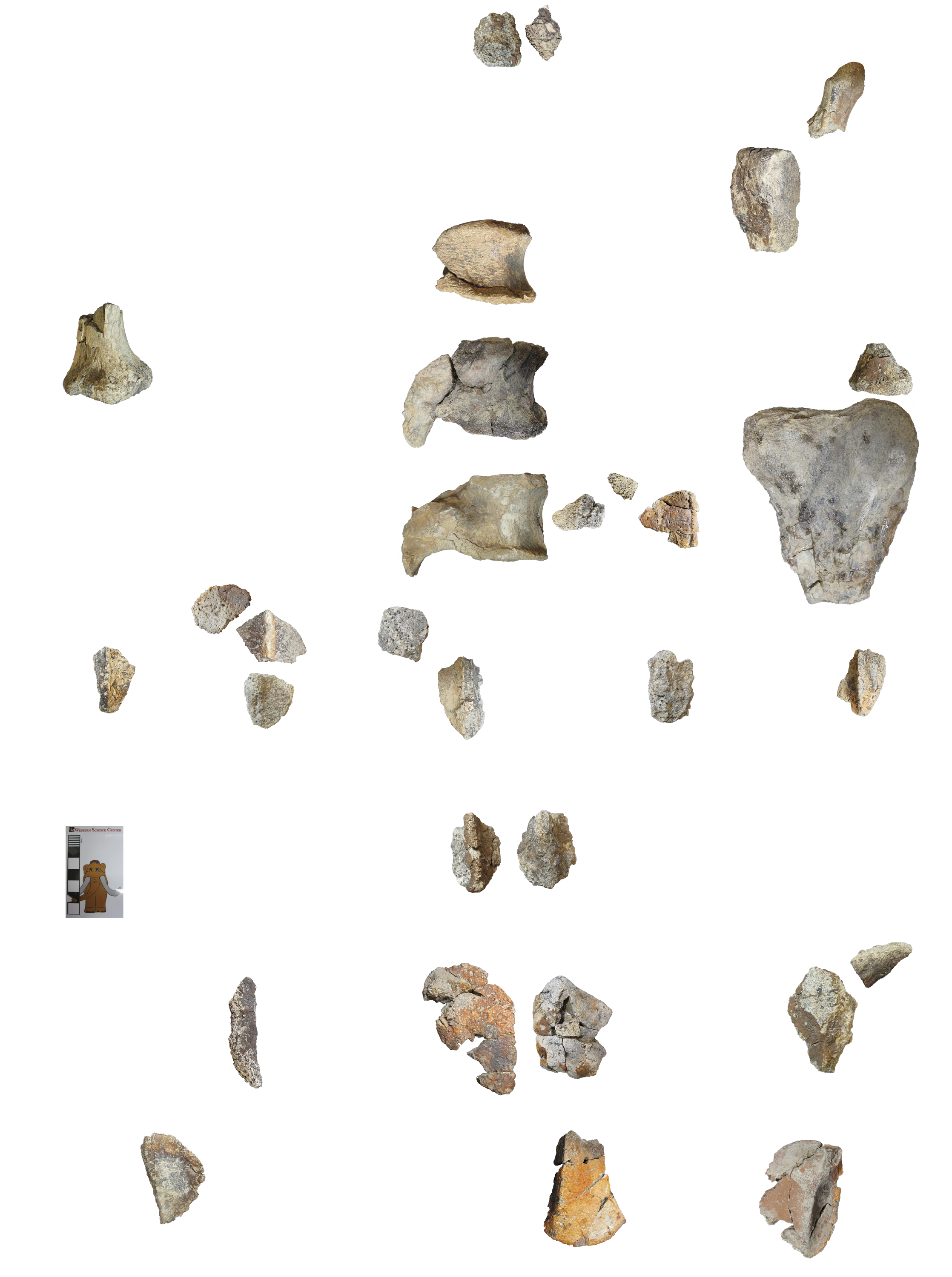

Welcome Invictarx zephyri! This is a very special Fossil Friday for me and everyone here at Western Science Center, and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. The paper naming and describing this new armored plant-eating dinosaur was published today in the online, open-access journal PeerJ. These are the fossils of Invictarx laid out, including vertebrae, parts of the forelimbs, and many osteoderms, the bony armor plates that would have been set in the animal's scaly hide - picture the armored back of an alligator. The image is a composite of three different fossil skeletons found at different spots but in the same rock layer in northwestern New Mexico, and all belonging to Invictarx zephyri.

Welcome Invictarx zephyri! This is a very special Fossil Friday for me and everyone here at Western Science Center, and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. The paper naming and describing this new armored plant-eating dinosaur was published today in the online, open-access journal PeerJ. These are the fossils of Invictarx laid out, including vertebrae, parts of the forelimbs, and many osteoderms, the bony armor plates that would have been set in the animal's scaly hide - picture the armored back of an alligator. The image is a composite of three different fossil skeletons found at different spots but in the same rock layer in northwestern New Mexico, and all belonging to Invictarx zephyri. Invictarx lived 80 million years ago, when New Mexico was covered in lush forests, dank swamps, and sluggish rivers, a far cry from the parched badlands in which my colleagues and I found the fossil remains. Invictarx is a nodosaurid, a group of armored dinosaurs that includes many species from North America and Europe. The osteoderms of Invictarx have a unique set of features that set them apart from all other nodosaurids, indicating that we have a new species on our hands, one never found by paleontologists before. Like other nodosaurids, Invictarx sported armor plates across its neck, back, and hips, which probably provided a formidable defense against predators like tyrannosaurs. We collected the first skeleton of Invictarx in 2011, at a site perched atop a high ridge whipped by 40 mile-per-hour winds, which made for a challenging excavation. With all this in mind, my sister and I took out our Latin dictionaries and came up with the name Invictarx zephyri, the "unconquerable fortress of the western wind".

