Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image):

Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image): These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.

These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.

Fossil Friday - Smilodon vertebra

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

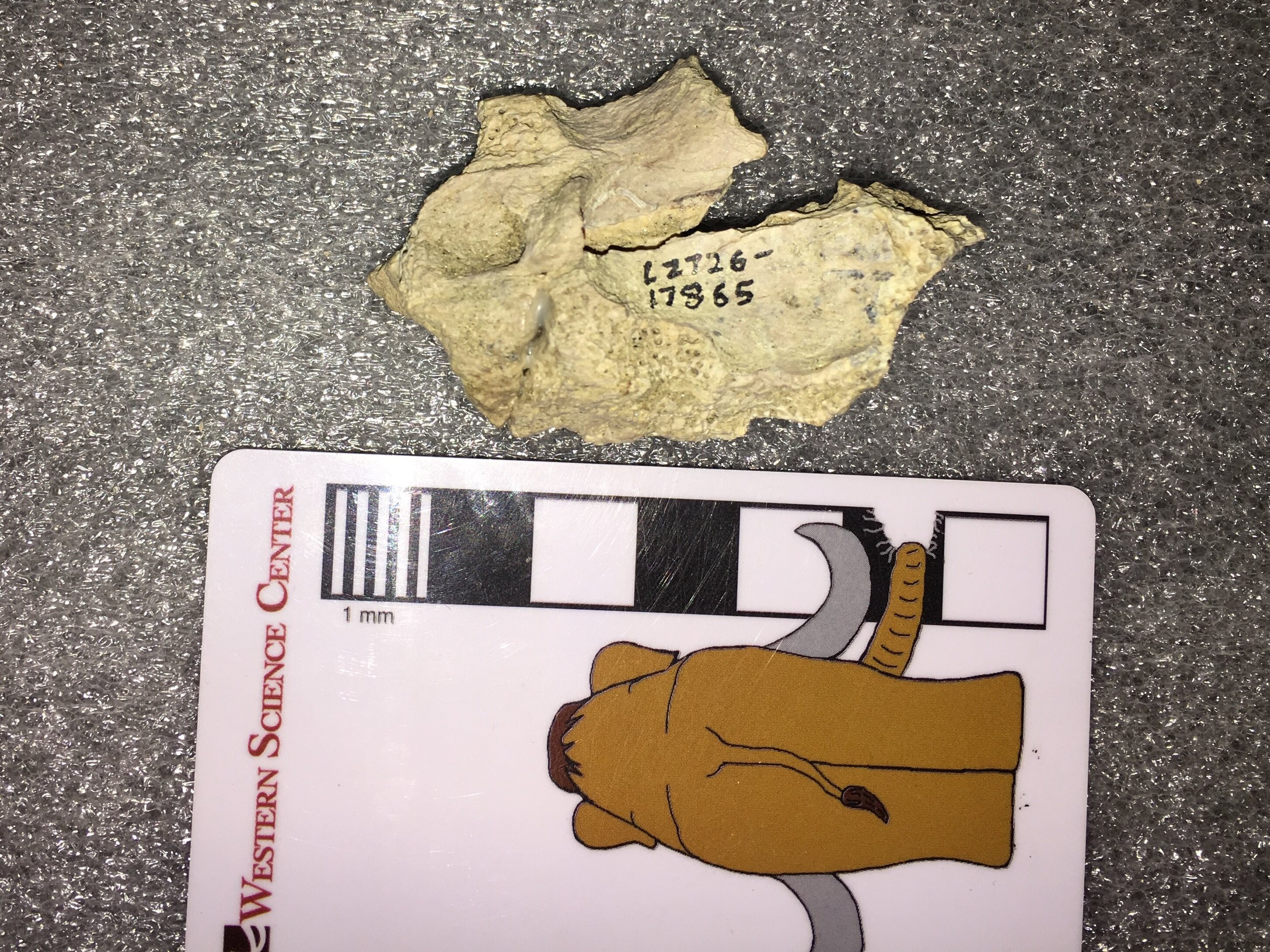

Fossil Friday - cat skull fragments

With many fossils, particularly vertebrates, small fragments can sometimes be very informative and justify close scrutiny. That was the case with a pair of associated bones from Diamond Valley Lake. One of the fragments, shown above, includes the occipital condyles that form the articulation between the skull and the first vertebra. The condyles sit on either side of the foramen magnum, the opening through which the spinal cord passes.The second fragment, below, appears to be part of the bottom of the skull just anterior to the condyles, including portions of the left squamosal and basisphenoid.

With many fossils, particularly vertebrates, small fragments can sometimes be very informative and justify close scrutiny. That was the case with a pair of associated bones from Diamond Valley Lake. One of the fragments, shown above, includes the occipital condyles that form the articulation between the skull and the first vertebra. The condyles sit on either side of the foramen magnum, the opening through which the spinal cord passes.The second fragment, below, appears to be part of the bottom of the skull just anterior to the condyles, including portions of the left squamosal and basisphenoid.  The initial DVL report identified these fragments as coming from a cat, but the type of cat was uncertain. They appear to be far too large to come from a mountain lion, and the report suggests they may be from a jaguar, Panthera onca. Today jaguars are only found in South America and as far north as Mexico (except for one individual roaming the mountains near Tucson, Arizona), but the species originated in North America and was widespread in the southern US states during the Pleistocene. However, as pointed out in the DVL report, it was very rare in the Pleistocene of Southern California and would be a surprising find at Diamond Valley Lake. We have a cast jaguar skull in our teaching collection that allows for comparison:

