The Diamond Valley collection housed at WSC is an extremely rich record of Ice Age life in southern California, but it is far from the only Pleistocene site represented in the museum's collections.Right now, fossils of mammoths, camels, bison, horses, and other Ice Age megafauna from Joshua Tree National Park are on display in our "Fossils of Joshua Tree" exhibit. We are actively exploring new Pleistocene sites throughout Riverside County with colleagues from several institutions.In April, in conjunction with staff from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, we collected this large incomplete mammalian limb bone from Pleistocene deposits near Blythe. It has recently been prepared in our lab, so now ahead is the task of comparing it to other large Ice Age mammal fossils and determining what kind of animal it is. It might belong to a large Ice Age camel such as Camelops hesternus, the species also found at Diamond Valley, La Brea Tar Pits, and many other sites in North America. We have much more discover in southern California's Pleistocene.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

The Diamond Valley collection housed at WSC is an extremely rich record of Ice Age life in southern California, but it is far from the only Pleistocene site represented in the museum's collections.Right now, fossils of mammoths, camels, bison, horses, and other Ice Age megafauna from Joshua Tree National Park are on display in our "Fossils of Joshua Tree" exhibit. We are actively exploring new Pleistocene sites throughout Riverside County with colleagues from several institutions.In April, in conjunction with staff from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, we collected this large incomplete mammalian limb bone from Pleistocene deposits near Blythe. It has recently been prepared in our lab, so now ahead is the task of comparing it to other large Ice Age mammal fossils and determining what kind of animal it is. It might belong to a large Ice Age camel such as Camelops hesternus, the species also found at Diamond Valley, La Brea Tar Pits, and many other sites in North America. We have much more discover in southern California's Pleistocene.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsid jacket

Back in May, I shared the partial sacrum of a ceratopsid, a horned plant-eating dinosaur, from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.The Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society excavated four large plaster jackets from this site, containing vertebrae, ribs, and a hip bone of this partial skeleton. Earlier this week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began preparing another of these jackets, which contains the rest of the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae nestled between the right and left hip bones of the ceratopsid. In the image, just to the left of the Max scale bar, you can see a sequence of four fused vertebrae. Ceratopsids have around 10 sacral vertebrae, so these four coupled with the five from the other jacket that I posted about in May mean that we probably have almost the entire sacrum. Opening each new jacket reveals more about this relative of Triceratops that lived 79 million years ago.

Earlier this week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began preparing another of these jackets, which contains the rest of the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae nestled between the right and left hip bones of the ceratopsid. In the image, just to the left of the Max scale bar, you can see a sequence of four fused vertebrae. Ceratopsids have around 10 sacral vertebrae, so these four coupled with the five from the other jacket that I posted about in May mean that we probably have almost the entire sacrum. Opening each new jacket reveals more about this relative of Triceratops that lived 79 million years ago.

Fossil Friday - Foerestephyllum

Corals are such an iconic part of the modern ocean, it's easy to overlook the fact that they didn't become widespread until the Ordovician Period, 4 billion years after the Earth formed and some 30 million years after the Cambrian Explosion.The coral shown above is Foerstephyllum, and example of a tabulate coral. The Tabulata are one of the two common types of fossil corals in the Paleozoic Era, along with the Rugosa. Of course, an important reason these groups are common as fossils is because they made large calcite structures that preserve very well. At least in the modern ocean, there are many soft-bodied corals that would be much less likely to fossilize, and that may have been the case in the past as well.This Foerstephyllum head comes from the Drakes Formation near Bardstown, Kentucky. There is a layer within this unit that is made mostly of large coral heads:

Corals are such an iconic part of the modern ocean, it's easy to overlook the fact that they didn't become widespread until the Ordovician Period, 4 billion years after the Earth formed and some 30 million years after the Cambrian Explosion.The coral shown above is Foerstephyllum, and example of a tabulate coral. The Tabulata are one of the two common types of fossil corals in the Paleozoic Era, along with the Rugosa. Of course, an important reason these groups are common as fossils is because they made large calcite structures that preserve very well. At least in the modern ocean, there are many soft-bodied corals that would be much less likely to fossilize, and that may have been the case in the past as well.This Foerstephyllum head comes from the Drakes Formation near Bardstown, Kentucky. There is a layer within this unit that is made mostly of large coral heads: This bed is close to the top of the Ordovician; in fact, the massive rocks visible in the upper left corner are Silurian, although I think there is an unconformity between them.Tabulate corals remained as significant reef-builders up to the end of the Paleozoic Era. They went extinct, along with the rugose corals and about 90% or more of all marine species, in the devastating mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period.This specimen of Foerstephyllum is currently on display at the Western Science Center in the "Life in the Ancient Seas" exhibit, and a 3D model is available for viewing and download on SketchFab at https://skfb.ly/6NtRI.

This bed is close to the top of the Ordovician; in fact, the massive rocks visible in the upper left corner are Silurian, although I think there is an unconformity between them.Tabulate corals remained as significant reef-builders up to the end of the Paleozoic Era. They went extinct, along with the rugose corals and about 90% or more of all marine species, in the devastating mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period.This specimen of Foerstephyllum is currently on display at the Western Science Center in the "Life in the Ancient Seas" exhibit, and a 3D model is available for viewing and download on SketchFab at https://skfb.ly/6NtRI.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsid ilium

On May 17, I posted a photo of the ilium of a ceratopsid dinosaur that we collected in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. At the time, only the medial surface of the bone was visible; however, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working hard and has now prepped the lateral surface as well. On May 17, I identified the bone as a left ilium, but now that I can see the whole thing, I can say that it's actually a right ilium.This beautifully-preserved ilium is part of an incomplete skeleton that also includes vertebrae and ribs from the torso, as well as the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae to which this ilium would have attached. Ceratopsids, the great horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops, were very abundant and diverse in western North America during the Late Cretaceous; our specimen is around 79 million years old, and we can't yet determine what species it represents. This skeleton was collected in 2016-2018 by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

On May 17, I posted a photo of the ilium of a ceratopsid dinosaur that we collected in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. At the time, only the medial surface of the bone was visible; however, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working hard and has now prepped the lateral surface as well. On May 17, I identified the bone as a left ilium, but now that I can see the whole thing, I can say that it's actually a right ilium.This beautifully-preserved ilium is part of an incomplete skeleton that also includes vertebrae and ribs from the torso, as well as the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae to which this ilium would have attached. Ceratopsids, the great horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops, were very abundant and diverse in western North America during the Late Cretaceous; our specimen is around 79 million years old, and we can't yet determine what species it represents. This skeleton was collected in 2016-2018 by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Back from Field Work

The first part of the Western Science Center's summer field season with Zuni Dinosaur Institute for the Geosciences and the Southwest Paleontological Society is now over, and that means lots of new fossils have been brought to the museum!