Invictarx lived 80 million years ago, when New Mexico was covered in lush forests, dank swamps, and sluggish rivers, a far cry from the parched badlands in which my colleagues and I found the fossil remains. Invictarx is a nodosaurid, a group of armored dinosaurs that includes many species from North America and Europe. The osteoderms of Invictarx have a unique set of features that set them apart from all other nodosaurids, indicating that we have a new species on our hands, one never found by paleontologists before. Like other nodosaurids, Invictarx sported armor plates across its neck, back, and hips, which probably provided a formidable defense against predators like tyrannosaurs. We collected the first skeleton of Invictarx in 2011, at a site perched atop a high ridge whipped by 40 mile-per-hour winds, which made for a challenging excavation. With all this in mind, my sister and I took out our Latin dictionaries and came up with the name Invictarx zephyri, the "unconquerable fortress of the western wind". Apart from being a fascinating animal in itself, Invictarx is also the first new species of dinosaur named from the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which it was discovered. It is the first of many fossil animals and plants from the Menefee that we will describe over the coming years. Of the three specimens, we chose one to serve as the holotype of Invictarx. The holotype of an organism, living or extinct, is the specimen to which the organism's scientific name will always be attached. It serves as the standard by which all future discoveries will be assessed as to whether they represent the same species as the holotype or not. The holotype is accessioned here at the Western Science Center, and is the first holotype in our collections.

Apart from being a fascinating animal in itself, Invictarx is also the first new species of dinosaur named from the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which it was discovered. It is the first of many fossil animals and plants from the Menefee that we will describe over the coming years. Of the three specimens, we chose one to serve as the holotype of Invictarx. The holotype of an organism, living or extinct, is the specimen to which the organism's scientific name will always be attached. It serves as the standard by which all future discoveries will be assessed as to whether they represent the same species as the holotype or not. The holotype is accessioned here at the Western Science Center, and is the first holotype in our collections.  My colleagues and I return to New Mexico every summer to search for dinosaurs and other fossils in the Menefee Formation. We will very probably find additional fossils of Invictarx that will tell us more about its appearance and evolution. Naming it was really just the first step!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

My colleagues and I return to New Mexico every summer to search for dinosaurs and other fossils in the Menefee Formation. We will very probably find additional fossils of Invictarx that will tell us more about its appearance and evolution. Naming it was really just the first step!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian horn core

After a successful expedition earlier this summer, the Western Science Center crew returned to the Menefee Formation of New Mexico last week to search for more fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures that roamed the area 80 million years ago. As before, we were joined by colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, students from the University of Arizona - Tucson, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. Unlike the first trip, when we spent most of our time digging at two dinosaur quarries, this trip was mostly spent exploring for new fossil sites.This bone fragment is one of the pieces we collected while prospecting. The outer surface of this piece is riddled with deep branching grooves. This sort of texture is present only on the bony horn cores of ceratopsids, the big horned dinosaurs, such as Triceratops. When the dinosaur was alive, these grooves would have been occupied by blood vessels supplying the sheath of keratin (think fingernails) that covered the bony horn core. The photo shows the Menefee horn core fragment next to the brow horns of Ava, a horned dinosaur skull on display in WSC's "Great Wonders" exhibit. Ava's horns have the same texture.

After a successful expedition earlier this summer, the Western Science Center crew returned to the Menefee Formation of New Mexico last week to search for more fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures that roamed the area 80 million years ago. As before, we were joined by colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, students from the University of Arizona - Tucson, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. Unlike the first trip, when we spent most of our time digging at two dinosaur quarries, this trip was mostly spent exploring for new fossil sites.This bone fragment is one of the pieces we collected while prospecting. The outer surface of this piece is riddled with deep branching grooves. This sort of texture is present only on the bony horn cores of ceratopsids, the big horned dinosaurs, such as Triceratops. When the dinosaur was alive, these grooves would have been occupied by blood vessels supplying the sheath of keratin (think fingernails) that covered the bony horn core. The photo shows the Menefee horn core fragment next to the brow horns of Ava, a horned dinosaur skull on display in WSC's "Great Wonders" exhibit. Ava's horns have the same texture.  We will spend the next year preparing and studying the fossils we brought back from this summer's Menefee expeditions, and we will have much more to say about them in the very near future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

We will spend the next year preparing and studying the fossils we brought back from this summer's Menefee expeditions, and we will have much more to say about them in the very near future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - softshell turtle

Turtles have a long and amazing fossil record, appearing around 260 million years ago, even before the earliest-known dinosaurs. By the latter most part of the age of dinosaurs, the Late Cretaceous Epoch, most of the modern turtle groups had evolved. Their fossils are extremely common in rocks that represent both freshwater and marine environments.Today's Fossil Friday is a piece of turtle shell that was collected by my colleagues and I in 2017 in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. The shallow pits covering the surface suggest that it belongs to a trionychid - a softshell turtle, much like those that still live in North America today. This 80-million-year-old turtle was found at a diverse fossil site that also produced dinosaur bones, crocodile teeth, and large fish scales. These fossils were deposited in a freshwater environment, on a muddy floodplain near a slow-moving river.This is one of many turtle fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. We will have much more to say about them in the not too distant future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Turtles have a long and amazing fossil record, appearing around 260 million years ago, even before the earliest-known dinosaurs. By the latter most part of the age of dinosaurs, the Late Cretaceous Epoch, most of the modern turtle groups had evolved. Their fossils are extremely common in rocks that represent both freshwater and marine environments.Today's Fossil Friday is a piece of turtle shell that was collected by my colleagues and I in 2017 in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. The shallow pits covering the surface suggest that it belongs to a trionychid - a softshell turtle, much like those that still live in North America today. This 80-million-year-old turtle was found at a diverse fossil site that also produced dinosaur bones, crocodile teeth, and large fish scales. These fossils were deposited in a freshwater environment, on a muddy floodplain near a slow-moving river.This is one of many turtle fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. We will have much more to say about them in the not too distant future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur tibia