The initial DVL report identified these fragments as coming from a cat, but the type of cat was uncertain. They appear to be far too large to come from a mountain lion, and the report suggests they may be from a jaguar, Panthera onca. Today jaguars are only found in South America and as far north as Mexico (except for one individual roaming the mountains near Tucson, Arizona), but the species originated in North America and was widespread in the southern US states during the Pleistocene. However, as pointed out in the DVL report, it was very rare in the Pleistocene of Southern California and would be a surprising find at Diamond Valley Lake. We have a cast jaguar skull in our teaching collection that allows for comparison: The DVL specimen is much larger than the modern cast, but that's not a problem; Pleistocene jaguars were larger than modern ones. The shape is somewhat similar, but there are differences in the shape of the condyles. In an oblique ventral view (below) it's also clear that the basioccipital (the bone just in front of the condyles) is shaped quite differently:

The DVL specimen is much larger than the modern cast, but that's not a problem; Pleistocene jaguars were larger than modern ones. The shape is somewhat similar, but there are differences in the shape of the condyles. In an oblique ventral view (below) it's also clear that the basioccipital (the bone just in front of the condyles) is shaped quite differently: As it turns out, this fragment is a pretty close (if not perfect) match in size and shape for our cast of Smilodon from Rancholabrean La Brea:

As it turns out, this fragment is a pretty close (if not perfect) match in size and shape for our cast of Smilodon from Rancholabrean La Brea: Turning to the squamosal, below is the relevant area on our cast Smilodon; note that an additional bone, the tympanic bulla, is cast into this specimen and obscures part of the squamosal:

Turning to the squamosal, below is the relevant area on our cast Smilodon; note that an additional bone, the tympanic bulla, is cast into this specimen and obscures part of the squamosal: Here's the same area with the DVL squamosal superimposed:

Here's the same area with the DVL squamosal superimposed: This appears to be a very close match. There's no single feature that definitively places these bones in Smilodon, but it seems to be a closer match than Panthera onca. Moreover, while jaguars are rare in Southern California and otherwise unknown from Diamond Valley Lake, sabertooth cats are very common in Southern California deposits and are known from several DVL sites. Taken together, I think everything points to this specimen being Smilodon.* Edited to include the correct the range of the modern jaguar.

This appears to be a very close match. There's no single feature that definitively places these bones in Smilodon, but it seems to be a closer match than Panthera onca. Moreover, while jaguars are rare in Southern California and otherwise unknown from Diamond Valley Lake, sabertooth cats are very common in Southern California deposits and are known from several DVL sites. Taken together, I think everything points to this specimen being Smilodon.* Edited to include the correct the range of the modern jaguar.