The first part of the Western Science Center's summer field season with Zuni Dinosaur Institute for the Geosciences and the Southwest Paleontological Society is now over, and that means lots of new fossils have been brought to the museum! WSC staff and volunteers have spent the last two weeks out in New Mexico's Menefee Formation, where new species like Invictarx zephyri and the theropod Dynamoterror dynastes were discovered. A literal ton of fossil jackets have been unloaded into the museum, and we'll now spend the foreseeable future getting our new specimens ready for research, outreach, and exhibition.

WSC staff and volunteers have spent the last two weeks out in New Mexico's Menefee Formation, where new species like Invictarx zephyri and the theropod Dynamoterror dynastes were discovered. A literal ton of fossil jackets have been unloaded into the museum, and we'll now spend the foreseeable future getting our new specimens ready for research, outreach, and exhibition.![fieldwork4]](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c7dbcb0e666693012e253e8/5e06577dccb29d33b46f6433/5e0657d2ccb29d33b46f86bf/1577474002689/fieldwork4.jpg?format=original) So what have we found? That's still being determined - though we know much of the material includes more dinosaurs. The Menefee Formation is part of the Late Cretaceous and is approximately 80 million years old. This span of time is not particularly well understood, and we hope that our work in the area will continue to shed light on this period!

So what have we found? That's still being determined - though we know much of the material includes more dinosaurs. The Menefee Formation is part of the Late Cretaceous and is approximately 80 million years old. This span of time is not particularly well understood, and we hope that our work in the area will continue to shed light on this period! We'll sharing much more about these fossils in the coming weeks - stay tuned for more!Post by Brittney Stoneburg.

We'll sharing much more about these fossils in the coming weeks - stay tuned for more!Post by Brittney Stoneburg.

Fossil Friday - Miocene horses

Hello! I'm Brittney Stoneburg, the Marketing and Events Specialist for the Western Science Center. While my job mostly entails communications and outreach at the museum, I've spent the last year dipping my toes into research! For my first research project, I've been working on fossils collected by the Western Science Center from our field site in San Bernardino National Forest. This means I'm up to my neck in horse teeth right now! I've been focusing on the small, three toed horses that roamed Southern California during the early to middle Miocene, approximately 18 million years ago.

For my first research project, I've been working on fossils collected by the Western Science Center from our field site in San Bernardino National Forest. This means I'm up to my neck in horse teeth right now! I've been focusing on the small, three toed horses that roamed Southern California during the early to middle Miocene, approximately 18 million years ago. Multiple species of horse lived in this area, including Scaphohippus, whose teeth are picture above. While our collection from this site has only a few post-cranial bits, we can make pretty solid identifications just from the teeth. Horse teeth like these have numerous features that make it possible to identify them down to the species level. Knowing what horses lived in this area during the Miocene can tell us a lot not only about the horses themselves, but about the environment they lived in!I'll be presenting on my research at the North American Paleontological Conference in June, so if you'll be there, feel free to ask me about all of these horses!

Multiple species of horse lived in this area, including Scaphohippus, whose teeth are picture above. While our collection from this site has only a few post-cranial bits, we can make pretty solid identifications just from the teeth. Horse teeth like these have numerous features that make it possible to identify them down to the species level. Knowing what horses lived in this area during the Miocene can tell us a lot not only about the horses themselves, but about the environment they lived in!I'll be presenting on my research at the North American Paleontological Conference in June, so if you'll be there, feel free to ask me about all of these horses!

Fossil Friday - ceratopsid illium

Last week for Fossil Friday, I posted the sacrum of a ceratopsid, a large horned dinosaur related to Triceratops. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hip bones attach. Today, I want to show you one of those hip bones from the same ceratopsid individual. This is the left ilium, showing the inner surface where it would have attached to the sacral ribs along a series of deep facets. At about 80 centimeters long, this ilium is not terribly big for a ceratopsid, but it still would have been a hefty animal, plodding around the forests and swamps of Late Cretaceous New Mexico.In the coming months, we will create 3D-printed replicas of the sacrum and ilium of this ceratopsid to see how they fit together, the first step in rebuilding this 79-million-year-old skeleton. We also have several vertebrae and ribs from the back. This specimen was collected during the 2017 and 2018 field seasons by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. The sacrum and ilium have both been prepped by WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Last week for Fossil Friday, I posted the sacrum of a ceratopsid, a large horned dinosaur related to Triceratops. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hip bones attach. Today, I want to show you one of those hip bones from the same ceratopsid individual. This is the left ilium, showing the inner surface where it would have attached to the sacral ribs along a series of deep facets. At about 80 centimeters long, this ilium is not terribly big for a ceratopsid, but it still would have been a hefty animal, plodding around the forests and swamps of Late Cretaceous New Mexico.In the coming months, we will create 3D-printed replicas of the sacrum and ilium of this ceratopsid to see how they fit together, the first step in rebuilding this 79-million-year-old skeleton. We also have several vertebrae and ribs from the back. This specimen was collected during the 2017 and 2018 field seasons by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. The sacrum and ilium have both been prepped by WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian sacrum

Horned dinosaurs were one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of western North America. Known as ceratopsids, these rhino- to elephant-sized beasts brandished horns, spikes, and frills on their massive skulls. More than 40 different species are known to have inhabited western North America at different points in time between 80 and 66 million years ago. The last of them was the great "three-horned face" - Triceratops.Ceratopsids have been known from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico since the 1990s, when paleontologists at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science reported fossils including a partial skeleton. More recent expeditions to the Menefee by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society have discovered further ceratopsid fossils, including another partial skeleton now being prepped at WSC.Today's image is the sacrum of that 79-million-year-old ceratopsid skeleton, recently prepped by WSC volunteer Joe Reavis. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hips were attached. In the image, the bottom surface of the bone is visible. We'll be working on more bones from this skeleton over the coming months, including a hip bone, more vertebrae, and ribs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Horned dinosaurs were one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of western North America. Known as ceratopsids, these rhino- to elephant-sized beasts brandished horns, spikes, and frills on their massive skulls. More than 40 different species are known to have inhabited western North America at different points in time between 80 and 66 million years ago. The last of them was the great "three-horned face" - Triceratops.Ceratopsids have been known from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico since the 1990s, when paleontologists at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science reported fossils including a partial skeleton. More recent expeditions to the Menefee by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society have discovered further ceratopsid fossils, including another partial skeleton now being prepped at WSC.Today's image is the sacrum of that 79-million-year-old ceratopsid skeleton, recently prepped by WSC volunteer Joe Reavis. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hips were attached. In the image, the bottom surface of the bone is visible. We'll be working on more bones from this skeleton over the coming months, including a hip bone, more vertebrae, and ribs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - fern