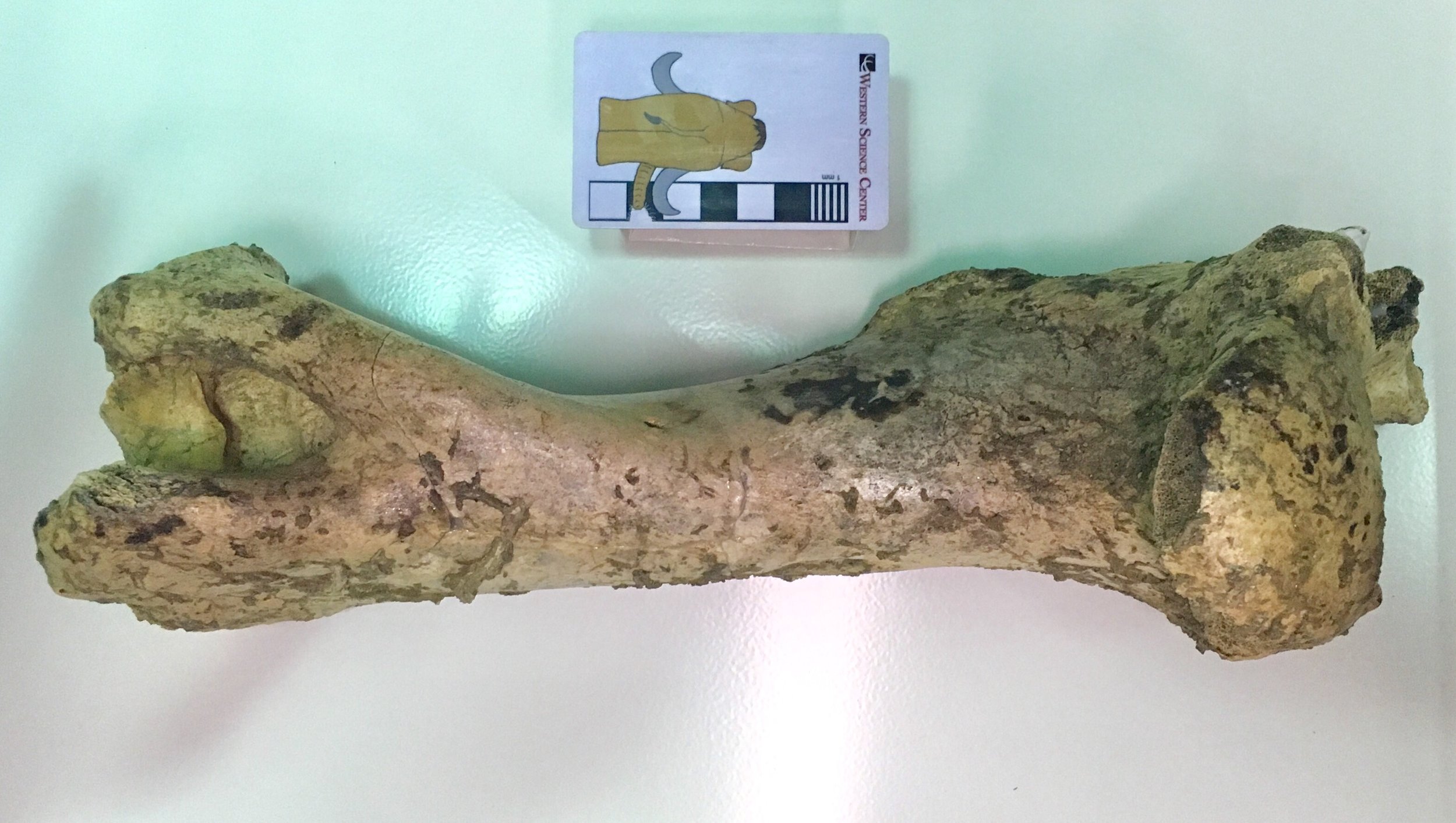

So far, most of the Late Cretaceous fossils I have shared with you for Fossil Friday have been from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and were collected over a number of years by the late Harley Garbani. The Hell Creek dates to the very end of the age of dinosaurs, just before the mass extinction 66 million years ago.There are more Hell Creek fossils at WSC to share, but today I want to showcase another fossil from a somewhat older slice of the Late Cretaceous. Last month, I showed you some plant fossils from our field area in New Mexico. Today's fossil is the tibia of a plant-eating dinosaur, probably a young hadrosaur, one of the duck-billed dinosaurs. This bone was found by University of Arizona - Tucson paleontology undergrad Kara Kelley and is now being prepared at WSC by volunteer Joe Reavis.This bone was collected from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, and is around 80 million years old. We are now preparing and studying this bone and many other fossils collected by the Western Science Center, our partners at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute of Geosciences in Springerville, AZ, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. We had a very successful expedition to the Menefee Formation in May-June; you can read an account of it written by yours truly. And we'll undertake another round of field work in the Menefee in August!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

So far, most of the Late Cretaceous fossils I have shared with you for Fossil Friday have been from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and were collected over a number of years by the late Harley Garbani. The Hell Creek dates to the very end of the age of dinosaurs, just before the mass extinction 66 million years ago.There are more Hell Creek fossils at WSC to share, but today I want to showcase another fossil from a somewhat older slice of the Late Cretaceous. Last month, I showed you some plant fossils from our field area in New Mexico. Today's fossil is the tibia of a plant-eating dinosaur, probably a young hadrosaur, one of the duck-billed dinosaurs. This bone was found by University of Arizona - Tucson paleontology undergrad Kara Kelley and is now being prepared at WSC by volunteer Joe Reavis.This bone was collected from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, and is around 80 million years old. We are now preparing and studying this bone and many other fossils collected by the Western Science Center, our partners at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute of Geosciences in Springerville, AZ, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. We had a very successful expedition to the Menefee Formation in May-June; you can read an account of it written by yours truly. And we'll undertake another round of field work in the Menefee in August!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Coelacanth fossil

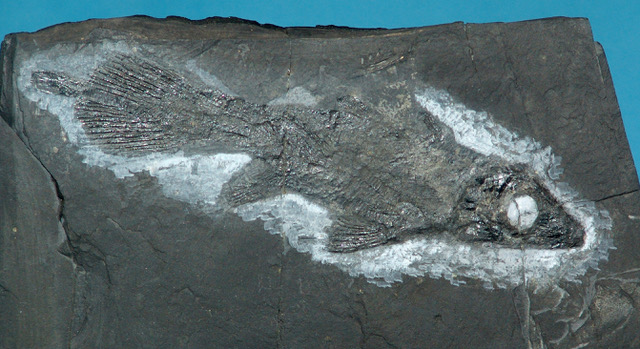

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Palm Frond

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Triceratops Teeth

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Palm Leaf

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - vacation!

