Today was my first official day as director of the Western Science Center. As with most new jobs, the first day was somewhat hectic, and mostly filled with paperwork.In addition to the usual tax and payroll-related paperwork, starting a new job in an academic institution like a museum also means setting up computer access and email accounts. In my case, it also means reviewing lots of museum policy documents, such as collections and ethics policies, board procedures, and budget sheets.I did get out of my office for awhile, though, for a last look at the Beatles exhibit (the exhibit closed yesterday, but we've only just started to remove it). I also took time to get to know some of the staff, and to look at some of the lab facilities. And, of course, I couldn't let my first day in the Valley of the Mastodons pass without looking at some mastodon remains:

Today was my first official day as director of the Western Science Center. As with most new jobs, the first day was somewhat hectic, and mostly filled with paperwork.In addition to the usual tax and payroll-related paperwork, starting a new job in an academic institution like a museum also means setting up computer access and email accounts. In my case, it also means reviewing lots of museum policy documents, such as collections and ethics policies, board procedures, and budget sheets.I did get out of my office for awhile, though, for a last look at the Beatles exhibit (the exhibit closed yesterday, but we've only just started to remove it). I also took time to get to know some of the staff, and to look at some of the lab facilities. And, of course, I couldn't let my first day in the Valley of the Mastodons pass without looking at some mastodon remains:

An unexpected geological obstacle

On the fourth and final day of my drive from Virginia to California, I encountered an unexpected geological obstacle: a rockfall near Flagstaff, Arizona. At least, it was unexpected to me; the locals all knew it was happening.The high, narrow roadcuts along Interstate 40 near Flagstaff have been a rockfall waiting to happen. Therefore, the Arizona Department of Transportation decided to stop waiting, and used explosives to cause a series of controlled rockfalls. One lane of traffic was closed while the rock was removed from the road. The controlled rockfall ensured that no vehicles were present underneath a natural, unplanned fall.

On the fourth and final day of my drive from Virginia to California, I encountered an unexpected geological obstacle: a rockfall near Flagstaff, Arizona. At least, it was unexpected to me; the locals all knew it was happening.The high, narrow roadcuts along Interstate 40 near Flagstaff have been a rockfall waiting to happen. Therefore, the Arizona Department of Transportation decided to stop waiting, and used explosives to cause a series of controlled rockfalls. One lane of traffic was closed while the rock was removed from the road. The controlled rockfall ensured that no vehicles were present underneath a natural, unplanned fall. After I left Arizona and drove along US95, the sparse vegetation and exposed geology reminded me that I'm not in Virginia anymore. Even though I've spent a fair amount of time in the west, I think this was the first time my car was flanked on both sides by lines of dust devils (two are visible on the right side of this photo):

After I left Arizona and drove along US95, the sparse vegetation and exposed geology reminded me that I'm not in Virginia anymore. Even though I've spent a fair amount of time in the west, I think this was the first time my car was flanked on both sides by lines of dust devils (two are visible on the right side of this photo): I'm going to spend the next week trying to take care of all the logistic hurdles involved in moving to a new city, before starting my new job the following week.

I'm going to spend the next week trying to take care of all the logistic hurdles involved in moving to a new city, before starting my new job the following week.

Water flows downhill

"Water flows downhill." It's a phrase I've always required my physical geology students to memorize, and I always ask at least one test question to ensure that they've learned it. But I do have a reason for emphasizing such a seemingly obvious point.When I was growing up in southwestern Virginia and would express my interest in geology to adults, I would often hear "You know, the New River in Virginia is one of only two rivers in the world (the other being the Nile) that flows north." When I would ask why this was the case, no one could seem to explain it. It eventually occurred to me that water could only flow downhill, and when I got my first world atlas as a birthday present I quickly discovered that there were lots of rivers that flow north, including the Niagara River, which is vigorously and emphatically flowing both north and downhill in the photo above. Yet, judging from the comments I've heard from my Virginia geology students, this myth is still alive and well. (I find it interesting that in my travels, whenever I encounter a town on a river that happens to flow north, I'm usually told by a resident that it's one of only two in the world that does so.)Because water flows downhill, it will tend to flow off of each side of linear chains of mountains. The imaginary line that runs along the crests of the mountains and divides the water flow into two directions is called, imaginatively, a divide. North America has several of them, and each one directs water off to a different ocean or drainage basin:

"Water flows downhill." It's a phrase I've always required my physical geology students to memorize, and I always ask at least one test question to ensure that they've learned it. But I do have a reason for emphasizing such a seemingly obvious point.When I was growing up in southwestern Virginia and would express my interest in geology to adults, I would often hear "You know, the New River in Virginia is one of only two rivers in the world (the other being the Nile) that flows north." When I would ask why this was the case, no one could seem to explain it. It eventually occurred to me that water could only flow downhill, and when I got my first world atlas as a birthday present I quickly discovered that there were lots of rivers that flow north, including the Niagara River, which is vigorously and emphatically flowing both north and downhill in the photo above. Yet, judging from the comments I've heard from my Virginia geology students, this myth is still alive and well. (I find it interesting that in my travels, whenever I encounter a town on a river that happens to flow north, I'm usually told by a resident that it's one of only two in the world that does so.)Because water flows downhill, it will tend to flow off of each side of linear chains of mountains. The imaginary line that runs along the crests of the mountains and divides the water flow into two directions is called, imaginatively, a divide. North America has several of them, and each one directs water off to a different ocean or drainage basin:

Image credit:"NorthAmerica-WaterDivides" by Pfly - Own work. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NorthAmerica-WaterDivides.png#mediaviewer/File:NorthAmerica-WaterDivides.png

I've crossed two divides on this trip. The first was two days ago, when I crossed the Eastern Continental Divide, which follows the Blue Ridge Escarpment for much of its length. The other I crossed today in New Mexico, the Great Continental Divide (although the "Great" is usually dropped): Pretty much all the water between these two divides eventually flows into the Gulf of Mexico. The vast majority ends up in the Mississippi River Basin, a vast area which all flows into the Mississippi River:

Pretty much all the water between these two divides eventually flows into the Gulf of Mexico. The vast majority ends up in the Mississippi River Basin, a vast area which all flows into the Mississippi River:

"Mississippi River Watershed Map" by National Park Service - http://www.nps.gov/miss/riverfacts.htm. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mississippi_River_Watershed_Map.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Mississippi_River_Watershed_Map.jpg

The Mississippi River Basin is the 5th largest river basin in the world by area; at over 3 million square kilometers it's almost half the size of Australia. The majority of this basin is relatively flat and low in elevation, and it has been that way for a long time. In fact, this basin is low enough that it's fairly unusual for it to be exposed as dry land; during much of the past 500 million years it has been below sea level, as a relatively shallow epeiric sea. For example, look at the following rocks, which were all deposited in marine settings: Cambrian Period sandstones, from Iowa

Cambrian Period sandstones, from Iowa Ordovician Period limestones, from Indiana

Ordovician Period limestones, from Indiana Silurian Period limestones, from Ohio

Silurian Period limestones, from Ohio Devonian Period shales, from Kentucky

Devonian Period shales, from Kentucky Mississippian Period limestones, from South Dakota

Mississippian Period limestones, from South Dakota Pennsylvanian Period limestones and shales, from Nebraska

Pennsylvanian Period limestones and shales, from Nebraska Permian Period limestones and shales, from South Dakota

Permian Period limestones and shales, from South Dakota Jurassic Period shales, from Wyoming

Jurassic Period shales, from Wyoming Cretaceous Period shales, from South Dakota

Cretaceous Period shales, from South Dakota Paleogene Period whale, from MississippiIf you're counting, that's an oceanic deposit in every geologic time period from the last 500 million years, except for two: the Triassic and the Neogene (the one we're in now)! The Mississippi River Basin has been mostly dry land (except for the rivers) for the last 35 million years or so, but historically that has often not been the case. Basically I spent the last two days driving across a dry seafloor, with the fossilized remains of the creatures that used to live there buried just below the surface.

Paleogene Period whale, from MississippiIf you're counting, that's an oceanic deposit in every geologic time period from the last 500 million years, except for two: the Triassic and the Neogene (the one we're in now)! The Mississippi River Basin has been mostly dry land (except for the rivers) for the last 35 million years or so, but historically that has often not been the case. Basically I spent the last two days driving across a dry seafloor, with the fossilized remains of the creatures that used to live there buried just below the surface.