Over the last year or so, I've posted many bones from large herbivorous dinosaurs that lived in New Mexico around 79 million years ago, such as duck-billed hadrosaurs, horned ceratopsids, and the armored Invictarx.Alongside the bones of these beasts in the Menefee Formation we often find fossil plants. Many of these occurrences are petrified logs and stumps, which we find eroding out onto the surface.However, sometimes when we dig into the layers of mudstone to excavate dinosaur bones, we also encounter beautiful fossil leaves. The image today is a very nice leaf from a Late Cretaceous fern, probably belonging to the living fern genus Anemia. Fossils like this give us some idea of what the plant-eating dinosaurs might have been eating, and show that back then New Mexico was a much wetter habitat than today. It was a muddy floodplain lush with plants and teeming with dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Over the last year or so, I've posted many bones from large herbivorous dinosaurs that lived in New Mexico around 79 million years ago, such as duck-billed hadrosaurs, horned ceratopsids, and the armored Invictarx.Alongside the bones of these beasts in the Menefee Formation we often find fossil plants. Many of these occurrences are petrified logs and stumps, which we find eroding out onto the surface.However, sometimes when we dig into the layers of mudstone to excavate dinosaur bones, we also encounter beautiful fossil leaves. The image today is a very nice leaf from a Late Cretaceous fern, probably belonging to the living fern genus Anemia. Fossils like this give us some idea of what the plant-eating dinosaurs might have been eating, and show that back then New Mexico was a much wetter habitat than today. It was a muddy floodplain lush with plants and teeming with dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Mistaken Identity

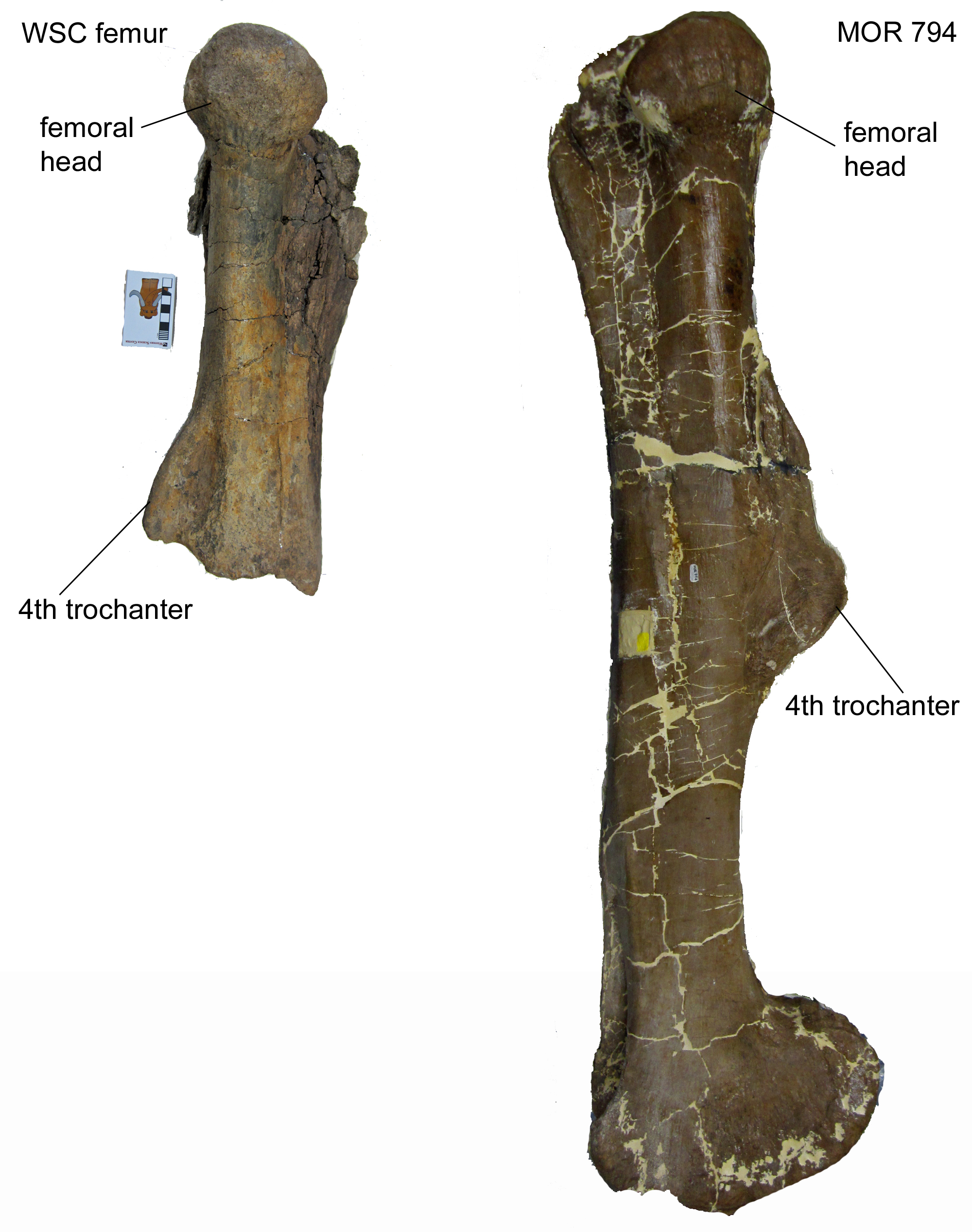

On March 8 Fossil Friday, I posted an 80-million-year-old dinosaur bone from New Mexico, which I identified as a tibia (shin bone). At the time, it was only partially prepped, and since then, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working tirelessly to remove the remaining mudstone.It turns out the "tibia" is actually a femur! It's the proximal half of the left femur of a hadrosaur, one of the large duck-billed plant-eating dinosaurs that are so abundant in Upper Cretaceous rocks throughout the American West. Comparison with a complete hadrosaur femur from Montana (Museum of the Rockies specimen MOR 794) allows us to identify several major features, including the head that fitted into the hip socket and the 4th trochanter, a major muscle attachment site. It also shows that the WSC femur is from a fairly large individual, probably close to 30 feet long.Hadrosaur bones are very common in the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which this femur was collected by my colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We'll have more to say in the near future.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

