Life as a suspension feeder is a mixed blessing. Most suspension feeders are sessile, staying in one place for practically their entire life. They feed by extracting food particles from water, using a bewildering variety of suction tubes, mucus nets, feathery appendages, and various other anatomical variations. Almost every phylum of animals and many protists include examples of suspension feeders. It's a lifestyle that could be regarded almost as idyllic, as you sway back and forth in the current, waiting on food to blunder into your mouth (for those suspension feeders that actually have mouths; not all do). But it can be treacherous, too. Those same currents that bring you your food can also rip you from your anchor point, carrying you off, where you may ironically end up as food for some other suspension feeder. Attaching to a solid, stable substrate is critical to survival for a suspension feeder, and in some environments there is a lot of competition for good spots.Above is a shell of the extinct scallop Chesapecten madisonius, a species that was abundant in warm-temperate waters of the western Atlantic during the Pliocene. This example came from a quarry near Chuckatuck, Virginia, from the 3-million-year-old Yorktown Formation. Scallops are suspension feeders, although they are capable of moving around. When they died, their large (up to the size of a dinner plate!) calcium carbonate shells would end up lying on the seafloor.At this particular location, the sediment is almost all sand, with huge numbers of broken seashells. Both the sediment and types and preservation of the shells indicate that this was an offshore shoaling area where waves were breaking in shallow water. With the constant water flow this was a great environment for suspension feeders, but the high energy and unconsolidated sandy bottom mean that hard substrates for attachment were at a premium. A large mineralized seashell sitting on the seafloor was too good to pass up, and a whole community of suspension feeders took advantage and settled on the shell.Some of these organisms are gone, but left traces behind indicating their presence. There are several pits at various places on the shell:

Life as a suspension feeder is a mixed blessing. Most suspension feeders are sessile, staying in one place for practically their entire life. They feed by extracting food particles from water, using a bewildering variety of suction tubes, mucus nets, feathery appendages, and various other anatomical variations. Almost every phylum of animals and many protists include examples of suspension feeders. It's a lifestyle that could be regarded almost as idyllic, as you sway back and forth in the current, waiting on food to blunder into your mouth (for those suspension feeders that actually have mouths; not all do). But it can be treacherous, too. Those same currents that bring you your food can also rip you from your anchor point, carrying you off, where you may ironically end up as food for some other suspension feeder. Attaching to a solid, stable substrate is critical to survival for a suspension feeder, and in some environments there is a lot of competition for good spots.Above is a shell of the extinct scallop Chesapecten madisonius, a species that was abundant in warm-temperate waters of the western Atlantic during the Pliocene. This example came from a quarry near Chuckatuck, Virginia, from the 3-million-year-old Yorktown Formation. Scallops are suspension feeders, although they are capable of moving around. When they died, their large (up to the size of a dinner plate!) calcium carbonate shells would end up lying on the seafloor.At this particular location, the sediment is almost all sand, with huge numbers of broken seashells. Both the sediment and types and preservation of the shells indicate that this was an offshore shoaling area where waves were breaking in shallow water. With the constant water flow this was a great environment for suspension feeders, but the high energy and unconsolidated sandy bottom mean that hard substrates for attachment were at a premium. A large mineralized seashell sitting on the seafloor was too good to pass up, and a whole community of suspension feeders took advantage and settled on the shell.Some of these organisms are gone, but left traces behind indicating their presence. There are several pits at various places on the shell:

A few of these were probably made by predatory snails that attack other mollusks by drilling into their shells. Others were likely formed by cloned sponges, which chemically dissolve part of the target shell to provide living space.In other areas, parts of the shell have been broadly removed, leaving shallow sculpted depressions:

A few of these were probably made by predatory snails that attack other mollusks by drilling into their shells. Others were likely formed by cloned sponges, which chemically dissolve part of the target shell to provide living space.In other areas, parts of the shell have been broadly removed, leaving shallow sculpted depressions: These were likely produced by another mollusk, possibly slipper snails such as Crepidula or boring clams from the family that includes shipworms (which are actually clams). Some were definitely clams of some sort, because one of the shells is still there (although I've not yet been able to identify the species):

These were likely produced by another mollusk, possibly slipper snails such as Crepidula or boring clams from the family that includes shipworms (which are actually clams). Some were definitely clams of some sort, because one of the shells is still there (although I've not yet been able to identify the species): In many cases the colonizing organisms' shells are still present. The most obvious are these volcano-shaped structures:

In many cases the colonizing organisms' shells are still present. The most obvious are these volcano-shaped structures: These are barnacles, sessile suspension-feeding crustaceans that are distantly related to shrimp (as a nod to the evolutionary imagination of suspension feeders, they collect food by waving their hairy legs around in the water). Sitting between two barnacles is (I think) an attachment point for an oyster:

These are barnacles, sessile suspension-feeding crustaceans that are distantly related to shrimp (as a nod to the evolutionary imagination of suspension feeders, they collect food by waving their hairy legs around in the water). Sitting between two barnacles is (I think) an attachment point for an oyster: Nearby are small carbonate tubes. I believe these are tubes from polychaete worms (there are also clams that build carbonate tubes, but I'm pretty sure these are from worms):