Second obstacle - the Mississippi River

I stopped in western Tennessee last night, and shortly after starting up again this morning I encountered the second major geological obstacle on my trip from Virginia to California: the Mississippi River.Fortunately for me, since I'm traveling in 2014, the river did not actually present much of an obstacle. The Hernando de Soto Bridge carries Interstate 40 over the river between Tennessee and Arkansas, so I barely had to slow down:

I stopped in western Tennessee last night, and shortly after starting up again this morning I encountered the second major geological obstacle on my trip from Virginia to California: the Mississippi River.Fortunately for me, since I'm traveling in 2014, the river did not actually present much of an obstacle. The Hernando de Soto Bridge carries Interstate 40 over the river between Tennessee and Arkansas, so I barely had to slow down: Things were not always so easy. Major rivers have traditionally formed major barriers to human dispersal, influencing the direction and rate of the spread of civilizations. The first bridge over the Mississippi was only completed in 1856, between Iowa and Illinois; prior to that time the only way to move goods across the river was by ferry. The oldest surviving bridge over the Mississippi is the Eads Bridge in St. Louis, which was completed in 1874 (seen here with a newer bridge in the background):

Things were not always so easy. Major rivers have traditionally formed major barriers to human dispersal, influencing the direction and rate of the spread of civilizations. The first bridge over the Mississippi was only completed in 1856, between Iowa and Illinois; prior to that time the only way to move goods across the river was by ferry. The oldest surviving bridge over the Mississippi is the Eads Bridge in St. Louis, which was completed in 1874 (seen here with a newer bridge in the background): The Eads Bridge proved to be a technical challenge, in part because of its length of almost 2 km and the novel (for the time) construction methods. Perhaps more significant was the thickness of the unconsolidated sediments at the bottom of the river. The support piers went some 30 m below the bottom of the river before hitting solid rock. Fifteen workers died from decompression sickness during construction of the bridge, working in pressurized caissons below the bottom of the river when the dangers of not properly decompressing were not understood.It's ironic that in the past rivers were such an impediment to movement, because until the invention of the railroad rivers were the only significant means of transporting large amounts of goods inland, and as a result they tend to have lots of people living nearby. Of the 20 most populous metropolitan areas in the United States, 15 are located either on the coast or on navigable rivers, and in many cases both (the exceptions are Dallas, Atlanta, Phoenix, Denver, and Orlando).In the same way that rivers have historically been an impediment to human travel, the dispersal of other organisms can be significantly affected by the presence of a large river. Consider this map of the distribution of the beech tree, Fagus grandifolia, from the USGS:

The Eads Bridge proved to be a technical challenge, in part because of its length of almost 2 km and the novel (for the time) construction methods. Perhaps more significant was the thickness of the unconsolidated sediments at the bottom of the river. The support piers went some 30 m below the bottom of the river before hitting solid rock. Fifteen workers died from decompression sickness during construction of the bridge, working in pressurized caissons below the bottom of the river when the dangers of not properly decompressing were not understood.It's ironic that in the past rivers were such an impediment to movement, because until the invention of the railroad rivers were the only significant means of transporting large amounts of goods inland, and as a result they tend to have lots of people living nearby. Of the 20 most populous metropolitan areas in the United States, 15 are located either on the coast or on navigable rivers, and in many cases both (the exceptions are Dallas, Atlanta, Phoenix, Denver, and Orlando).In the same way that rivers have historically been an impediment to human travel, the dispersal of other organisms can be significantly affected by the presence of a large river. Consider this map of the distribution of the beech tree, Fagus grandifolia, from the USGS: So, while rivers may no longer be a significant obstacle to my road trip, they are still a major factor when considering geologic, biologic, and cultural history.

So, while rivers may no longer be a significant obstacle to my road trip, they are still a major factor when considering geologic, biologic, and cultural history.

First obstacle-The Blue Ridge Escarpment

As I started my trip west out of Martinsville this morning, I almost immediately encountered my first geological obstacle of the trip - the Blue Ridge Escarpment, rising more than 400 m over just a few kilometers.Escarpments are steep slopes between two adjoining areas of different elevation. Martinsville is located near the western edge of Virginia's Piedmont physiographic province, and sits approximately 300 m above sea level. Traveling west on US 58, for the first 40 km the elevation only increases by about 100 m. But over the next 15 km the elevation increases by 450 m, a 10-fold increase in the average slope. Here's a photo from the top of the escarpment, looking back northeast toward the Piedmont:

As I started my trip west out of Martinsville this morning, I almost immediately encountered my first geological obstacle of the trip - the Blue Ridge Escarpment, rising more than 400 m over just a few kilometers.Escarpments are steep slopes between two adjoining areas of different elevation. Martinsville is located near the western edge of Virginia's Piedmont physiographic province, and sits approximately 300 m above sea level. Traveling west on US 58, for the first 40 km the elevation only increases by about 100 m. But over the next 15 km the elevation increases by 450 m, a 10-fold increase in the average slope. Here's a photo from the top of the escarpment, looking back northeast toward the Piedmont: And a similar view, taken on an earlier trip from further north in Floyd County:

And a similar view, taken on an earlier trip from further north in Floyd County: Escarpments often start as a fault that causes an elevation change, with the resulting slope eroding back over time. They can also form if there are rocks adjacent to each other that erode at different rates. But there is some debate about the origin of the Blue Ridge Escarpment. While there are lots of faults associated with the Piedmont and the Blue Ridge, the faults are mostly ancient, at least 200 million years old (although some eastern faults still show a fair amount of activity, as demonstrated by the Virginia earthquake of 2011). But a lithologic change is also not a good explanation, because the escarpment cuts across different rock types indiscriminately. There is evidence, however, that the escarpment is eroding back to the west, exposing the deeper Piedmont rocks in the process.The Blue Ridge Escarpment was a bit of a challenge for my fully-loaded truck towing a trailer, especially with the hairpin turns up the escarpment, but I was able to successfully reach the top and continue west.

Escarpments often start as a fault that causes an elevation change, with the resulting slope eroding back over time. They can also form if there are rocks adjacent to each other that erode at different rates. But there is some debate about the origin of the Blue Ridge Escarpment. While there are lots of faults associated with the Piedmont and the Blue Ridge, the faults are mostly ancient, at least 200 million years old (although some eastern faults still show a fair amount of activity, as demonstrated by the Virginia earthquake of 2011). But a lithologic change is also not a good explanation, because the escarpment cuts across different rock types indiscriminately. There is evidence, however, that the escarpment is eroding back to the west, exposing the deeper Piedmont rocks in the process.The Blue Ridge Escarpment was a bit of a challenge for my fully-loaded truck towing a trailer, especially with the hairpin turns up the escarpment, but I was able to successfully reach the top and continue west.

Headed west

For those of you that haven't been following me online (and hoping those who have will bear with me), I'd like to introduce myself. My name is Alton Dooley, and I'm a "museum person", a catch-all phrase for folks who have immersed themselves in various aspects of museum operations. I'm a paleontologist and geologist by training, but I've been working with and for museums for my entire adult life. Tomorrow, I begin driving west from Virginia to California to begin my new job as Executive Director of the Western Science Center.