On March 8 Fossil Friday, I posted an 80-million-year-old dinosaur bone from New Mexico, which I identified as a tibia (shin bone). At the time, it was only partially prepped, and since then, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working tirelessly to remove the remaining mudstone.It turns out the "tibia" is actually a femur! It's the proximal half of the left femur of a hadrosaur, one of the large duck-billed plant-eating dinosaurs that are so abundant in Upper Cretaceous rocks throughout the American West. Comparison with a complete hadrosaur femur from Montana (Museum of the Rockies specimen MOR 794) allows us to identify several major features, including the head that fitted into the hip socket and the 4th trochanter, a major muscle attachment site. It also shows that the WSC femur is from a fairly large individual, probably close to 30 feet long.Hadrosaur bones are very common in the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which this femur was collected by my colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We'll have more to say in the near future.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - dinosaur tibia

We have discovered many isolated dinosaur limb bones in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. Although it's difficult to infer the full appearance of a dinosaur from a single bone, even isolated bones can tell us a great deal about what kinds of dinosaurs were roaming around 80 million years ago, and can be very surprising!This bone was collected by my colleagues at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and volunteers with the Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We have been thinking that it was possibly two dinosaur limb bones next to each other. However, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis opened up the plaster jacket this week, and it turns out that it contains a single massive shin bone, a tibia. The bone is still partially encased in mudstone, but we'll keep working on it to determine what sort of dinosaur walked around on this immensely thick bone.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

We have discovered many isolated dinosaur limb bones in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. Although it's difficult to infer the full appearance of a dinosaur from a single bone, even isolated bones can tell us a great deal about what kinds of dinosaurs were roaming around 80 million years ago, and can be very surprising!This bone was collected by my colleagues at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and volunteers with the Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We have been thinking that it was possibly two dinosaur limb bones next to each other. However, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis opened up the plaster jacket this week, and it turns out that it contains a single massive shin bone, a tibia. The bone is still partially encased in mudstone, but we'll keep working on it to determine what sort of dinosaur walked around on this immensely thick bone.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - dinosaur limb bone

In the Western Science Center lab, we're making steady progress through several field seasons' worth of fossils from the Menefee Formation in New Mexico. We're working on fossils of dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and plants, all dating to around 80 million years ago.This week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began prepping a fairly hefty dinosaur limb bone that was collected in 2016 by me and colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. We're not yet certain what type of dinosaur this is from, or even which bone in the skeleton this is. One of the ends of the bone had eroded out onto the hillside prior to discovery, so we need to see if we can piece it back together and reattach it to the rest of the bone. There's always more to learn!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

In the Western Science Center lab, we're making steady progress through several field seasons' worth of fossils from the Menefee Formation in New Mexico. We're working on fossils of dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and plants, all dating to around 80 million years ago.This week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began prepping a fairly hefty dinosaur limb bone that was collected in 2016 by me and colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. We're not yet certain what type of dinosaur this is from, or even which bone in the skeleton this is. One of the ends of the bone had eroded out onto the hillside prior to discovery, so we need to see if we can piece it back together and reattach it to the rest of the bone. There's always more to learn!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian vertebra

On January 25, I showed you a horned dinosaur vertebra that was still partially encased in its plaster field jacket. Western Science Center volunteer John Deleon has been working hard on this vertebra for the last several weeks and has made great progress. The vertebra is now completely freed from its jacket, and is awaiting a bit more matrix removal and gluing before it is finished.This vertebra is part of a partial ceratopsian skeleton excavated in New Mexico in 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. At between 80 and 79 million years old, this skeleton is among the oldest specimens of large horned dinosaurs from North America. We are not yet certain what kind of horned dinosaur this is, but there are numerous more bones from the same animal waiting to be prepared in the WSC lab.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

On January 25, I showed you a horned dinosaur vertebra that was still partially encased in its plaster field jacket. Western Science Center volunteer John Deleon has been working hard on this vertebra for the last several weeks and has made great progress. The vertebra is now completely freed from its jacket, and is awaiting a bit more matrix removal and gluing before it is finished.This vertebra is part of a partial ceratopsian skeleton excavated in New Mexico in 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. At between 80 and 79 million years old, this skeleton is among the oldest specimens of large horned dinosaurs from North America. We are not yet certain what kind of horned dinosaur this is, but there are numerous more bones from the same animal waiting to be prepared in the WSC lab.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday -crocodile skull

For Fossil Friday today, I want to give you an update on one of the fossils we collected in New Mexico last year. On December 14, 2018, I posted the smashed up skull of a small crocodile from the Menefee Formation, around 79 million years old.At the time, we had just removed this little skull from its plaster jacket. Although broken apart by erosion, from the deeply pitted texture of the bones and presence of the occipital condyle (the ball at the back of the skull that articulates with the first neck vertebra), it was clear that this is indeed a small crocodile skull. In order to piece it back together, the bone fragments would need to be removed from the surrounding rock. However, it appeared that none of the fragments had moved too far from their original positions. Therefore, it was important to have a record of the condition of the fossil before preparation began.To that end, WSC Educator Brett Dooley scanned the fossil with our NextEngine laser scanner, and Director Alton Dooley created a digital 3D model. We then printed it on one of the museum's 3D printers. We also took photographs of the fossil. Using the printed replica and photos as a guide, WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis has been teasing the bone fragments from the rock in order to clean them and fit them together. As of now, the mass of bone fragments has been disassembled, and Joe and I have been able to start fitting pieces together and identifying the bones.The bones represent much of the back end of the skull, including bones that surrounded the brain (parietal, basisphenoid, and basioccipital with the occipital condyle), bones from the adjacent skull roof (left squamosal), and the bones with which the lower jaw would have articulated (the left and right quadrates). There is much work still to do, but once finished, this little skull will be a nice addition to our knowledge of the Menefee Formation's crocodiles. We hope to be able to reconstruct this region of the skull and determine to which species this specimen belongs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

