This post was originally published on my old VMNH blog, "Updates from the Paleontology Lab", on March 8, 2010. The post includes anatomical observations that are relevant to human evolution; WSC's exhibit on human origins, "Stepping Out of the Past", is open until May 21.Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America Northeastern/Southeastern Section meeting, and I’ll be posting daily updates on that conference. Prior to leaving for the conference, I’ll be taking most of this week off. I thought an explanation for my absence is justified, especially as it involves some interesting information about mammal teeth.Nearly all mammals are strongly heterodont, meaning that they have different types of teeth in their mouths. Mammal teeth are typically divided into four groups. From the front of the mouth to the back, these are the incisors, canines, premolars, and molars, respectively abbreviated I, C, P, and M in the upper jaw, and i, c, p, and m in the lower jaw. So, for example, the second upper molar would be M2, while the second lower molar would be m2. Most mammals also have a temporary set of teeth, called milk or deciduous teeth, abbreviated with a “d” prefix (dp1 is the first lower deciduous premolar). Incidentally, some of the terms are different for humans; canines are referred to as eye teeth, premolars as bicuspids, second molars as 12-year teeth, and third molars as wisdom teeth. For some reason, there’s also a convention in humans to refer to the post-canine deciduous teeth as molars rather than as premolars. I’m not sure why this is done, except that these teeth are similar in shape to the permanent molars. They are replaced by the premolars, however, not the molars. Are there any developmental folks out there that can shed some light on this?Anyway, it turns out that tooth counts are pretty significant for determining relationships among different groups of mammals, so there’s also a notation for overall dental formulas. For example:

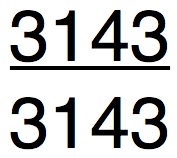

This post was originally published on my old VMNH blog, "Updates from the Paleontology Lab", on March 8, 2010. The post includes anatomical observations that are relevant to human evolution; WSC's exhibit on human origins, "Stepping Out of the Past", is open until May 21.Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America Northeastern/Southeastern Section meeting, and I’ll be posting daily updates on that conference. Prior to leaving for the conference, I’ll be taking most of this week off. I thought an explanation for my absence is justified, especially as it involves some interesting information about mammal teeth.Nearly all mammals are strongly heterodont, meaning that they have different types of teeth in their mouths. Mammal teeth are typically divided into four groups. From the front of the mouth to the back, these are the incisors, canines, premolars, and molars, respectively abbreviated I, C, P, and M in the upper jaw, and i, c, p, and m in the lower jaw. So, for example, the second upper molar would be M2, while the second lower molar would be m2. Most mammals also have a temporary set of teeth, called milk or deciduous teeth, abbreviated with a “d” prefix (dp1 is the first lower deciduous premolar). Incidentally, some of the terms are different for humans; canines are referred to as eye teeth, premolars as bicuspids, second molars as 12-year teeth, and third molars as wisdom teeth. For some reason, there’s also a convention in humans to refer to the post-canine deciduous teeth as molars rather than as premolars. I’m not sure why this is done, except that these teeth are similar in shape to the permanent molars. They are replaced by the premolars, however, not the molars. Are there any developmental folks out there that can shed some light on this?Anyway, it turns out that tooth counts are pretty significant for determining relationships among different groups of mammals, so there’s also a notation for overall dental formulas. For example: means 3 incisors, 1 canine, 4 premolars, and 3 molars in each half of the upper jaw, and the same count in each half of the lower jaw. This gives a total of 44 teeth in the mouth. This is the primitive tooth count for most placental mammal groups, but most groups have modified this number in the course of their evolution.One of the major divisions in the Order Primates is based largely on tooth counts. The Platyrrhini, or New World monkeys, have a tooth count of:

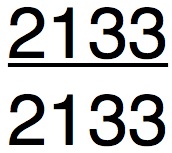

means 3 incisors, 1 canine, 4 premolars, and 3 molars in each half of the upper jaw, and the same count in each half of the lower jaw. This gives a total of 44 teeth in the mouth. This is the primitive tooth count for most placental mammal groups, but most groups have modified this number in the course of their evolution.One of the major divisions in the Order Primates is based largely on tooth counts. The Platyrrhini, or New World monkeys, have a tooth count of: while the Catarrhini, or Old World monkeys, gibbons, and apes, have a count of:

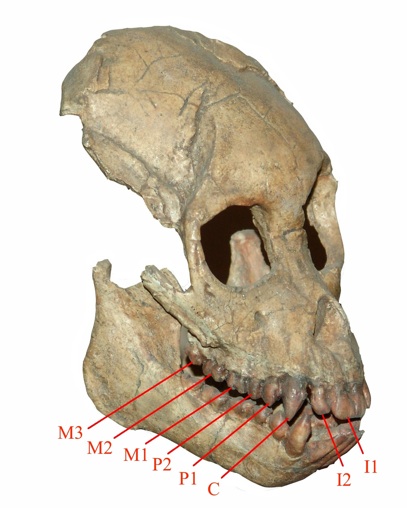

while the Catarrhini, or Old World monkeys, gibbons, and apes, have a count of: All the catarrhines share this count, going back to the Late Eocene or Early Oligocene. Here’s the Early Miocene Proconsul (specimen from AMNH):

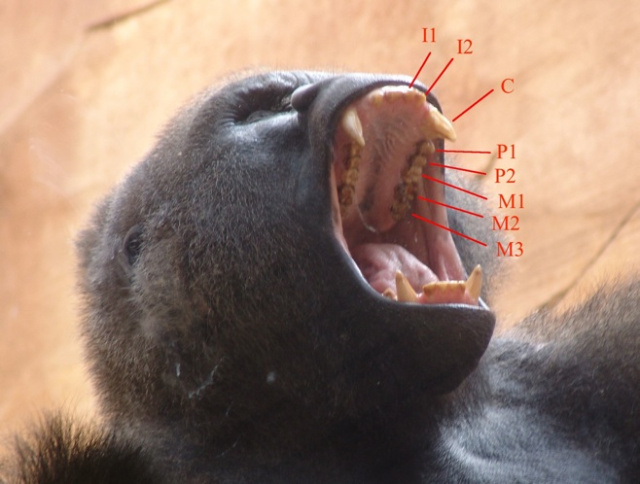

All the catarrhines share this count, going back to the Late Eocene or Early Oligocene. Here’s the Early Miocene Proconsul (specimen from AMNH): And here’s a modern Gorilla (photo taken at the Henry Doorly Zoo):

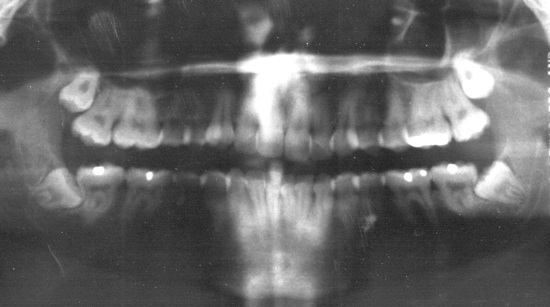

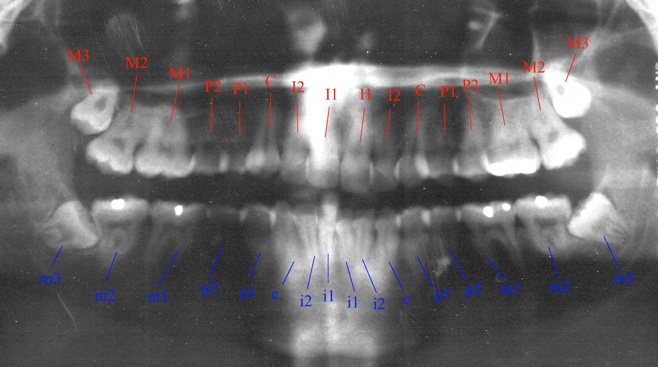

And here’s a modern Gorilla (photo taken at the Henry Doorly Zoo): Humans, as catorrhines, have the same tooth count, as is apparent in Brett’s dental X-rays:

Humans, as catorrhines, have the same tooth count, as is apparent in Brett’s dental X-rays: Notice, however, the unusual position of the upper and lower third molars (M3 and m3). These are the wisdom teeth, and as is commonly the case in humans, they are impacted (growing into the side of the adjacent teeth). Impacted wisdom teeth can cause pain and infection, and are often surgically removed. This is a relict of humans’ evolutionary history; as the only short-snouted catarrhines, there isn’t room in our mouths for the third molar. In fact, other dental abnormalities are fairly common in humans, probably due to the same developmental issues, which brings me to my absence from work later this week.These are my son Tim’s dental X-rays, taken just before his 12th birthday:

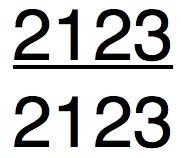

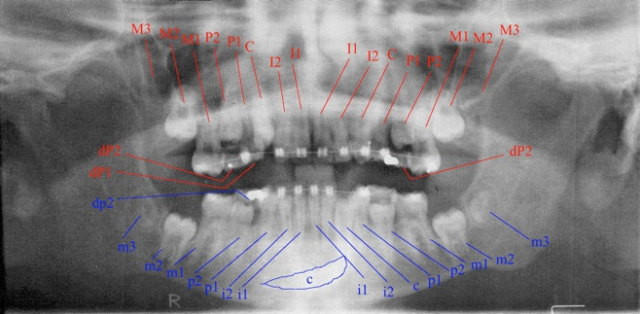

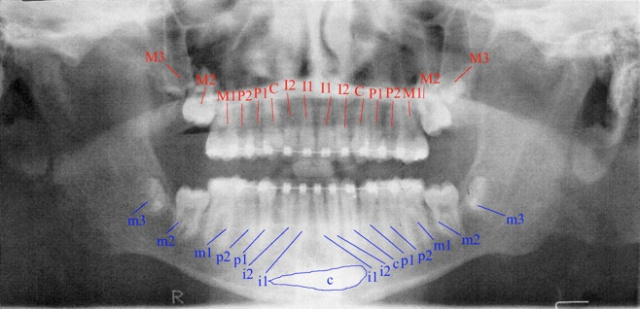

Notice, however, the unusual position of the upper and lower third molars (M3 and m3). These are the wisdom teeth, and as is commonly the case in humans, they are impacted (growing into the side of the adjacent teeth). Impacted wisdom teeth can cause pain and infection, and are often surgically removed. This is a relict of humans’ evolutionary history; as the only short-snouted catarrhines, there isn’t room in our mouths for the third molar. In fact, other dental abnormalities are fairly common in humans, probably due to the same developmental issues, which brings me to my absence from work later this week.These are my son Tim’s dental X-rays, taken just before his 12th birthday: There’s a lot going on in this image. The bright objects are braces, and two fillings. Here’s the same image, with the teeth labeled:

There’s a lot going on in this image. The bright objects are braces, and two fillings. Here’s the same image, with the teeth labeled: Note that the image is reversed (right is on the left). There are four or five deciduous teeth still in place (four are labeled), although the permanent teeth have formed beneath them. It’s also clear that the M2’s and m2’s (the 12-year teeth) have formed but not yet erupted, and the third molars are just starting to develop (left m3 seems a little further along than the others). There is a lot of crowding (human developmental issues, again!) that has prevented the canines from erupting normally, which is why the braces were needed.The big problem is in the middle of the lower jaw, that blue-outlined area labeled “c”. That’s the right lower canine, and it’s completely out of position. It has rotated almost 90 degrees, and is laying across the mandibular symphysis with its crown sitting underneath the left lower canine.Here’s a follow-up X-ray from 13 months later:

Note that the image is reversed (right is on the left). There are four or five deciduous teeth still in place (four are labeled), although the permanent teeth have formed beneath them. It’s also clear that the M2’s and m2’s (the 12-year teeth) have formed but not yet erupted, and the third molars are just starting to develop (left m3 seems a little further along than the others). There is a lot of crowding (human developmental issues, again!) that has prevented the canines from erupting normally, which is why the braces were needed.The big problem is in the middle of the lower jaw, that blue-outlined area labeled “c”. That’s the right lower canine, and it’s completely out of position. It has rotated almost 90 degrees, and is laying across the mandibular symphysis with its crown sitting underneath the left lower canine.Here’s a follow-up X-ray from 13 months later: The improvement is remarkable. The deciduous teeth are all gone, and the spacing is a little better. The third molars are more developed, but it appears they’ll be impacted and eventually need to be removed. With the extra space, three of the canines have been able to grow in normally. Unfortunately, that lower right canine has actually gotten worse. It’s now in a position where it can cause damage to the nerves and vessels supplying all the lower incisors and the other canine, and will have to be removed through fairly invasive surgery. Tim will be having that surgery this week, and I’ve decided to take off Wednesday and Thursday while he recovers.Of course, with a missing tooth Tim could eventually have occlusion problems which could cause rapid and abnormal wear on his teeth, like what happened to the Rappahannock River sperm whale (note the massive wear facets on the two teeth on the right):

The improvement is remarkable. The deciduous teeth are all gone, and the spacing is a little better. The third molars are more developed, but it appears they’ll be impacted and eventually need to be removed. With the extra space, three of the canines have been able to grow in normally. Unfortunately, that lower right canine has actually gotten worse. It’s now in a position where it can cause damage to the nerves and vessels supplying all the lower incisors and the other canine, and will have to be removed through fairly invasive surgery. Tim will be having that surgery this week, and I’ve decided to take off Wednesday and Thursday while he recovers.Of course, with a missing tooth Tim could eventually have occlusion problems which could cause rapid and abnormal wear on his teeth, like what happened to the Rappahannock River sperm whale (note the massive wear facets on the two teeth on the right): To avoid this problem, Tim’s braces have been used to open a gap between the right i2 and p1 (not visible in these photos), where the canine should be. An artificial tooth will fill this gap, to help ensure proper occlusion between his upper and lower teeth.Shortly after the original post was written, Tim successfully had the problematic canine removed.

To avoid this problem, Tim’s braces have been used to open a gap between the right i2 and p1 (not visible in these photos), where the canine should be. An artificial tooth will fill this gap, to help ensure proper occlusion between his upper and lower teeth.Shortly after the original post was written, Tim successfully had the problematic canine removed.