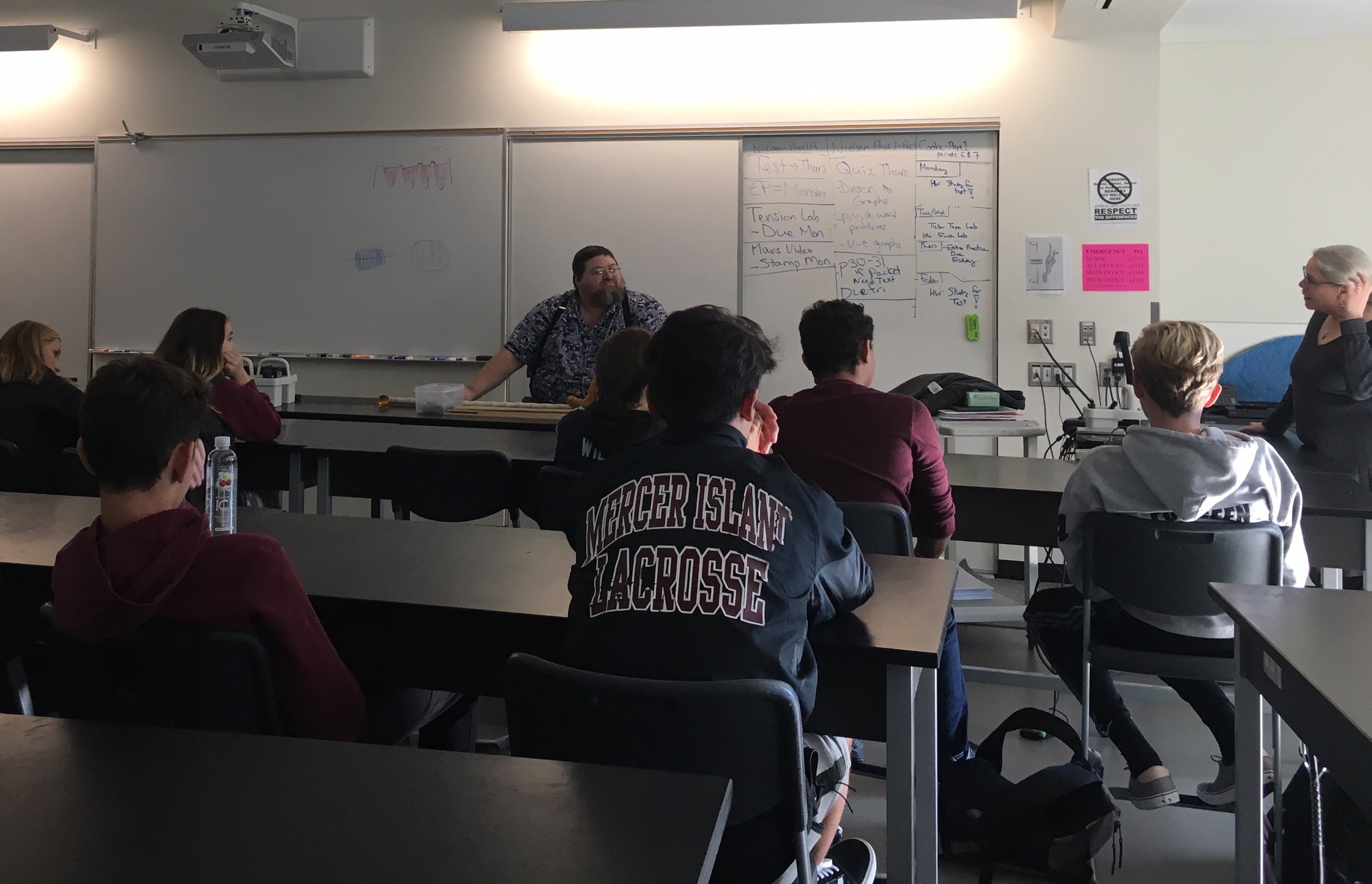

For the past week Brett and I have been in Seattle attending the 2017 meeting of the Geological Society of America, where we were presenting on the “Stepping out of the Past” and “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits. The meeting ended Wednesday night, and we’re now taking a short vacation to see geological sites in the northwest. But today things took a slight detour. While at the conference, we ran into an old friend, Patty Weston. Patty, Brett, and I were all geology majors together at Carleton College, but I had last seen her when Brett and I got married 23 years ago (although we still corresponding Facebook). She now teaches science at Mercer Island High School outside Seattle. One evening at the conference as we were discussing plans we realized that today on our way to some geological sites we would be driving within a few minutes of her school, so she invited us to stop by and talk to her class about mastodons. We said we’d love to, but since we were on vacation I didn’t have any of the cast teeth or other props I’d usually use to give such a talk. Then it occurred to me: during the “Valley of the Mastodons” Symposium Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Laboratory scanned a bunch of our mastodon teeth. So I showed Patty the files and told her that, if the school has access to a 3D printer, they could print one of the teeth and I could talk about that on Friday. And so it happened that this morning I was talked to a group of 9th graders in Washington about a tooth from my museum in California, using a 3D file produced by a lab in Virginia and printed out 12 hours earlier.