For Fossil Friday today, I want to give you an update on one of the fossils we collected in New Mexico last year. On December 14, 2018, I posted the smashed up skull of a small crocodile from the Menefee Formation, around 79 million years old.At the time, we had just removed this little skull from its plaster jacket. Although broken apart by erosion, from the deeply pitted texture of the bones and presence of the occipital condyle (the ball at the back of the skull that articulates with the first neck vertebra), it was clear that this is indeed a small crocodile skull. In order to piece it back together, the bone fragments would need to be removed from the surrounding rock. However, it appeared that none of the fragments had moved too far from their original positions. Therefore, it was important to have a record of the condition of the fossil before preparation began.To that end, WSC Educator Brett Dooley scanned the fossil with our NextEngine laser scanner, and Director Alton Dooley created a digital 3D model. We then printed it on one of the museum's 3D printers. We also took photographs of the fossil. Using the printed replica and photos as a guide, WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis has been teasing the bone fragments from the rock in order to clean them and fit them together. As of now, the mass of bone fragments has been disassembled, and Joe and I have been able to start fitting pieces together and identifying the bones.The bones represent much of the back end of the skull, including bones that surrounded the brain (parietal, basisphenoid, and basioccipital with the occipital condyle), bones from the adjacent skull roof (left squamosal), and the bones with which the lower jaw would have articulated (the left and right quadrates). There is much work still to do, but once finished, this little skull will be a nice addition to our knowledge of the Menefee Formation's crocodiles. We hope to be able to reconstruct this region of the skull and determine to which species this specimen belongs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur metatarsal

Discovering a dinosaur skeleton is a rare and special event.Most often, when out exploring in the badlands of New Mexico, we find isolated bones. However, even an isolated bone offers a wealth of information, about what kinds of animals were living in the area 79 million years ago, the depositional environment, and any unusual anatomical features or pathologies. Every summer, we collect numerous isolated bones of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and other animals from the Menefee Formation.Western Science Center prep lab volunteer John Deleon recently began preparing this dinosaur bone, which was collected by Southwest Paleontological Society volunteers Ben Mohler and Jake Kudlinski during our expedition last June. No other bones were found nearby, but this bone itself is well preserved and certainly worthy of the effort and study. It is a metatarsal, one of the large foot bones situated between the ankle and the toes, and probably belonged to a duck-billed plant-eating hadrosaur. Isolated hadrosaur bones, mostly limb bones and vertebrae, are the most commonly found dinosaur fossils in the Menefee Formation, suggesting that hadrosaurs probably were quite abundant in the ancient ecosystem. We'll be able to compare this bone to other limb bones we have collected over the years.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Discovering a dinosaur skeleton is a rare and special event.Most often, when out exploring in the badlands of New Mexico, we find isolated bones. However, even an isolated bone offers a wealth of information, about what kinds of animals were living in the area 79 million years ago, the depositional environment, and any unusual anatomical features or pathologies. Every summer, we collect numerous isolated bones of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and other animals from the Menefee Formation.Western Science Center prep lab volunteer John Deleon recently began preparing this dinosaur bone, which was collected by Southwest Paleontological Society volunteers Ben Mohler and Jake Kudlinski during our expedition last June. No other bones were found nearby, but this bone itself is well preserved and certainly worthy of the effort and study. It is a metatarsal, one of the large foot bones situated between the ankle and the toes, and probably belonged to a duck-billed plant-eating hadrosaur. Isolated hadrosaur bones, mostly limb bones and vertebrae, are the most commonly found dinosaur fossils in the Menefee Formation, suggesting that hadrosaurs probably were quite abundant in the ancient ecosystem. We'll be able to compare this bone to other limb bones we have collected over the years.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Zygolophodon tooth