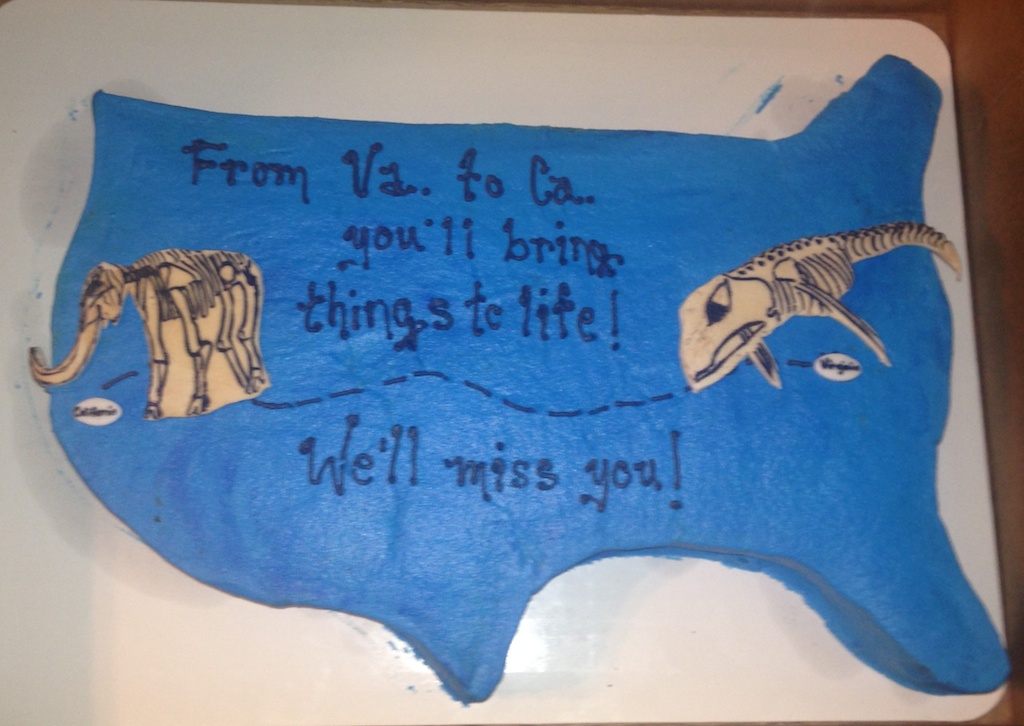

For those of you that haven't been following me online (and hoping those who have will bear with me), I'd like to introduce myself. My name is Alton Dooley, and I'm a "museum person", a catch-all phrase for folks who have immersed themselves in various aspects of museum operations. I'm a paleontologist and geologist by training, but I've been working with and for museums for my entire adult life. Tomorrow, I begin driving west from Virginia to California to begin my new job as Executive Director of the Western Science Center. For the last 15 years I've worked for the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville, Virginia (above). I initially worked for VMNH as an intern while I was still an undergraduate in the late 1980s, and in 1999, after completing my PhD, I was hired there as the Laboratory Manager for Paleontology and Earth Sciences. After several years I was promoted to Assistant Curator, and eventually became Curator of Paleontology, in charge of all of VMNH's fossil collections and paleontology-related activities.Even though I loved my job at VMNH, new opportunities have presented themselves on occasion, and when the Western Science Center offered me the position of director it was too good to pass up. And so I've spent the last month packing, getting my affairs at VMNH in order to ensure a smooth transition, and saying goodbye to coworkers, friends, and family:

For the last 15 years I've worked for the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville, Virginia (above). I initially worked for VMNH as an intern while I was still an undergraduate in the late 1980s, and in 1999, after completing my PhD, I was hired there as the Laboratory Manager for Paleontology and Earth Sciences. After several years I was promoted to Assistant Curator, and eventually became Curator of Paleontology, in charge of all of VMNH's fossil collections and paleontology-related activities.Even though I loved my job at VMNH, new opportunities have presented themselves on occasion, and when the Western Science Center offered me the position of director it was too good to pass up. And so I've spent the last month packing, getting my affairs at VMNH in order to ensure a smooth transition, and saying goodbye to coworkers, friends, and family: I'll be spending the next couple of weeks driving across the country and taking care of the myriad chores involved with relocating before I officially start in my new position. Which brings me to this blog...In September 2007 I began a blog called "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" to describe and promote the activities of my department at VMNH. Much to my surprise the blog was reasonably successful, and after 7 years and with 680 published posts "Updates" is one of the longest-running geoscience blogs in the world.While "Updates" was my creation, it is deeply intertwined with VMNH and so I decided not to try and adapt it to a new function. (Christina Byrd, the paleontology technician at VMNH, is going to continue writing posts for "Updates" so if you're a regular reader, have no fear!) Instead I decided to start a new blog with the Western Science Center specifically in mind.WSC is located near Diamond Valley, which is sometimes informally referred to as Valley of the Mastodons because of the large number of mastodon remains recovered there during the construction of the Diamond Valley Lake Reservoir. Those specimens are now housed at WSC, so "Valley of the Mastodon" seems a fitting name for this blog.I envision a variety of functions for "Valley of the Mastodon". In part I'll be announcing WSC events, new exhibits, guest speakers, etc. But I expect there will be an emphasis on the WSC collections, and on regional geology and paleontology. I spent a lot of my time at VMNH learning about the state's geology and paleontology, and really enjoyed sharing my discoveries on "Updates". So far I've spent a total of about 14 days in California, spread across 9 different cities. For me, California represents a whole new state to discover, and I hope to share what I learn with you on these pages.

I'll be spending the next couple of weeks driving across the country and taking care of the myriad chores involved with relocating before I officially start in my new position. Which brings me to this blog...In September 2007 I began a blog called "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" to describe and promote the activities of my department at VMNH. Much to my surprise the blog was reasonably successful, and after 7 years and with 680 published posts "Updates" is one of the longest-running geoscience blogs in the world.While "Updates" was my creation, it is deeply intertwined with VMNH and so I decided not to try and adapt it to a new function. (Christina Byrd, the paleontology technician at VMNH, is going to continue writing posts for "Updates" so if you're a regular reader, have no fear!) Instead I decided to start a new blog with the Western Science Center specifically in mind.WSC is located near Diamond Valley, which is sometimes informally referred to as Valley of the Mastodons because of the large number of mastodon remains recovered there during the construction of the Diamond Valley Lake Reservoir. Those specimens are now housed at WSC, so "Valley of the Mastodon" seems a fitting name for this blog.I envision a variety of functions for "Valley of the Mastodon". In part I'll be announcing WSC events, new exhibits, guest speakers, etc. But I expect there will be an emphasis on the WSC collections, and on regional geology and paleontology. I spent a lot of my time at VMNH learning about the state's geology and paleontology, and really enjoyed sharing my discoveries on "Updates". So far I've spent a total of about 14 days in California, spread across 9 different cities. For me, California represents a whole new state to discover, and I hope to share what I learn with you on these pages.