For the past week Brett and I have been in Seattle attending the 2017 meeting of the Geological Society of America, where we were presenting on the “Stepping out of the Past” and “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits. The meeting ended Wednesday night, and we’re now taking a short vacation to see geological sites in the northwest. But today things took a slight detour. While at the conference, we ran into an old friend, Patty Weston. Patty, Brett, and I were all geology majors together at Carleton College, but I had last seen her when Brett and I got married 23 years ago (although we still corresponding Facebook). She now teaches science at Mercer Island High School outside Seattle. One evening at the conference as we were discussing plans we realized that today on our way to some geological sites we would be driving within a few minutes of her school, so she invited us to stop by and talk to her class about mastodons. We said we’d love to, but since we were on vacation I didn’t have any of the cast teeth or other props I’d usually use to give such a talk. Then it occurred to me: during the “Valley of the Mastodons” Symposium Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Laboratory scanned a bunch of our mastodon teeth. So I showed Patty the files and told her that, if the school has access to a 3D printer, they could print one of the teeth and I could talk about that on Friday. And so it happened that this morning I was talked to a group of 9th graders in Washington about a tooth from my museum in California, using a 3D file produced by a lab in Virginia and printed out 12 hours earlier.

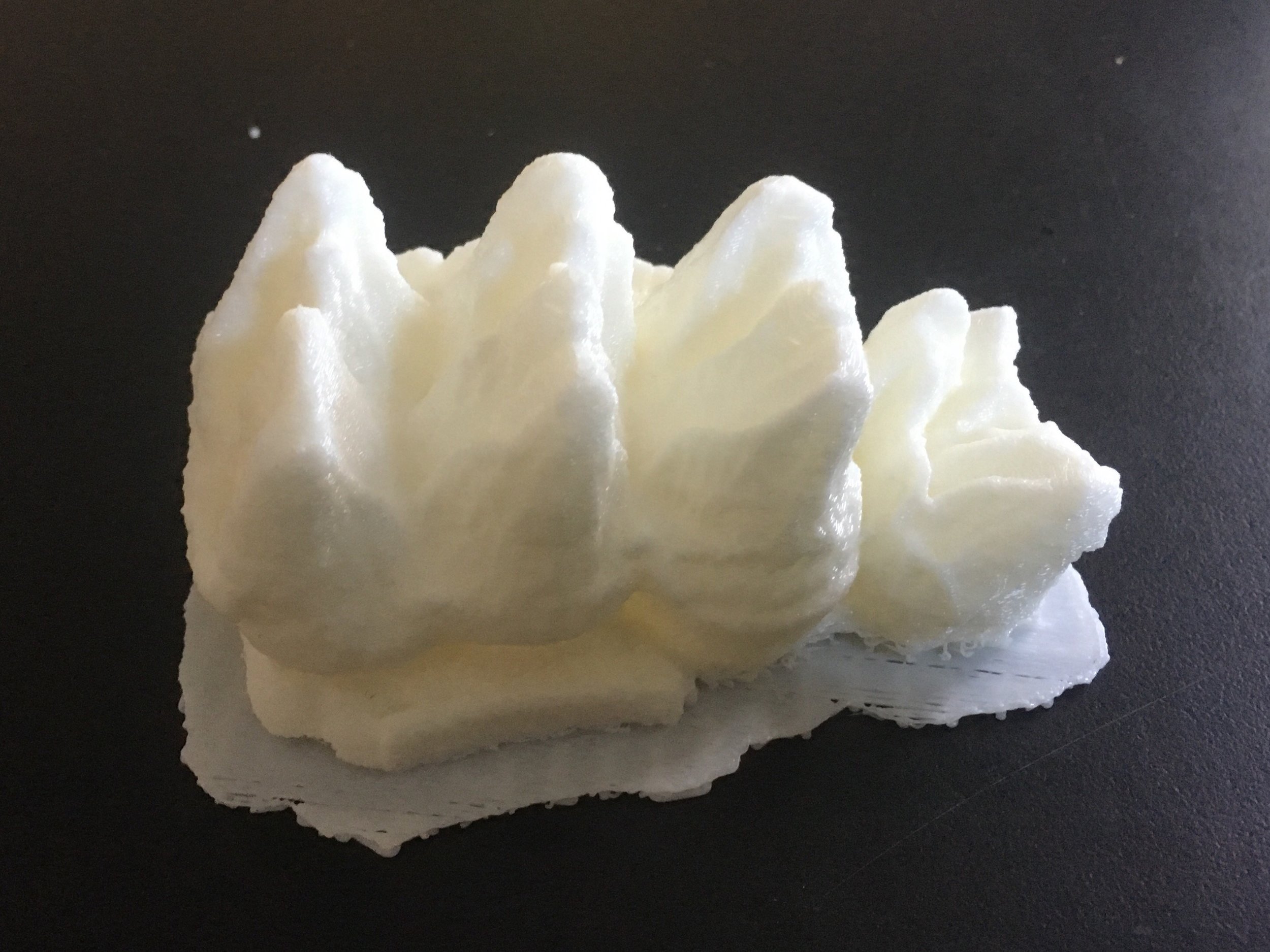

The tooth they printed, seen at the top and below, with Max, is an unerupted upper 4th premolar and the posterior part of the 3rd premolar from Diamond Valley Lake. This is the youngest mastodon (in terms of the animal’s age at death) in the WSC collection; we estimate it was between 2 and 6 months old when it died. The original specimen is currently on display in the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibit.

The tooth they printed, seen at the top and below, with Max, is an unerupted upper 4th premolar and the posterior part of the 3rd premolar from Diamond Valley Lake. This is the youngest mastodon (in terms of the animal’s age at death) in the WSC collection; we estimate it was between 2 and 6 months old when it died. The original specimen is currently on display in the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibit. In the last 2 months WSC has jumped into 3D technology in a big way, recently installing our first printer and with more equipment to come. Today’s visit really made clearer to me the power this technology offers. Thanks to Patty Weston and Mercer Island High School for making this happen, and of course to Bernard and our Science Under the Stars donors who have made this available to WSC.

In the last 2 months WSC has jumped into 3D technology in a big way, recently installing our first printer and with more equipment to come. Today’s visit really made clearer to me the power this technology offers. Thanks to Patty Weston and Mercer Island High School for making this happen, and of course to Bernard and our Science Under the Stars donors who have made this available to WSC.

Fossil Friday - Bison humerus

This rather stout bone is one of our best-preserved bison humeri. This is the left humerus, shown above in anterior view. The distal end, at the elbow joint, is on the left, while the proximal end (shoulder joint) is on the right. Bison have a large knob of bone called the lateral tuberosity which is broken off of this specimen; it should be at located at the lower right. The darker lines and patches are sediment that has not yet been removed. Below is the posterior view:

This rather stout bone is one of our best-preserved bison humeri. This is the left humerus, shown above in anterior view. The distal end, at the elbow joint, is on the left, while the proximal end (shoulder joint) is on the right. Bison have a large knob of bone called the lateral tuberosity which is broken off of this specimen; it should be at located at the lower right. The darker lines and patches are sediment that has not yet been removed. Below is the posterior view: Again, proximal is on the right. The large humoral head that articulates with the scapula to form the shoulder joint is visible on the right. The large notch on the distal end (on the left) is the olecranon fossa. This accommodates the olecranon process of the ulna (the point of the elbow) when the front leg is extended.Here are the lateral and medial views:

Again, proximal is on the right. The large humoral head that articulates with the scapula to form the shoulder joint is visible on the right. The large notch on the distal end (on the left) is the olecranon fossa. This accommodates the olecranon process of the ulna (the point of the elbow) when the front leg is extended.Here are the lateral and medial views:

Damage is visible at the proximal end in these views, where the lateral tuberosity was originally located. This humerus was found at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. West Dam deposits are older than those at the East Dam, and contain both Bison antiquus and Bison latifrons; it's not clear which species is represented here.

Damage is visible at the proximal end in these views, where the lateral tuberosity was originally located. This humerus was found at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. West Dam deposits are older than those at the East Dam, and contain both Bison antiquus and Bison latifrons; it's not clear which species is represented here.

Fossil Friday - Annularia

I've spent the last week trying to catch up on administrative work while pouring over all the data we gathered during our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" road trip. But after several weeks of almost all mastodons it gives me the chance to feature a different organism for Fossil Friday. The specimen shown above was donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham College Geology Department, and comes from the famous Carboniferous Period deposits at Mazon Creek in Illinois. While this looks somewhat like a flower, it's actually a whorl of leaves known as Annularia (flowers had not yet evolved in the Carboniferous). Annularia are the leaves of horsetails or scouring rushes, a plant that's still around as the genus Equisetum:

I've spent the last week trying to catch up on administrative work while pouring over all the data we gathered during our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" road trip. But after several weeks of almost all mastodons it gives me the chance to feature a different organism for Fossil Friday. The specimen shown above was donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham College Geology Department, and comes from the famous Carboniferous Period deposits at Mazon Creek in Illinois. While this looks somewhat like a flower, it's actually a whorl of leaves known as Annularia (flowers had not yet evolved in the Carboniferous). Annularia are the leaves of horsetails or scouring rushes, a plant that's still around as the genus Equisetum:

Modern horsetails are small, spore-bearing plants that live primarily in marshy areas. But in the Carboniferous there were giant horsetails that grew to be up to 10 meters tall, and were among the world's most common trees.The name Annularia illustrates a particular difficulty faced by paleobotanists. If you're trying to identify a fossil vertebrate, you face several difficulties related to variability. Bones from different parts of the body look different, and they also vary with age (ontogenetic variation) and sex (sexual dimorphism). Plants present all these same issues, but they may also only grow some structures at certain times of the year (flowers, seeds, spores, pollen), the body parts may easily or even intentionally separate from the rest of the plant (deciduous leaves, seeds, spores, pollen), and preservation potential may be wildly different from one part to another. The result is that, if you have a bunch of fossil leaves and fossil stems, it's often very difficult to tell which ones go together unless that happen to be preserved actually connected to one another. Paleobotanists get around this problem by naming form taxa or organ taxa. The name Annularia specifically refers to leaf whorls of horsetails that share a particular morphology. Other parts of the plant, such as the stems and the spore cones, have different names. Fossil horsetails are quite common and well-known in Carboniferous rocks, so we actually know that fossil stems called Calamites come from the same plants that produce Annularia.

Modern horsetails are small, spore-bearing plants that live primarily in marshy areas. But in the Carboniferous there were giant horsetails that grew to be up to 10 meters tall, and were among the world's most common trees.The name Annularia illustrates a particular difficulty faced by paleobotanists. If you're trying to identify a fossil vertebrate, you face several difficulties related to variability. Bones from different parts of the body look different, and they also vary with age (ontogenetic variation) and sex (sexual dimorphism). Plants present all these same issues, but they may also only grow some structures at certain times of the year (flowers, seeds, spores, pollen), the body parts may easily or even intentionally separate from the rest of the plant (deciduous leaves, seeds, spores, pollen), and preservation potential may be wildly different from one part to another. The result is that, if you have a bunch of fossil leaves and fossil stems, it's often very difficult to tell which ones go together unless that happen to be preserved actually connected to one another. Paleobotanists get around this problem by naming form taxa or organ taxa. The name Annularia specifically refers to leaf whorls of horsetails that share a particular morphology. Other parts of the plant, such as the stems and the spore cones, have different names. Fossil horsetails are quite common and well-known in Carboniferous rocks, so we actually know that fossil stems called Calamites come from the same plants that produce Annularia.

Fossil Friday - mastodon thoracic vertebra

As I'm in the middle of our Mastodons of Unusual Size data-collecting trip, my Fossil Friday post will have to be a short one. But, in keeping with our road trip topic, it will of course feature a mastodon!The specimen shown above is an anterior thoracic vertebra, shown in anterior view. The image is turned sideways to fit better on the screen, so the bottom of the vertebra is on the left. The bone is still in its field jacket, and has only been partially prepared.Thoracic vertebra in mammals are the ones that articulate with the ribs, and the articulations are visible on the ends of the processes projecting from each side of the vertebra. The tall neural spine extends from the top of the vertebra (right in the photo). The neural spines serve in part as muscle attachment points for muscles that hold up the head and help support the front legs. In quadrupedal animals with large, heavy heads, such as mastodons, the anterior neural spines are very long, providing more surface area and better leverage for those muscles.This vertebra was collected from the Diamond Valley Lake East Dam, close to where the Western Science Center is now located.

As I'm in the middle of our Mastodons of Unusual Size data-collecting trip, my Fossil Friday post will have to be a short one. But, in keeping with our road trip topic, it will of course feature a mastodon!The specimen shown above is an anterior thoracic vertebra, shown in anterior view. The image is turned sideways to fit better on the screen, so the bottom of the vertebra is on the left. The bone is still in its field jacket, and has only been partially prepared.Thoracic vertebra in mammals are the ones that articulate with the ribs, and the articulations are visible on the ends of the processes projecting from each side of the vertebra. The tall neural spine extends from the top of the vertebra (right in the photo). The neural spines serve in part as muscle attachment points for muscles that hold up the head and help support the front legs. In quadrupedal animals with large, heavy heads, such as mastodons, the anterior neural spines are very long, providing more surface area and better leverage for those muscles.This vertebra was collected from the Diamond Valley Lake East Dam, close to where the Western Science Center is now located.

Fossil Friday - giant tortoise shell fragment

When visitors get "behind the scene" tours of fossil repositories, they are often surprised at the spectacularly unimpressive appearance of some of the fossils. A lot of preserved fossil specimens may not be especially attractive to look at, but they can still provide important scientific information about particular anatomical features, the amount of variation present, or the presence of a particular organism in an ecosystem. The nondescript bone shown above is from the Southern California Edison El Casco Substation in northern Riverside County. The light grey areas are sediment still adhering to the bone. The preserved fragment is broad and flat, and because it's broken we can see the cross section:

When visitors get "behind the scene" tours of fossil repositories, they are often surprised at the spectacularly unimpressive appearance of some of the fossils. A lot of preserved fossil specimens may not be especially attractive to look at, but they can still provide important scientific information about particular anatomical features, the amount of variation present, or the presence of a particular organism in an ecosystem. The nondescript bone shown above is from the Southern California Edison El Casco Substation in northern Riverside County. The light grey areas are sediment still adhering to the bone. The preserved fragment is broad and flat, and because it's broken we can see the cross section: Both surfaces are composed of very thick layers of dense cortical bone, with spongy bone sandwiched between them. This internal structure in a broad, flat bone in commonly seen in turtle shells.What's remarkable is that this shell fragment is almost 2 cm thick. The only land turtle known from North America in the Pleistocene with such a massive shell is the extinct giant tortoise Hesperotestudo. Hesperotestudo is an extinct genus related to the modern gopher tortoise, but in terms of size it was more similar to the living giant tortoises of the genus Geochelone:

Both surfaces are composed of very thick layers of dense cortical bone, with spongy bone sandwiched between them. This internal structure in a broad, flat bone in commonly seen in turtle shells.What's remarkable is that this shell fragment is almost 2 cm thick. The only land turtle known from North America in the Pleistocene with such a massive shell is the extinct giant tortoise Hesperotestudo. Hesperotestudo is an extinct genus related to the modern gopher tortoise, but in terms of size it was more similar to the living giant tortoises of the genus Geochelone: There were a handful of bones from the El Casco Substation that were tentatively referred to Hesperotestudo. While none of the specimens are visually stunning, they establish the presence of giant tortoises in Riverside County during the Ice Age.

There were a handful of bones from the El Casco Substation that were tentatively referred to Hesperotestudo. While none of the specimens are visually stunning, they establish the presence of giant tortoises in Riverside County during the Ice Age.

First day

Today was my first official day as director of the Western Science Center. As with most new jobs, the first day was somewhat hectic, and mostly filled with paperwork.In addition to the usual tax and payroll-related paperwork, starting a new job in an academic institution like a museum also means setting up computer access and email accounts. In my case, it also means reviewing lots of museum policy documents, such as collections and ethics policies, board procedures, and budget sheets.I did get out of my office for awhile, though, for a last look at the Beatles exhibit (the exhibit closed yesterday, but we've only just started to remove it). I also took time to get to know some of the staff, and to look at some of the lab facilities. And, of course, I couldn't let my first day in the Valley of the Mastodons pass without looking at some mastodon remains:

Today was my first official day as director of the Western Science Center. As with most new jobs, the first day was somewhat hectic, and mostly filled with paperwork.In addition to the usual tax and payroll-related paperwork, starting a new job in an academic institution like a museum also means setting up computer access and email accounts. In my case, it also means reviewing lots of museum policy documents, such as collections and ethics policies, board procedures, and budget sheets.I did get out of my office for awhile, though, for a last look at the Beatles exhibit (the exhibit closed yesterday, but we've only just started to remove it). I also took time to get to know some of the staff, and to look at some of the lab facilities. And, of course, I couldn't let my first day in the Valley of the Mastodons pass without looking at some mastodon remains:

Headed west

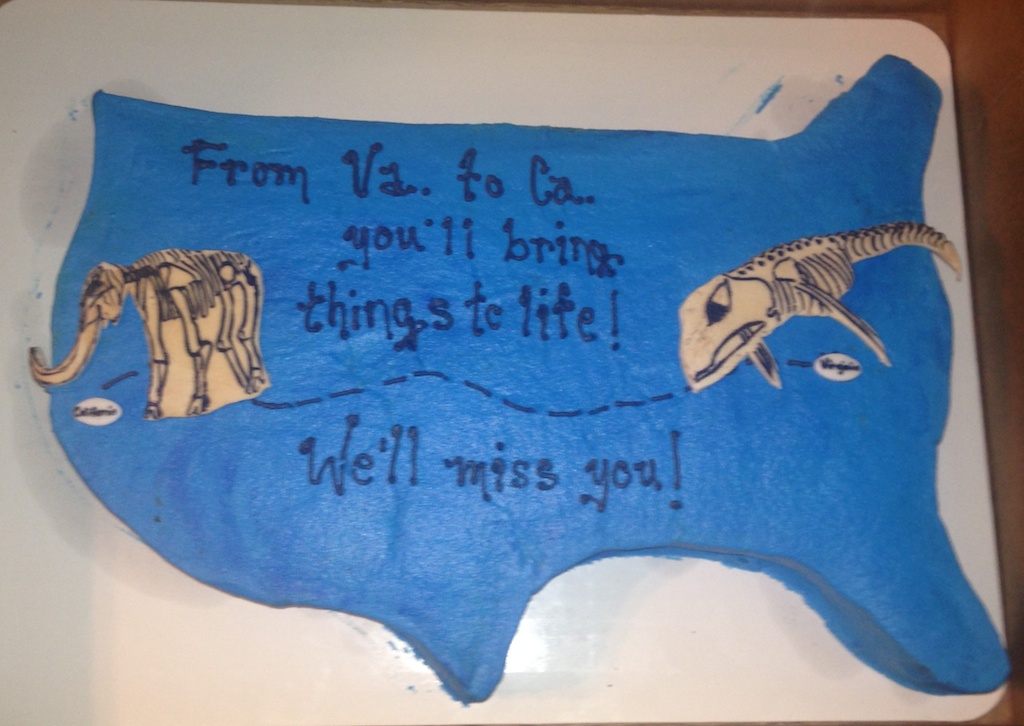

For those of you that haven't been following me online (and hoping those who have will bear with me), I'd like to introduce myself. My name is Alton Dooley, and I'm a "museum person", a catch-all phrase for folks who have immersed themselves in various aspects of museum operations. I'm a paleontologist and geologist by training, but I've been working with and for museums for my entire adult life. Tomorrow, I begin driving west from Virginia to California to begin my new job as Executive Director of the Western Science Center.

For those of you that haven't been following me online (and hoping those who have will bear with me), I'd like to introduce myself. My name is Alton Dooley, and I'm a "museum person", a catch-all phrase for folks who have immersed themselves in various aspects of museum operations. I'm a paleontologist and geologist by training, but I've been working with and for museums for my entire adult life. Tomorrow, I begin driving west from Virginia to California to begin my new job as Executive Director of the Western Science Center. For the last 15 years I've worked for the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville, Virginia (above). I initially worked for VMNH as an intern while I was still an undergraduate in the late 1980s, and in 1999, after completing my PhD, I was hired there as the Laboratory Manager for Paleontology and Earth Sciences. After several years I was promoted to Assistant Curator, and eventually became Curator of Paleontology, in charge of all of VMNH's fossil collections and paleontology-related activities.Even though I loved my job at VMNH, new opportunities have presented themselves on occasion, and when the Western Science Center offered me the position of director it was too good to pass up. And so I've spent the last month packing, getting my affairs at VMNH in order to ensure a smooth transition, and saying goodbye to coworkers, friends, and family:

For the last 15 years I've worked for the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville, Virginia (above). I initially worked for VMNH as an intern while I was still an undergraduate in the late 1980s, and in 1999, after completing my PhD, I was hired there as the Laboratory Manager for Paleontology and Earth Sciences. After several years I was promoted to Assistant Curator, and eventually became Curator of Paleontology, in charge of all of VMNH's fossil collections and paleontology-related activities.Even though I loved my job at VMNH, new opportunities have presented themselves on occasion, and when the Western Science Center offered me the position of director it was too good to pass up. And so I've spent the last month packing, getting my affairs at VMNH in order to ensure a smooth transition, and saying goodbye to coworkers, friends, and family: I'll be spending the next couple of weeks driving across the country and taking care of the myriad chores involved with relocating before I officially start in my new position. Which brings me to this blog...In September 2007 I began a blog called "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" to describe and promote the activities of my department at VMNH. Much to my surprise the blog was reasonably successful, and after 7 years and with 680 published posts "Updates" is one of the longest-running geoscience blogs in the world.While "Updates" was my creation, it is deeply intertwined with VMNH and so I decided not to try and adapt it to a new function. (Christina Byrd, the paleontology technician at VMNH, is going to continue writing posts for "Updates" so if you're a regular reader, have no fear!) Instead I decided to start a new blog with the Western Science Center specifically in mind.WSC is located near Diamond Valley, which is sometimes informally referred to as Valley of the Mastodons because of the large number of mastodon remains recovered there during the construction of the Diamond Valley Lake Reservoir. Those specimens are now housed at WSC, so "Valley of the Mastodon" seems a fitting name for this blog.I envision a variety of functions for "Valley of the Mastodon". In part I'll be announcing WSC events, new exhibits, guest speakers, etc. But I expect there will be an emphasis on the WSC collections, and on regional geology and paleontology. I spent a lot of my time at VMNH learning about the state's geology and paleontology, and really enjoyed sharing my discoveries on "Updates". So far I've spent a total of about 14 days in California, spread across 9 different cities. For me, California represents a whole new state to discover, and I hope to share what I learn with you on these pages.

I'll be spending the next couple of weeks driving across the country and taking care of the myriad chores involved with relocating before I officially start in my new position. Which brings me to this blog...In September 2007 I began a blog called "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" to describe and promote the activities of my department at VMNH. Much to my surprise the blog was reasonably successful, and after 7 years and with 680 published posts "Updates" is one of the longest-running geoscience blogs in the world.While "Updates" was my creation, it is deeply intertwined with VMNH and so I decided not to try and adapt it to a new function. (Christina Byrd, the paleontology technician at VMNH, is going to continue writing posts for "Updates" so if you're a regular reader, have no fear!) Instead I decided to start a new blog with the Western Science Center specifically in mind.WSC is located near Diamond Valley, which is sometimes informally referred to as Valley of the Mastodons because of the large number of mastodon remains recovered there during the construction of the Diamond Valley Lake Reservoir. Those specimens are now housed at WSC, so "Valley of the Mastodon" seems a fitting name for this blog.I envision a variety of functions for "Valley of the Mastodon". In part I'll be announcing WSC events, new exhibits, guest speakers, etc. But I expect there will be an emphasis on the WSC collections, and on regional geology and paleontology. I spent a lot of my time at VMNH learning about the state's geology and paleontology, and really enjoyed sharing my discoveries on "Updates". So far I've spent a total of about 14 days in California, spread across 9 different cities. For me, California represents a whole new state to discover, and I hope to share what I learn with you on these pages.