Nearby are small carbonate tubes. I believe these are tubes from polychaete worms (there are also clams that build carbonate tubes, but I'm pretty sure these are from worms): In terms of coverage area, the most extensive colonizers on this shell are bryozoans, or moss animals. These are colonial animals that are placed in their own phylum. Here's one of the larger colonies on this shell:

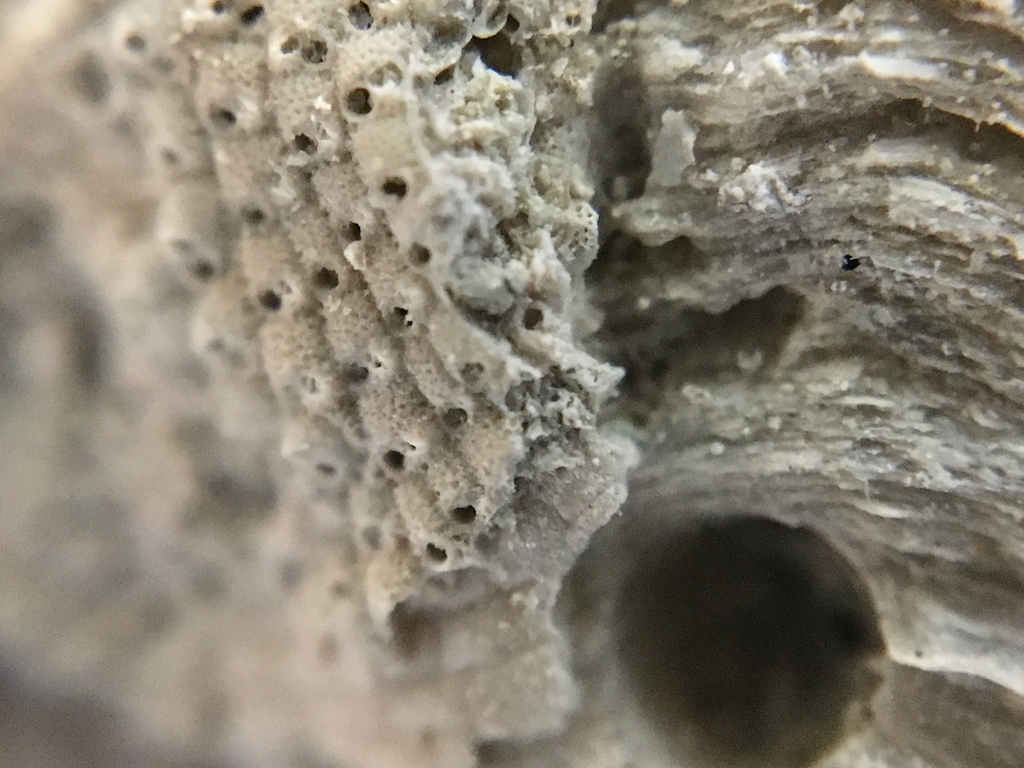

In terms of coverage area, the most extensive colonizers on this shell are bryozoans, or moss animals. These are colonial animals that are placed in their own phylum. Here's one of the larger colonies on this shell: Zooming in close, we can see the individual animals ("zooids") in the colony; each hole contained a zooid:

Zooming in close, we can see the individual animals ("zooids") in the colony; each hole contained a zooid: It seems that this shell was colonized by at least two species of bryozoans, because there's another area where the zooids look rather different:

It seems that this shell was colonized by at least two species of bryozoans, because there's another area where the zooids look rather different: Finally, there's one I'm really uncertain about. There's one patch (the yellowish area at the center of the shell in the top image) where a barnacle attached itself on top of the bryozoan colony, and then fell off (the yellow area is the base of the barnacle). But, on top of that, there are a handful of tiny spiral shells, the largest of which is just under 1 mm in diameter:

Finally, there's one I'm really uncertain about. There's one patch (the yellowish area at the center of the shell in the top image) where a barnacle attached itself on top of the bryozoan colony, and then fell off (the yellow area is the base of the barnacle). But, on top of that, there are a handful of tiny spiral shells, the largest of which is just under 1 mm in diameter: I'm not completely sure of my identification here, but I think these are benthic foraminifera. Foraminifera are amoeba-like, single-celled protists that secrete a calcium carbonate shell (in most species). There are perhaps a dozen of these visible, in addition to places where they were clearly present at one time and later removed.So, assuming all my identifications are correct, and counting everything up, this single Chesapecten shell supported:

I'm not completely sure of my identification here, but I think these are benthic foraminifera. Foraminifera are amoeba-like, single-celled protists that secrete a calcium carbonate shell (in most species). There are perhaps a dozen of these visible, in addition to places where they were clearly present at one time and later removed.So, assuming all my identifications are correct, and counting everything up, this single Chesapecten shell supported:

- A sponge

- At least a half-dozen bivalves, from at least two species

- At least 10 barnacles

- At least a dozen polychaete worms

- At least two bryozoan species each with several hundred individuals

- At least a dozen foraminifera

Not bad for a single seashell!