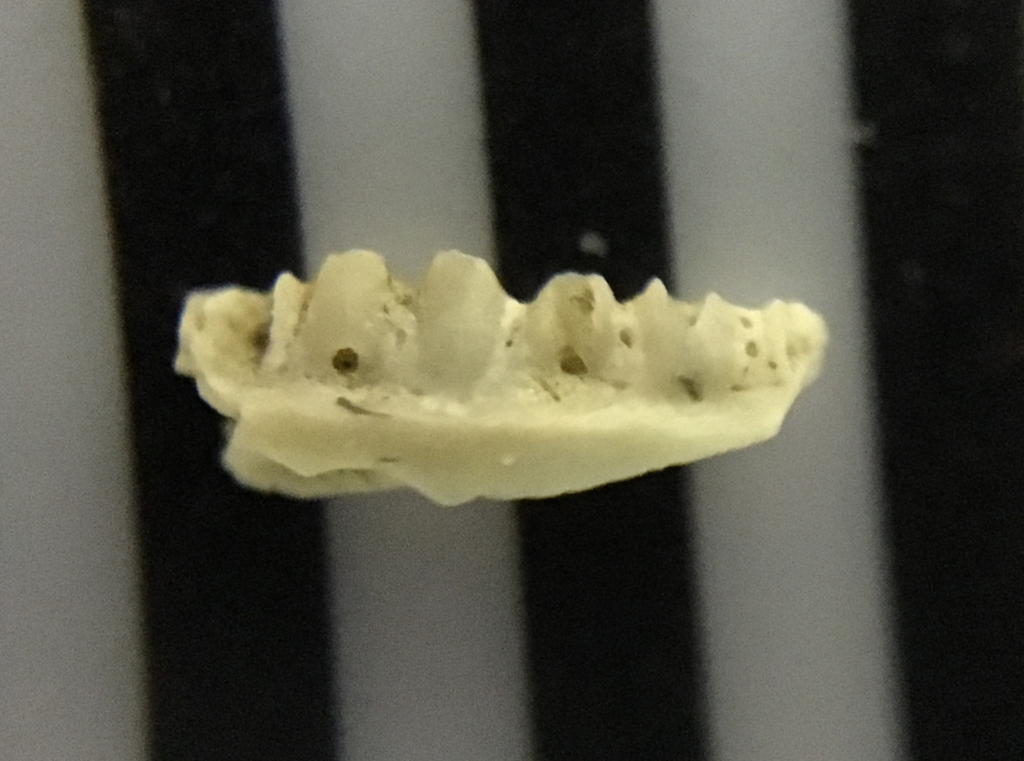

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view:

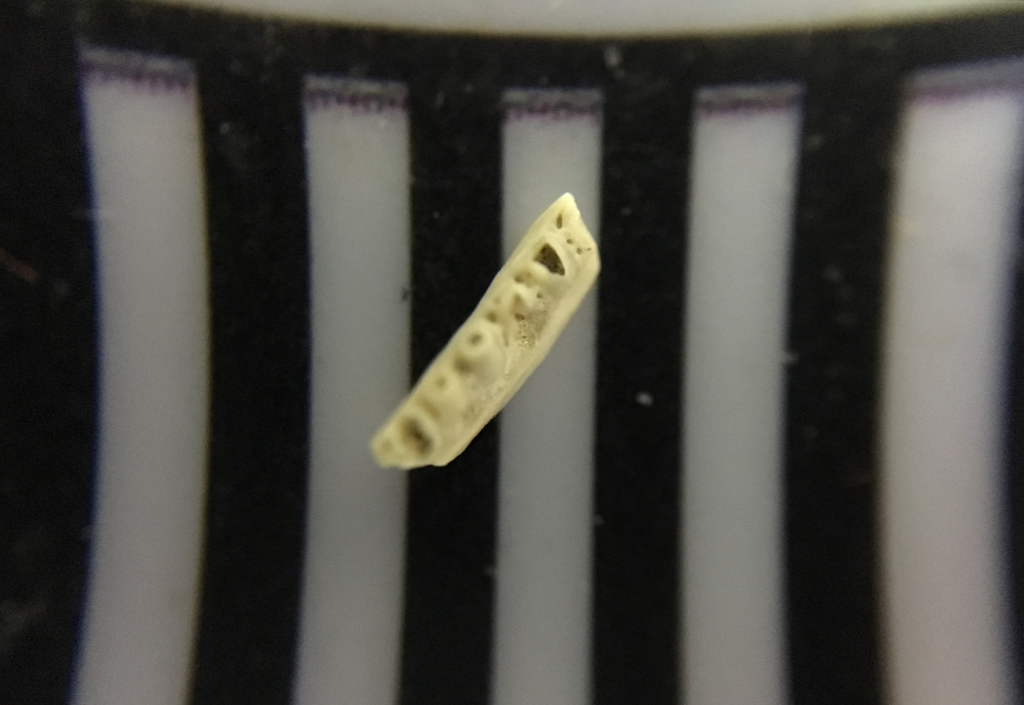

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view: In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera):

In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera): Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects):

Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects): Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.