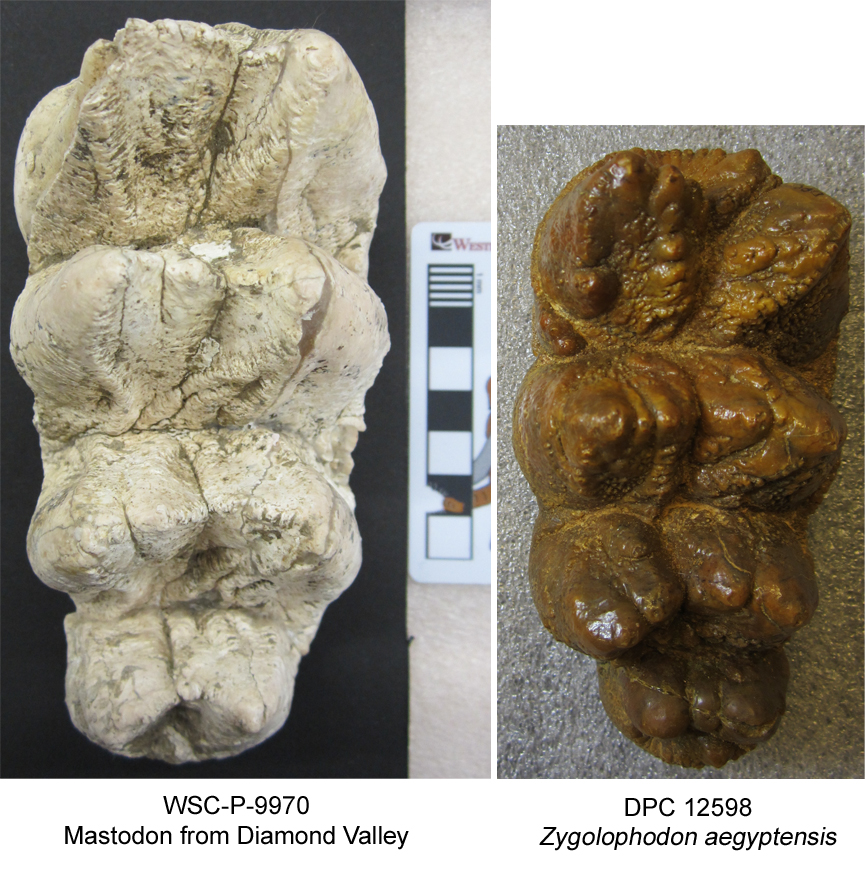

Last week, I visited the Division of Fossil Primates at the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina. They have a great collection of fossil proboscideans from Egypt, including early forms like Moeritherium and Paleomastodon, as well as later, larger species such as Gomphotherium angustidens.I was there especially to see four teeth, the only known fossils of Zygolophodon aegyptensis. The genus Zygolophodon is long-lived and widespread, including many other species from Europe, Asia, and North America. At about 18 million years old, Z. aegyptensis is among the oldest. Zygolophodon is a member of the group Mammutidae, making it a close relative of North America's mastodons, including those found at Diamond Valley and housed at Western Science Center.The image here is DPC 12598, an upper molar (right M3) of Zygolophodon aegyptensis, and a left M3 of a mastodon from Diamond Valley (WSC-P-9970) set to the same scale. My Western Science Center colleagues and I are working with paleontologists at several other institutions to explore the whole evolutionary history of Mammutidae. Visiting other museums to examine fossils of other species and comparing them to the bounty of mastodons from Diamond Valley is one of the first steps on this journey.My thanks to Catherine Riddle of the Division of Fossil Primates for her assistance during my visit.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Last week, I visited the Division of Fossil Primates at the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina. They have a great collection of fossil proboscideans from Egypt, including early forms like Moeritherium and Paleomastodon, as well as later, larger species such as Gomphotherium angustidens.I was there especially to see four teeth, the only known fossils of Zygolophodon aegyptensis. The genus Zygolophodon is long-lived and widespread, including many other species from Europe, Asia, and North America. At about 18 million years old, Z. aegyptensis is among the oldest. Zygolophodon is a member of the group Mammutidae, making it a close relative of North America's mastodons, including those found at Diamond Valley and housed at Western Science Center.The image here is DPC 12598, an upper molar (right M3) of Zygolophodon aegyptensis, and a left M3 of a mastodon from Diamond Valley (WSC-P-9970) set to the same scale. My Western Science Center colleagues and I are working with paleontologists at several other institutions to explore the whole evolutionary history of Mammutidae. Visiting other museums to examine fossils of other species and comparing them to the bounty of mastodons from Diamond Valley is one of the first steps on this journey.My thanks to Catherine Riddle of the Division of Fossil Primates for her assistance during my visit.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - crocodile skull

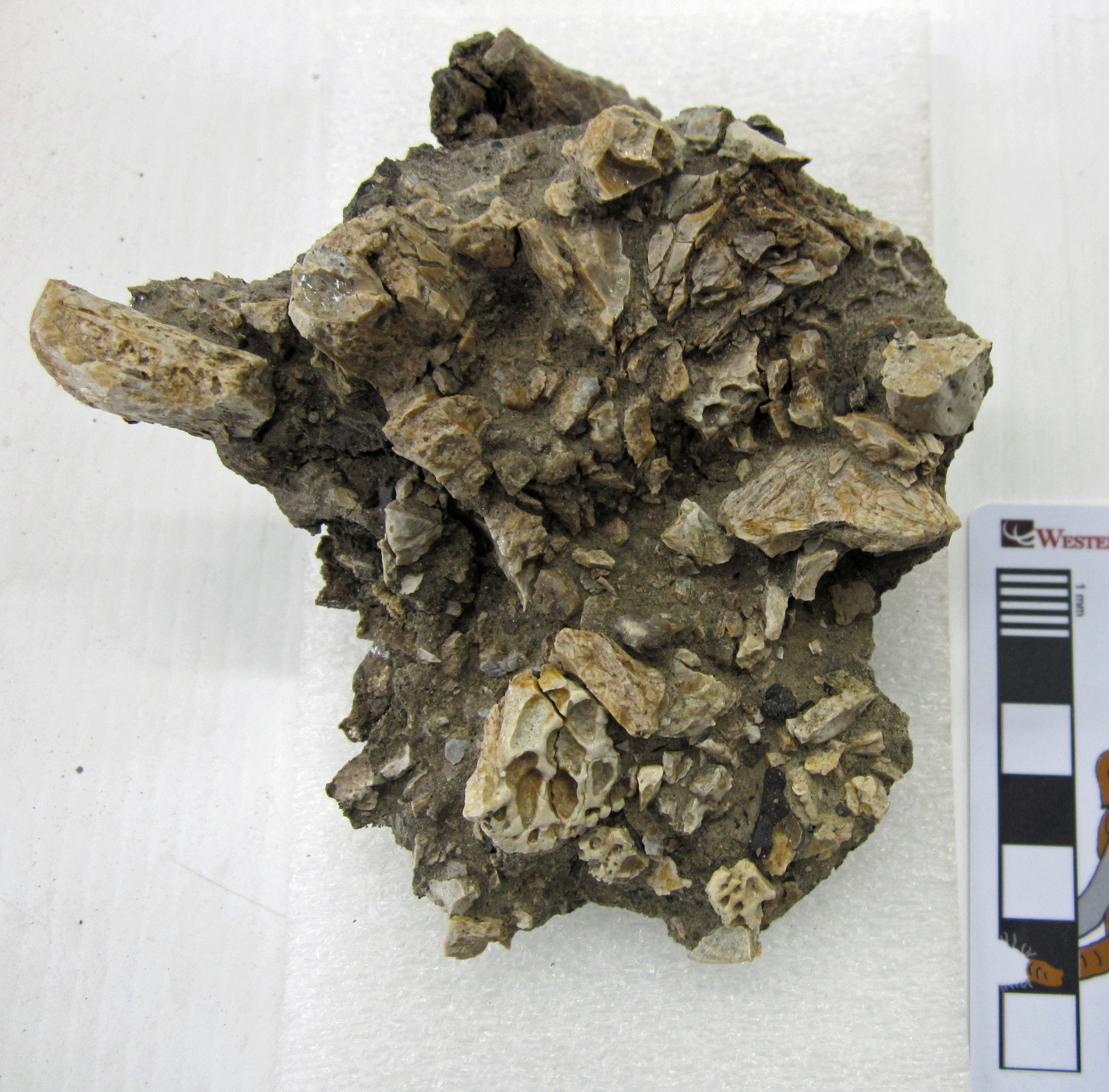

Giant reptiles abound in our field area in New Mexico. Big dinosaurs like Invictarx, Dynamoterror, and the hadrosaur we're working on now; hefty crocodiles; and even sizable turtles are the most commonly found animals in the 79-million-year-old rocks of the Menefee Formation. Fossils of small creatures are comparatively rare, and skull material for any animal is pretty thin on the ground as well.During the expedition in May with our partners at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, three volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society collected a small mass of bone with a distinctive heavily pitted texture that resembles modern crocodilian skulls. In the field, we tentatively identified it as part of a crocodilian skull. We opened up the little plaster jacket here at Western Science Center this week, and confirmed that it is indeed the partial skull of a small crocodilian. The dorsal surface of the skull is badly fragmented, but clearly shows that pitted texture. The ventral side is also highly weathered, but we can see the base of the braincase and the occipital condyle, the ball at the back of the skull that articulates with the first neck vertebra.