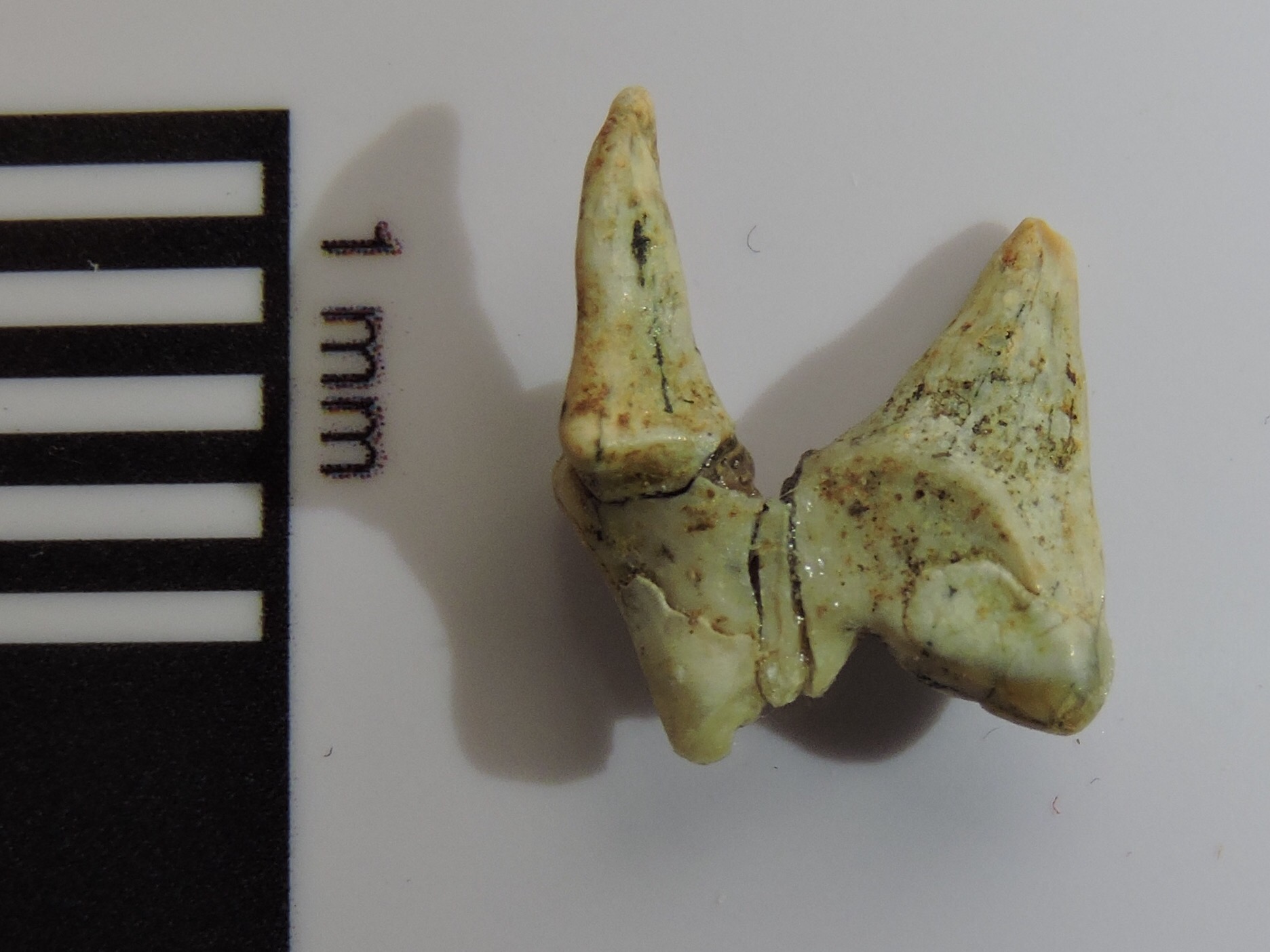

Fossil Friday - possible bobcat tooth

Confession time: I'm not an expert on most of the organisms I feature on Fossil Friday, and it sometimes takes me a fair bit of research to work out what I'm going to say. Because of that, when I'm swamped with other work (like this week), I will usually pick a Fossil Friday specimen that is straightforward so that I can write about it quickly. But sometimes the choice backfires.One of the rarest fossils from Diamond Valley Lake is the bobcat, represented by a single tooth and possibly two other bones. Confirming the identity of a bobcat tooth should be relatively straightforward, especially since we recently acquired a modern bobcat skull for comparison. Our database indicated that the single tooth is a lower first molar, broken into three fragments. In carnivorans such as cats, the lower 1st molar is modified into a large blade-shaped tooth. The upper 4th premolar is modified in a similar way, and these two teeth (called the carnassials) occlude like a pair of scissors, slicing up meat. A quick glance at the three tooth fragments confirmed that the carnassial blade structure was present. As long as I had the tooth out, I decided to glue the fragments back together, with the result shown above in lingual view and below in labial view.

Confession time: I'm not an expert on most of the organisms I feature on Fossil Friday, and it sometimes takes me a fair bit of research to work out what I'm going to say. Because of that, when I'm swamped with other work (like this week), I will usually pick a Fossil Friday specimen that is straightforward so that I can write about it quickly. But sometimes the choice backfires.One of the rarest fossils from Diamond Valley Lake is the bobcat, represented by a single tooth and possibly two other bones. Confirming the identity of a bobcat tooth should be relatively straightforward, especially since we recently acquired a modern bobcat skull for comparison. Our database indicated that the single tooth is a lower first molar, broken into three fragments. In carnivorans such as cats, the lower 1st molar is modified into a large blade-shaped tooth. The upper 4th premolar is modified in a similar way, and these two teeth (called the carnassials) occlude like a pair of scissors, slicing up meat. A quick glance at the three tooth fragments confirmed that the carnassial blade structure was present. As long as I had the tooth out, I decided to glue the fragments back together, with the result shown above in lingual view and below in labial view. The tooth still shows a lot of damage, but one thing that was immediately clear was that the tooth originally had three roots; that meant it was an upper tooth. Instead of a lower left 1st molar, it's actually an upper right 4th premolar. Here's an occlusal view of the tooth:

The tooth still shows a lot of damage, but one thing that was immediately clear was that the tooth originally had three roots; that meant it was an upper tooth. Instead of a lower left 1st molar, it's actually an upper right 4th premolar. Here's an occlusal view of the tooth: The knob projecting to the upper right (toward the front and middling of the skull, or "anterolingually") is called the protocone. A root is located directly under the protocone. The protocone and its associated root were broken off as a separate piece, which I suspect is what caused the misidentification.So, now that the tooth is an upper 4th premolar instead of a lower 1st molar, can we still call it a bobcat? Unfortunately, that's not entirely clear. Below is an occlusal view of a bobcat's upper 4th premolar:

The knob projecting to the upper right (toward the front and middling of the skull, or "anterolingually") is called the protocone. A root is located directly under the protocone. The protocone and its associated root were broken off as a separate piece, which I suspect is what caused the misidentification.So, now that the tooth is an upper 4th premolar instead of a lower 1st molar, can we still call it a bobcat? Unfortunately, that's not entirely clear. Below is an occlusal view of a bobcat's upper 4th premolar: While these teeth are similar in some ways, there are some important differences. For example, the lingual edge of the tooth is slightly convex in the bobcat, but slightly concave in the DVL specimen. The bobcat tooth is also about 10% larger.In terms of size, the DVL tooth is actually closer to a gray fox:

While these teeth are similar in some ways, there are some important differences. For example, the lingual edge of the tooth is slightly convex in the bobcat, but slightly concave in the DVL specimen. The bobcat tooth is also about 10% larger.In terms of size, the DVL tooth is actually closer to a gray fox: While the size is good, the shape of the DVL tooth still differs quite a bit from the gray fox, particularly the shape of the anterior edge. On balance, in spite of the size, I think this tooth is still more similar to a bobcat than anything else I've seen. Until we can study it further, I think we can tentatively call it a bobcat.

While the size is good, the shape of the DVL tooth still differs quite a bit from the gray fox, particularly the shape of the anterior edge. On balance, in spite of the size, I think this tooth is still more similar to a bobcat than anything else I've seen. Until we can study it further, I think we can tentatively call it a bobcat.

Fossil Friday - coyote jaw

The deer bones I talked about a few weeks ago are part of a small assemblage from a housing development in Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. Among the other remains in the collection was a partial dentary (lower jaw) from a carnivore.The fragment is a right dentary, shown above in lateral view with anterior to the right. Below is medial view, with anterior to the left:

The deer bones I talked about a few weeks ago are part of a small assemblage from a housing development in Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. Among the other remains in the collection was a partial dentary (lower jaw) from a carnivore.The fragment is a right dentary, shown above in lateral view with anterior to the right. Below is medial view, with anterior to the left: And here's the dorsal view, with anterior to the left.

And here's the dorsal view, with anterior to the left. The teeth are mostly missing, but the back half of the third premolar and the anterior root of the fourth premolar are preserved. Below is dorsal view with the sockets labeled:

The teeth are mostly missing, but the back half of the third premolar and the anterior root of the fourth premolar are preserved. Below is dorsal view with the sockets labeled: This fragment is a good match in both size and morphology for the front half of a coyote, Canis latrans, which have been common in California since the Pleistocene:

This fragment is a good match in both size and morphology for the front half of a coyote, Canis latrans, which have been common in California since the Pleistocene:

Fossil Friday - Carnivore traces

In any large collection of vertebrate fossils, one of the more common specimen labels will be "unidentified bone fragment". But even an unidentified fragment can provide useful information. The bone shown above, found near the East Dam of DVL, has the following, rather uninspiring label: "Mammalia (larger size), unidentified bone fragment". This might be part of a transverse process or neural spine from a vertebra, and if so is could be from anything from a horse to a juvenile proboscidean. But there are also other possibilities; about the only things we can rule out are animals like rodents and rabbits that don't have any bones at all that are this large.So why is this bone interesting? Note the grooves visible in several places along the margin. Here are some views from different angles:

In any large collection of vertebrate fossils, one of the more common specimen labels will be "unidentified bone fragment". But even an unidentified fragment can provide useful information. The bone shown above, found near the East Dam of DVL, has the following, rather uninspiring label: "Mammalia (larger size), unidentified bone fragment". This might be part of a transverse process or neural spine from a vertebra, and if so is could be from anything from a horse to a juvenile proboscidean. But there are also other possibilities; about the only things we can rule out are animals like rodents and rabbits that don't have any bones at all that are this large.So why is this bone interesting? Note the grooves visible in several places along the margin. Here are some views from different angles:

These nearly-parallel grooves are consistent with gnaw marks from a carnivoran, so this fragment is covered with trace fossils. We can't say with certainty what type of carnivoran made the marks, but they are not particularly large, so it's unlikely we're looking at a huge animal like Arctodus. A medium-sized carnivoran such as a black bear, dire wolf, or coyote is a more likely possibility, or perhaps even a badger; all of these are known from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.As I've mentioned in previous posts, carnivoran bones are quite rare in the DVL deposits. But we do see evidence of their activity. We haven't yet catalogued all the bite marks that are present on DVL bones, but I suspect we actually have more carnivoran trace fossils than bones in our collection.

These nearly-parallel grooves are consistent with gnaw marks from a carnivoran, so this fragment is covered with trace fossils. We can't say with certainty what type of carnivoran made the marks, but they are not particularly large, so it's unlikely we're looking at a huge animal like Arctodus. A medium-sized carnivoran such as a black bear, dire wolf, or coyote is a more likely possibility, or perhaps even a badger; all of these are known from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.As I've mentioned in previous posts, carnivoran bones are quite rare in the DVL deposits. But we do see evidence of their activity. We haven't yet catalogued all the bite marks that are present on DVL bones, but I suspect we actually have more carnivoran trace fossils than bones in our collection.

Fossil Friday - dire wolf tooth

Today is National Dog Day, and while the day is primarily honoring domestic dogs (Canis familiaris, or Canis lupus familiars), it seems fitting to also recognize their wild ancestors and cousins.The Diamond Valley Lake deposits only produced a handful of carnivores bones, but several canids are included among their numbers. There are a few individual bones and teeth from dire wolves (Canis dirus), the same species that is so spectacularly common at Rancho La Brea, 80 miles to the west.The partial tooth shown above is currently on exhibit at the Western Science Center, so rather than open the exhibit case (a 3-hour exercise) I instead photographed it through the glass. This rather large tooth is a carnassial, shearing teeth developed to varying degrees among all the carnivorans. The upper carnassials are modified 4th premolars, while the lower ones are the first molars. These teeth occlude like a pair of scissors, and are effective at chopping up flesh from prey animals.While it's difficult to do a detailed examination through glass, I'm pretty sure this is the upper right 4th premolar, seen in lingual view, with the anterior edge broken off and the point worn away. Compare it to a modern coyote upper P4 in the same orientation, below:

Today is National Dog Day, and while the day is primarily honoring domestic dogs (Canis familiaris, or Canis lupus familiars), it seems fitting to also recognize their wild ancestors and cousins.The Diamond Valley Lake deposits only produced a handful of carnivores bones, but several canids are included among their numbers. There are a few individual bones and teeth from dire wolves (Canis dirus), the same species that is so spectacularly common at Rancho La Brea, 80 miles to the west.The partial tooth shown above is currently on exhibit at the Western Science Center, so rather than open the exhibit case (a 3-hour exercise) I instead photographed it through the glass. This rather large tooth is a carnassial, shearing teeth developed to varying degrees among all the carnivorans. The upper carnassials are modified 4th premolars, while the lower ones are the first molars. These teeth occlude like a pair of scissors, and are effective at chopping up flesh from prey animals.While it's difficult to do a detailed examination through glass, I'm pretty sure this is the upper right 4th premolar, seen in lingual view, with the anterior edge broken off and the point worn away. Compare it to a modern coyote upper P4 in the same orientation, below: So if you're celebrating National Dog Day, maybe take some time to visit your local natural history museum and remember our canine friends' extinct relatives!

So if you're celebrating National Dog Day, maybe take some time to visit your local natural history museum and remember our canine friends' extinct relatives!

For those in Southern California, the Western Science Center will be attending NerdCon at the California Center for the Arts in Escondido this weekend. There will be opportunities to take selfies with Max, and we'll have numerous replicas on display (including a dire wolf skull). You'll also be able to purchase detailed replicas of some of our fossils, so if you're attending NerdCon make sure to stop by our booth!

Fossil Friday - Homotherium jaw

A basic tenet of ecology is that as you move higher up a food chain, the biomass (and usually number of individual animals) will get smaller. Each trophic level in a food chain gets its energy from the level below, and since there is never a perfect 100% energy transfer there is always less energy available at higher levels. This has a profound impact on the fossil record; in general, "top-of-the-food-chain" carnivores are exceptionally rare as fossils, because they were also rare as living animals. (If you spend time outdoors, think about how many squirrels, rabbits, and deer you've ever seen, compared to the number of coyotes and bobcats.) While there are occasional exceptions such as the predator trap at Rancho La Brea that bias the fossil record in favor of carnivores, at most localities large carnivores are rare.The fossils Southern California Edison El Casco Substation site are dominated by rodents, horses, and other herbivores, but a handful of large carnivores were also discovered. One of the most fascinating is the "other" Ice Age sabertooth cat, Homotherium.A number of bones from one individual of Homotherium were collected at El Casco, including the right dentary (lower jaw) shown here. At the top is the lateral view, and below is the medial view:

A basic tenet of ecology is that as you move higher up a food chain, the biomass (and usually number of individual animals) will get smaller. Each trophic level in a food chain gets its energy from the level below, and since there is never a perfect 100% energy transfer there is always less energy available at higher levels. This has a profound impact on the fossil record; in general, "top-of-the-food-chain" carnivores are exceptionally rare as fossils, because they were also rare as living animals. (If you spend time outdoors, think about how many squirrels, rabbits, and deer you've ever seen, compared to the number of coyotes and bobcats.) While there are occasional exceptions such as the predator trap at Rancho La Brea that bias the fossil record in favor of carnivores, at most localities large carnivores are rare.The fossils Southern California Edison El Casco Substation site are dominated by rodents, horses, and other herbivores, but a handful of large carnivores were also discovered. One of the most fascinating is the "other" Ice Age sabertooth cat, Homotherium.A number of bones from one individual of Homotherium were collected at El Casco, including the right dentary (lower jaw) shown here. At the top is the lateral view, and below is the medial view: The dentary is largely complete, although there is some damage at each end, and several teeth are broken. There is a flange on the bottom edge at the front of the jaw; this is a common feature in sabertooth cats (and some other saber-toothed animals) to help protect the long upper canine teeth.Below is a dorsal view, showing the occlusal side of the teeth:

The dentary is largely complete, although there is some damage at each end, and several teeth are broken. There is a flange on the bottom edge at the front of the jaw; this is a common feature in sabertooth cats (and some other saber-toothed animals) to help protect the long upper canine teeth.Below is a dorsal view, showing the occlusal side of the teeth: A labeled version of the same image:

A labeled version of the same image: Cats, including Homotherium, have a highly specialized dentition. Each half of the lower jaw includes 3 incisors and an enlarged canine. Most of the premolars and molars have been lost in advanced cats, with only the 3rd and 4th premolars and the 1st molar remaining. These are modified into sharp blades that, when occluding with the upper teeth, act like a pair of scissors for slicing meat. Cats lack a grinding molar in the back of the mouth like the kind seen in dogs, and as a result are much less likely to gnaw on or attempt to crack open the bones of their prey.One of the unusual features of Homotherium is its enlarged incisors. It's not obvious in this specimen because the canine tooth is broken, but the lower incisors were almost as large as the canine, and protrude more from the front of the mouth than in most other cats. There's a beautiful illustration of Homotherium by Mauricio Anton that shows details of the unusual dentition.Homotherium was a large, tiger-sized cat with rather short back legs compared to the front legs, as can be seen in the reconstructed skeleton at the Texas Memorial Museum show below. Several different species of Homotherium are known from both the New World and the Old World, and they probably filled a variety of different ecological niches. There is at least one site in Texas that suggests that a Homotherium population there may have had a preference for juvenile mammoths as prey items, but mammoths are exceptionally rare in the sediments that produced the El Casco Homotherium.

Cats, including Homotherium, have a highly specialized dentition. Each half of the lower jaw includes 3 incisors and an enlarged canine. Most of the premolars and molars have been lost in advanced cats, with only the 3rd and 4th premolars and the 1st molar remaining. These are modified into sharp blades that, when occluding with the upper teeth, act like a pair of scissors for slicing meat. Cats lack a grinding molar in the back of the mouth like the kind seen in dogs, and as a result are much less likely to gnaw on or attempt to crack open the bones of their prey.One of the unusual features of Homotherium is its enlarged incisors. It's not obvious in this specimen because the canine tooth is broken, but the lower incisors were almost as large as the canine, and protrude more from the front of the mouth than in most other cats. There's a beautiful illustration of Homotherium by Mauricio Anton that shows details of the unusual dentition.Homotherium was a large, tiger-sized cat with rather short back legs compared to the front legs, as can be seen in the reconstructed skeleton at the Texas Memorial Museum show below. Several different species of Homotherium are known from both the New World and the Old World, and they probably filled a variety of different ecological niches. There is at least one site in Texas that suggests that a Homotherium population there may have had a preference for juvenile mammoths as prey items, but mammoths are exceptionally rare in the sediments that produced the El Casco Homotherium.

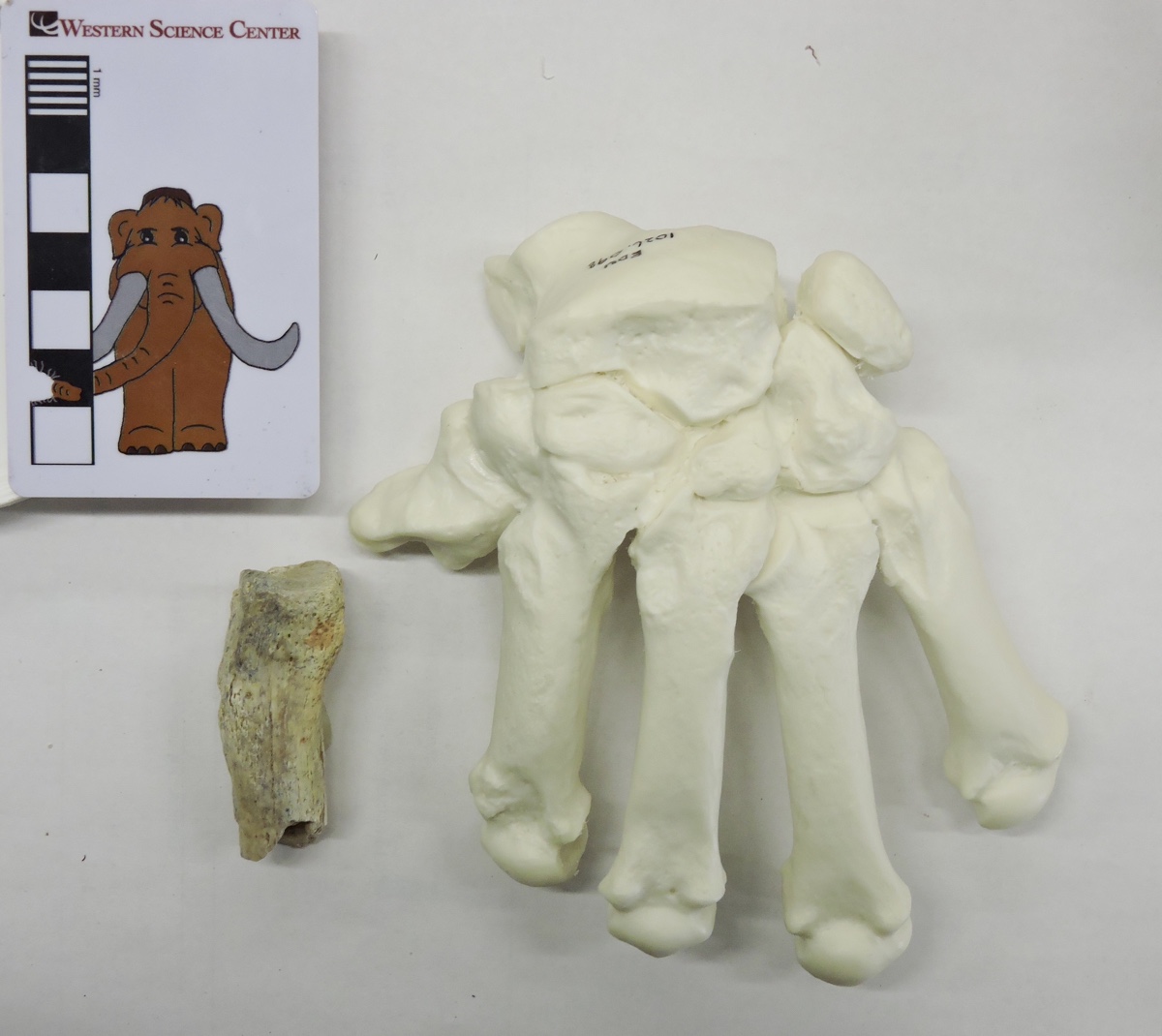

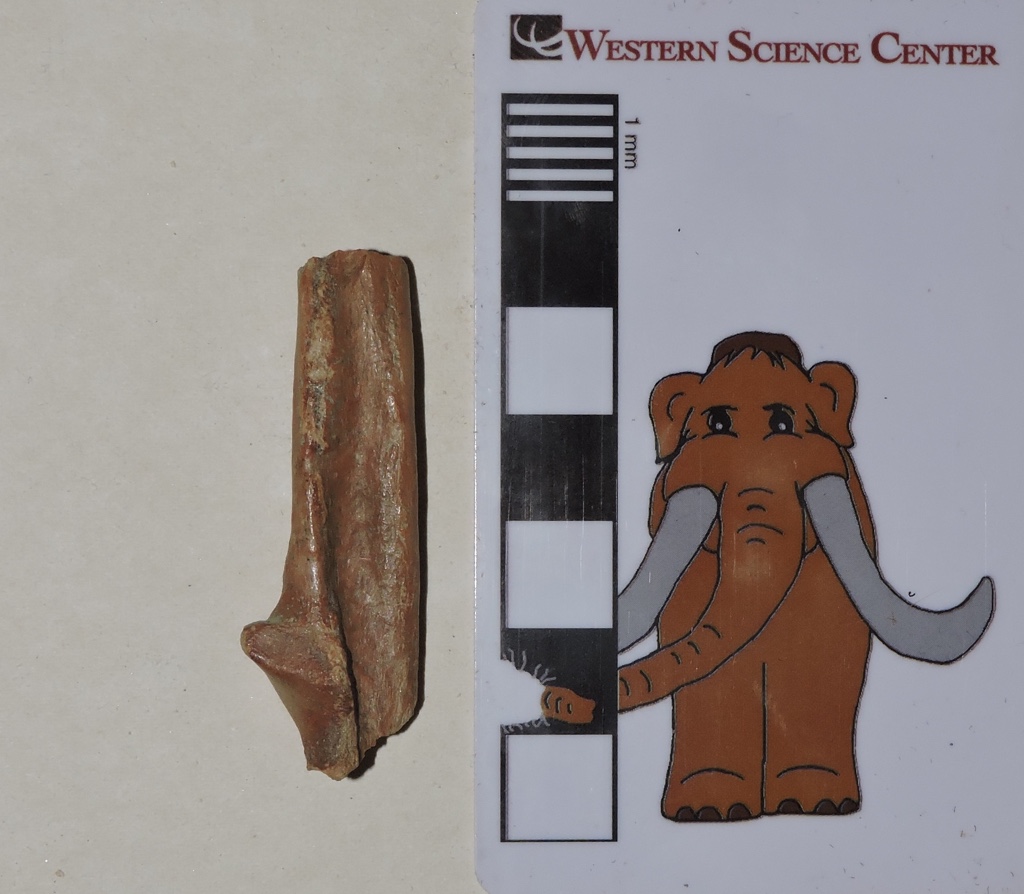

Fossil Friday - Smilodon metacarpal

Part of the nature of paleontology is attempting to pull as much information as possible out of often very limited data. As I mentioned last week, many fossil specimens may not be especially visually compelling, but nevertheless can provide useful information.A few weeks ago I discussed a bighorn sheep bone from a small collection of fossils recovered from Bureau of Land Management property near Desert Center in Riverside County. A number of other species were found at this site, with one of the most surprising being the sabertooth cat Smilodon.The only identifiable fragment from Smilodon that was found was the partial left second metacarpal (the hand bone that supports the index finger) shown above. It happens that at WSC we have a cast skeleton of Smilodon that we use for programming that allows us to place it in context:

Part of the nature of paleontology is attempting to pull as much information as possible out of often very limited data. As I mentioned last week, many fossil specimens may not be especially visually compelling, but nevertheless can provide useful information.A few weeks ago I discussed a bighorn sheep bone from a small collection of fossils recovered from Bureau of Land Management property near Desert Center in Riverside County. A number of other species were found at this site, with one of the most surprising being the sabertooth cat Smilodon.The only identifiable fragment from Smilodon that was found was the partial left second metacarpal (the hand bone that supports the index finger) shown above. It happens that at WSC we have a cast skeleton of Smilodon that we use for programming that allows us to place it in context: Here's a marked-up version, with the approximate preserved portion of the metacarpal indicated:

Here's a marked-up version, with the approximate preserved portion of the metacarpal indicated: So all we have is the proximal half of the bone, and even that is damaged. Nevertheless, the size and shape make this a pretty solid identification. The interesting thing is that this is the only reported Smilodon bone from the entire region around Desert Center, and in fact is the only record of any large Pleistocene cat from this area (Raum et al. 2014). So this tiny fragment turns out to be a relatively significant specimen for what it can potentially tell us about the range of Smilodon and the Pleistocene ecosystem in the Desert Center region.Reference: Raum, J., Aron, G. L., and Reynolds, R. E., 2014. Vertebrate fossils from Desert Center, Chuckwalla Valley, California. In R. E. Reynolds (Ed.), Not a Drop Left to Drink, California State University Desert Studies Center 2014 Desert Symposium: 68-70.

So all we have is the proximal half of the bone, and even that is damaged. Nevertheless, the size and shape make this a pretty solid identification. The interesting thing is that this is the only reported Smilodon bone from the entire region around Desert Center, and in fact is the only record of any large Pleistocene cat from this area (Raum et al. 2014). So this tiny fragment turns out to be a relatively significant specimen for what it can potentially tell us about the range of Smilodon and the Pleistocene ecosystem in the Desert Center region.Reference: Raum, J., Aron, G. L., and Reynolds, R. E., 2014. Vertebrate fossils from Desert Center, Chuckwalla Valley, California. In R. E. Reynolds (Ed.), Not a Drop Left to Drink, California State University Desert Studies Center 2014 Desert Symposium: 68-70.

Fossil Friday - badger ulna

It happens that last Tuesday, October 6, was National Badger Day in Britain. While the European badger Meles meles does not occur in North America, why should that stop us from honoring badgers? The American badger Taxidea taxus (above at The Living Desert Zoo) is only distantly related to the European badger, but it still goes by the common name of "badger", and that's good enough for me!Taxidea is widespread in North America today, so it's no surprise that is occasionally turns up in Pleistocene deposits. A handful of badger bones were found in the Diamond Valley Lake excavations, including this right ulna:

It happens that last Tuesday, October 6, was National Badger Day in Britain. While the European badger Meles meles does not occur in North America, why should that stop us from honoring badgers? The American badger Taxidea taxus (above at The Living Desert Zoo) is only distantly related to the European badger, but it still goes by the common name of "badger", and that's good enough for me!Taxidea is widespread in North America today, so it's no surprise that is occasionally turns up in Pleistocene deposits. A handful of badger bones were found in the Diamond Valley Lake excavations, including this right ulna:

This fragment represents roughly the middle third of the ulna, one of the bones in the forearm. If that doesn't seem like much, keep in mind that badger bones make up roughly 0.0015% of the bones collected from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits, so even with such a small piece we're doing pretty well!

This fragment represents roughly the middle third of the ulna, one of the bones in the forearm. If that doesn't seem like much, keep in mind that badger bones make up roughly 0.0015% of the bones collected from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits, so even with such a small piece we're doing pretty well!

Fossil Friday - coyote humerus

As I've mentioned in several other posts, fossil carnivores are rare in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna, but they're not completely absent. The remains tend to be isolated bone fragments, but they do reveal the presence of the particular taxon. The small fragment shown here is part of a right humerus from a canid (the dog family). Both ends of the bone are missing, but this fragment comes from closer to the distal end (towards the elbow). Three weeks ago I posted about another canid right humerus, probably from a dire wolf. It's useful to see these specimens side-by-side:

As I've mentioned in several other posts, fossil carnivores are rare in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna, but they're not completely absent. The remains tend to be isolated bone fragments, but they do reveal the presence of the particular taxon. The small fragment shown here is part of a right humerus from a canid (the dog family). Both ends of the bone are missing, but this fragment comes from closer to the distal end (towards the elbow). Three weeks ago I posted about another canid right humerus, probably from a dire wolf. It's useful to see these specimens side-by-side:  Even though this week's specimen is fragmentary, it's clearly smaller than the dire wolf. Its size is consistent with Canis latrans, the coyote. Coyotes are among the most common mammals at Rancho la Brea, and are still common in Southern California, so their presence in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna is not surprising. But it's still nice to confirm their presence, especially as modern coyotes seem to fill interesting roles in modern ecosystems. There are strong indications that modern coyotes are major predators of pronghorn, but only in the absence of wolves. Apparently wolves alter the behavior of coyotes (either by attacking them or driving them away), resulting in less overall pronghorn predation. In turn, it seems that coyotes suppress populations of domestic and feral cats, reducing predation on birds. These studies hint at the complexity of the interactions within ecosystems. With the amazing range of animals in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna there must have been some fascinating biotic interactions.

Even though this week's specimen is fragmentary, it's clearly smaller than the dire wolf. Its size is consistent with Canis latrans, the coyote. Coyotes are among the most common mammals at Rancho la Brea, and are still common in Southern California, so their presence in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna is not surprising. But it's still nice to confirm their presence, especially as modern coyotes seem to fill interesting roles in modern ecosystems. There are strong indications that modern coyotes are major predators of pronghorn, but only in the absence of wolves. Apparently wolves alter the behavior of coyotes (either by attacking them or driving them away), resulting in less overall pronghorn predation. In turn, it seems that coyotes suppress populations of domestic and feral cats, reducing predation on birds. These studies hint at the complexity of the interactions within ecosystems. With the amazing range of animals in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna there must have been some fascinating biotic interactions.

Fossil Friday - canid humerus

While over 200,000 fossils were found at Diamond Valley Lake, only a tiny percentage of the specimens represent carnivores. This is actually to be expected; in any stable ecosystem prey animals always greatly outnumber their predators and so normally prey animals should be much more common as fossils. There are exceptions, such as "predator traps" like we see at Rancho la Brea, but in general the rare predator/common prey breakdown at Diamond Valley Lake is what we expect to find.That said, there is actually a fairly diverse range of predators from Diamond Valley Lake, even if most of them are known only from isolated bones like as the one shown above.This is the right humerus (upper arm bone) from a canid, the dog family. It's shown above in anterior view, with the proximal end (towards the shoulder) on the left. The proximal half of the bone is actually missing, so we only have the distal half, including the elbow joint at the right end (the condyle). The round hole through the middle of the bone near the condyle is called the supratrochlear foramen. This is a common feature in dogs, but is rare or absent in most other groups, making it a useful identification feature.Below is the medial side of the same bone, showing the sinusoidal shape that is typical of the humerus in carnivores:

While over 200,000 fossils were found at Diamond Valley Lake, only a tiny percentage of the specimens represent carnivores. This is actually to be expected; in any stable ecosystem prey animals always greatly outnumber their predators and so normally prey animals should be much more common as fossils. There are exceptions, such as "predator traps" like we see at Rancho la Brea, but in general the rare predator/common prey breakdown at Diamond Valley Lake is what we expect to find.That said, there is actually a fairly diverse range of predators from Diamond Valley Lake, even if most of them are known only from isolated bones like as the one shown above.This is the right humerus (upper arm bone) from a canid, the dog family. It's shown above in anterior view, with the proximal end (towards the shoulder) on the left. The proximal half of the bone is actually missing, so we only have the distal half, including the elbow joint at the right end (the condyle). The round hole through the middle of the bone near the condyle is called the supratrochlear foramen. This is a common feature in dogs, but is rare or absent in most other groups, making it a useful identification feature.Below is the medial side of the same bone, showing the sinusoidal shape that is typical of the humerus in carnivores: Here's the posterior view:

Here's the posterior view: In this view the supratrochlear foramen is sitting in the bottom of a deep semi-circular depression, called the olecranon fossa. When the front leg is held straight, the olecranon process of the ulna (the "point" of the elbow) fits into this depression. This stabilizes the elbow and prevents the upper and lower arms from rotating in opposite directions along their long axes. To see how this works, hold your arm out straight, then rotate your arm like you're turning a screwdriver. Watch your elbow as you do this; you'll see that there's no rotation of the elbow at all, and that all the rotation is occurring either in the forearm and wrist, or at the shoulder.So, moving on from the anatomy, what kind of dog is this? This is actually a pretty large humerus by dog standards, and probably it's too large to be from a fox or a coyote (even the big Pleistocene coyotes). The distal end is damaged on its lateral side, but it looks like the bone was somewhere around 50-55 mm wide at the widest part of the distal end. At that size, this humerus is about right for either a small dire wolf (Canis dirus) or a large grey wolf (Canis lupus). There is other Diamond Valley Lake material that is pretty clearly from Canis dirus, but none that's definitively from Canis lupus (in fact, grey wolf fossils are extremely rare anywhere in California, if they're present at all), so a dire wolf is the more likely identification.

In this view the supratrochlear foramen is sitting in the bottom of a deep semi-circular depression, called the olecranon fossa. When the front leg is held straight, the olecranon process of the ulna (the "point" of the elbow) fits into this depression. This stabilizes the elbow and prevents the upper and lower arms from rotating in opposite directions along their long axes. To see how this works, hold your arm out straight, then rotate your arm like you're turning a screwdriver. Watch your elbow as you do this; you'll see that there's no rotation of the elbow at all, and that all the rotation is occurring either in the forearm and wrist, or at the shoulder.So, moving on from the anatomy, what kind of dog is this? This is actually a pretty large humerus by dog standards, and probably it's too large to be from a fox or a coyote (even the big Pleistocene coyotes). The distal end is damaged on its lateral side, but it looks like the bone was somewhere around 50-55 mm wide at the widest part of the distal end. At that size, this humerus is about right for either a small dire wolf (Canis dirus) or a large grey wolf (Canis lupus). There is other Diamond Valley Lake material that is pretty clearly from Canis dirus, but none that's definitively from Canis lupus (in fact, grey wolf fossils are extremely rare anywhere in California, if they're present at all), so a dire wolf is the more likely identification.