Giant reptiles abound in our field area in New Mexico. Big dinosaurs like Invictarx, Dynamoterror, and the hadrosaur we're working on now; hefty crocodiles; and even sizable turtles are the most commonly found animals in the 79-million-year-old rocks of the Menefee Formation. Fossils of small creatures are comparatively rare, and skull material for any animal is pretty thin on the ground as well.During the expedition in May with our partners at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, three volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society collected a small mass of bone with a distinctive heavily pitted texture that resembles modern crocodilian skulls. In the field, we tentatively identified it as part of a crocodilian skull. We opened up the little plaster jacket here at Western Science Center this week, and confirmed that it is indeed the partial skull of a small crocodilian. The dorsal surface of the skull is badly fragmented, but clearly shows that pitted texture. The ventral side is also highly weathered, but we can see the base of the braincase and the occipital condyle, the ball at the back of the skull that articulates with the first neck vertebra. We're just beginning to prep this fossil. Right now, based on the size and skull texture, it might belong to an ancient alligator relative called Brachychampsa. Brachychampsa is known from many Upper Cretaceous formations in western North America, and was first identified in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico by paleontologist Tom Williamson (New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science) in 1996. It's a small animal, just about six feet long, with a broad, blunt snout, as you can see on this mounted skeleton that I photographed at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City. We'll have much more to say about our little skull and the other Menefee crocodilians in the not too distant future.

We're just beginning to prep this fossil. Right now, based on the size and skull texture, it might belong to an ancient alligator relative called Brachychampsa. Brachychampsa is known from many Upper Cretaceous formations in western North America, and was first identified in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico by paleontologist Tom Williamson (New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science) in 1996. It's a small animal, just about six feet long, with a broad, blunt snout, as you can see on this mounted skeleton that I photographed at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City. We'll have much more to say about our little skull and the other Menefee crocodilians in the not too distant future. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - dinosaur jacket

The fossil prep lab at Western Science Center is abuzz these days (literally, when the air scribes are blasting away). WSC staff and volunteers are working their way through the half-ton of fossils we brought back to the museum last summer from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.Much of our recent prep effort has focused on the hadrosaur skeleton I posted about back in September and October. We're now moving on to some of the smaller items we brought back.One of the new sites we documented and collected during the 2018 field season is a scatter of at least half a dozen dinosaur bones, discovered by WSC volunteer John DeLeon. Although the bones are highly weathered, we collected them all and got them safely back to the museum. Given their close association at the field site and the absence of any other fossil organisms, these bones probably all belong to the same individual dinosaur. John opened up the largest plaster jacket from the site yesterday. There is a little knob of bone exposed to the left in the image; the rest of the bone is underneath the fossilized tree branch to the right. We don't know what type of dinosaur is represented by these bones, but hopefully the answer will emerge as John continues his work.This specimen and all the Menefee fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

The fossil prep lab at Western Science Center is abuzz these days (literally, when the air scribes are blasting away). WSC staff and volunteers are working their way through the half-ton of fossils we brought back to the museum last summer from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.Much of our recent prep effort has focused on the hadrosaur skeleton I posted about back in September and October. We're now moving on to some of the smaller items we brought back.One of the new sites we documented and collected during the 2018 field season is a scatter of at least half a dozen dinosaur bones, discovered by WSC volunteer John DeLeon. Although the bones are highly weathered, we collected them all and got them safely back to the museum. Given their close association at the field site and the absence of any other fossil organisms, these bones probably all belong to the same individual dinosaur. John opened up the largest plaster jacket from the site yesterday. There is a little knob of bone exposed to the left in the image; the rest of the bone is underneath the fossilized tree branch to the right. We don't know what type of dinosaur is represented by these bones, but hopefully the answer will emerge as John continues his work.This specimen and all the Menefee fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Squalodon whitmorei

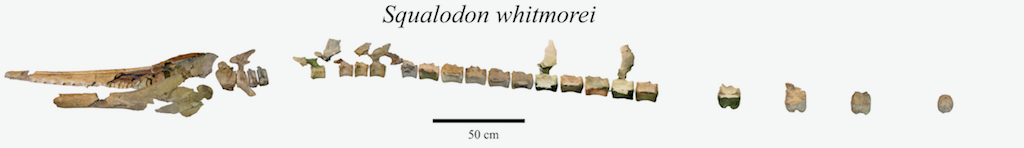

Usually we use our Fossil Friday posts to talk about specimens that are housed in the WSC collections. But today I'm going to talk about our newest 3D print, the skull of the primitive toothed whale Squalodon whitmorei.Squalodonts are a family of toothed whales that lived in the Oligocene and the first half of the Miocene. At one time it was thought they might be close to the transition between Eocene archaeocete whales and modern dolphins and other toothed cetaceans. It turns out they were their own specialized branch of toothed whales, members of a once widespread group called the platanistoids that has since been mostly supplanted by the delphinoids. They have a somewhat primitive look largely because of their extremely heterodont teeth, including serrated, triangular back teeth (hence the name Squalodon, which literally means "shark tooth"). They were among the last groups of cetaceans (maybe THE last group) to retain these triangular, double-rooted back teeth. They are best known from Europe and eastern North America, but examples have been found all over the world.This specimen holds a special place for me, because it was the first fossil vertebrate I ever had the chance to work on. In 1989 I traveled to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to talk about possible research topics for my senior thesis at Carleton College. I met paleontologists Clayton Ray, Frank Whitmore, and Dave Bohaska while I was there, and after a day of looking at fossils they suggested that if I wanted to I could come back next summer and work on squalodont whales for my thesis (a group I had never heard of before).The next summer, after securing free housing from a Carleton alumnus, Frank turned over to me several boxes of bone fragments that had been collected by a boy scout troop in Virginia in the 1970s. I spent the next 2 months learning techniques for cleaning and repairing fossils, while Frank tutored my on cetacean anatomy. By the end of the summer I had put together one of the most complete known skeletons of Squalodon, the largest example of the genus ever found:

Usually we use our Fossil Friday posts to talk about specimens that are housed in the WSC collections. But today I'm going to talk about our newest 3D print, the skull of the primitive toothed whale Squalodon whitmorei.Squalodonts are a family of toothed whales that lived in the Oligocene and the first half of the Miocene. At one time it was thought they might be close to the transition between Eocene archaeocete whales and modern dolphins and other toothed cetaceans. It turns out they were their own specialized branch of toothed whales, members of a once widespread group called the platanistoids that has since been mostly supplanted by the delphinoids. They have a somewhat primitive look largely because of their extremely heterodont teeth, including serrated, triangular back teeth (hence the name Squalodon, which literally means "shark tooth"). They were among the last groups of cetaceans (maybe THE last group) to retain these triangular, double-rooted back teeth. They are best known from Europe and eastern North America, but examples have been found all over the world.This specimen holds a special place for me, because it was the first fossil vertebrate I ever had the chance to work on. In 1989 I traveled to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to talk about possible research topics for my senior thesis at Carleton College. I met paleontologists Clayton Ray, Frank Whitmore, and Dave Bohaska while I was there, and after a day of looking at fossils they suggested that if I wanted to I could come back next summer and work on squalodont whales for my thesis (a group I had never heard of before).The next summer, after securing free housing from a Carleton alumnus, Frank turned over to me several boxes of bone fragments that had been collected by a boy scout troop in Virginia in the 1970s. I spent the next 2 months learning techniques for cleaning and repairing fossils, while Frank tutored my on cetacean anatomy. By the end of the summer I had put together one of the most complete known skeletons of Squalodon, the largest example of the genus ever found:

After successfully defending my undergraduate thesis, I enrolled in graduate school at LSU, and continued my work on squalodonts. This skeleton, along with an additional skull discovered in Virginia in the 1990's, became the main subjects in Chapter 4 of my doctoral dissertation.After completing my doctorate I accepted a position at VMNH, and spent some of my time finishing up projects I had started in graduate school. Finally, in 2005 I formally published "A new species of Squalodon (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Miocene of eastern North America". That paper established the new species Squalodon whitmorei (named in honor of Frank Whitmore), with this specimen as the holotype.As it turns out, in 2019 and 2020 Western Science Center will be opening two exhibits for which Squalodon whitmorei would be a perfect match. WSC is a Smithsonian Affiliate, so I put in a request through the Affiliates Program to get 3D scans of the skeleton. With their help we arranged to have Bernard Means, a Valley of the Mastodons alum and director of the Virtual Curation Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University visit the Smithsonian and begin scanning the skeleton. While there are still more bones to scan, the cranium has been completed and printed (in six parts) on our Lulzbot printers. Last night I finished painting the printed cranium, which is what I'm holding in the image at the top.We'll be using the printed skull in various education programs at WSC until it goes on exhibit next year.

After successfully defending my undergraduate thesis, I enrolled in graduate school at LSU, and continued my work on squalodonts. This skeleton, along with an additional skull discovered in Virginia in the 1990's, became the main subjects in Chapter 4 of my doctoral dissertation.After completing my doctorate I accepted a position at VMNH, and spent some of my time finishing up projects I had started in graduate school. Finally, in 2005 I formally published "A new species of Squalodon (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Miocene of eastern North America". That paper established the new species Squalodon whitmorei (named in honor of Frank Whitmore), with this specimen as the holotype.As it turns out, in 2019 and 2020 Western Science Center will be opening two exhibits for which Squalodon whitmorei would be a perfect match. WSC is a Smithsonian Affiliate, so I put in a request through the Affiliates Program to get 3D scans of the skeleton. With their help we arranged to have Bernard Means, a Valley of the Mastodons alum and director of the Virtual Curation Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University visit the Smithsonian and begin scanning the skeleton. While there are still more bones to scan, the cranium has been completed and printed (in six parts) on our Lulzbot printers. Last night I finished painting the printed cranium, which is what I'm holding in the image at the top.We'll be using the printed skull in various education programs at WSC until it goes on exhibit next year.

Fossil Friday - ground sloths & therizinosaurs

In many ways, dinosaurs and mammals are very different types of animal. And yet, there are some amazing cases of convergent evolution among them. One of the most bizarre is that of giant ground sloths and therizinosaurs. Like the little slow-moving, tree-dwelling sloths of today, giant ground sloths, like this Paramylodon mounted at Western Science Center, were herbivorous. As a group, sloths are related to armadillos and anteaters. Therizinosaurs, like this Nothronychus mounted at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, are part of Maniraptora, a group of theropod dinosaurs that also includes predators like Velociraptor and our living dinosaurs, the birds. However, therizinosaurs evolved into big feathery herbivores.

In many ways, dinosaurs and mammals are very different types of animal. And yet, there are some amazing cases of convergent evolution among them. One of the most bizarre is that of giant ground sloths and therizinosaurs. Like the little slow-moving, tree-dwelling sloths of today, giant ground sloths, like this Paramylodon mounted at Western Science Center, were herbivorous. As a group, sloths are related to armadillos and anteaters. Therizinosaurs, like this Nothronychus mounted at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, are part of Maniraptora, a group of theropod dinosaurs that also includes predators like Velociraptor and our living dinosaurs, the birds. However, therizinosaurs evolved into big feathery herbivores.  Despite their very different evolutionary origins, giant grounds sloths and therizinosaurs share some remarkable similarities: long arms ending in huge claws, wide bodies to accommodate a long digestive tract for processing plant matter, short robust legs, and short tails. Both groups evolved into large-bodied bipedal plant-eaters. Nothronychus was named in 2001 by my colleagues Jim Kirkland (Utah Geological Survey) and Doug Wolfe (Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences) - the name means "sloth claw".Another similarity is that both giant ground sloths and therizinosaurs represent migrations into North America from other places. Giant ground sloths evolved in South America and reached North America around nine million years ago. Until the discovery of 90-million-year-old Nothronychus in New Mexico, therizinosaurs were known only from fossils found in Asia. Nothronychus is closely related to the large Asian therizinosaurs and probably represents a migration event into western North America.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Despite their very different evolutionary origins, giant grounds sloths and therizinosaurs share some remarkable similarities: long arms ending in huge claws, wide bodies to accommodate a long digestive tract for processing plant matter, short robust legs, and short tails. Both groups evolved into large-bodied bipedal plant-eaters. Nothronychus was named in 2001 by my colleagues Jim Kirkland (Utah Geological Survey) and Doug Wolfe (Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences) - the name means "sloth claw".Another similarity is that both giant ground sloths and therizinosaurs represent migrations into North America from other places. Giant ground sloths evolved in South America and reached North America around nine million years ago. Until the discovery of 90-million-year-old Nothronychus in New Mexico, therizinosaurs were known only from fossils found in Asia. Nothronychus is closely related to the large Asian therizinosaurs and probably represents a migration event into western North America.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald