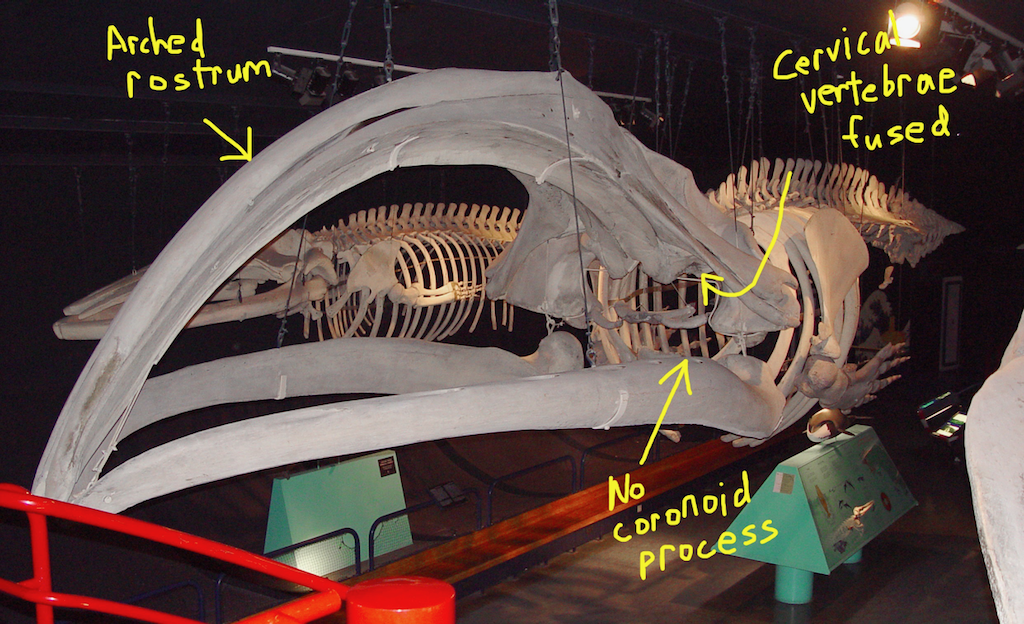

Last summer we took delivery of Mystic, a Pliocene baleen whale from Santa Cruz County. It will take us years to fully prepare Mystic, but we have started working on it, and we've made some interesting progress.Back in July, I tentatively identified Mystic as a possible member of the right whale family (the Balaenidae), based on its large size, the arched rostrum (upper jaw), and the lack of a coronoid process on the mandible. Below is a skeleton of the modern bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus, showing those features (photo from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, taken by Nick Fraser):

Last summer we took delivery of Mystic, a Pliocene baleen whale from Santa Cruz County. It will take us years to fully prepare Mystic, but we have started working on it, and we've made some interesting progress.Back in July, I tentatively identified Mystic as a possible member of the right whale family (the Balaenidae), based on its large size, the arched rostrum (upper jaw), and the lack of a coronoid process on the mandible. Below is a skeleton of the modern bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus, showing those features (photo from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, taken by Nick Fraser): The fused cervical vertebrae are not visible in the photo above, but an interesting feature of balaenids is that all seven neck vertebrae are fused in both modern genera at a very young age, and the first six are fused in the only fossil genus with a known vertebral column, Balaenula (example below from the Pliocene of Virginia, at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences):

The fused cervical vertebrae are not visible in the photo above, but an interesting feature of balaenids is that all seven neck vertebrae are fused in both modern genera at a very young age, and the first six are fused in the only fossil genus with a known vertebral column, Balaenula (example below from the Pliocene of Virginia, at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences): In recent weeks, we've been working around the back of Mystic's head, and noticed a series of vertebrae (after the photo is a version with the vertebrae circled):

In recent weeks, we've been working around the back of Mystic's head, and noticed a series of vertebrae (after the photo is a version with the vertebrae circled):

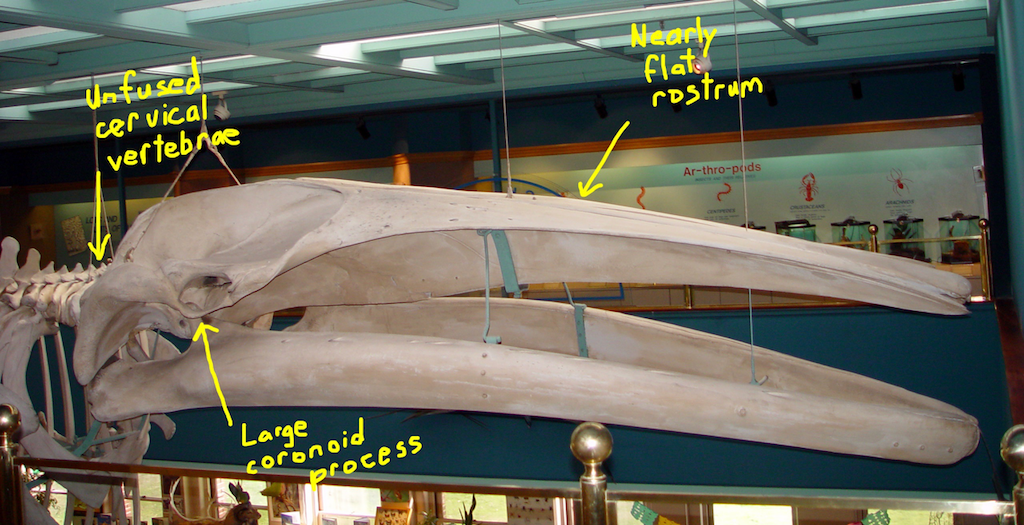

Most of these vertebrae are articulated, or nearly so. But the ones in yellow are of particular interest. They have transverse processes with no obvious rib articulations, and the vertebral centra are very short. That makes them look like cervical vertebrae, but they aren't fused. As mentioned above, all known members of the right whale family have fused cervicals. So, do we have other options?Balaenopterids (blue whales, humpback whales, and their relatives) have unfused cervical vertebrae, but their rostra are only slightly arched, and, more significantly, they all have very large, prominent coronoid processes (fin whale Balaenoptera physalis below from the Los Angeles County Museum):

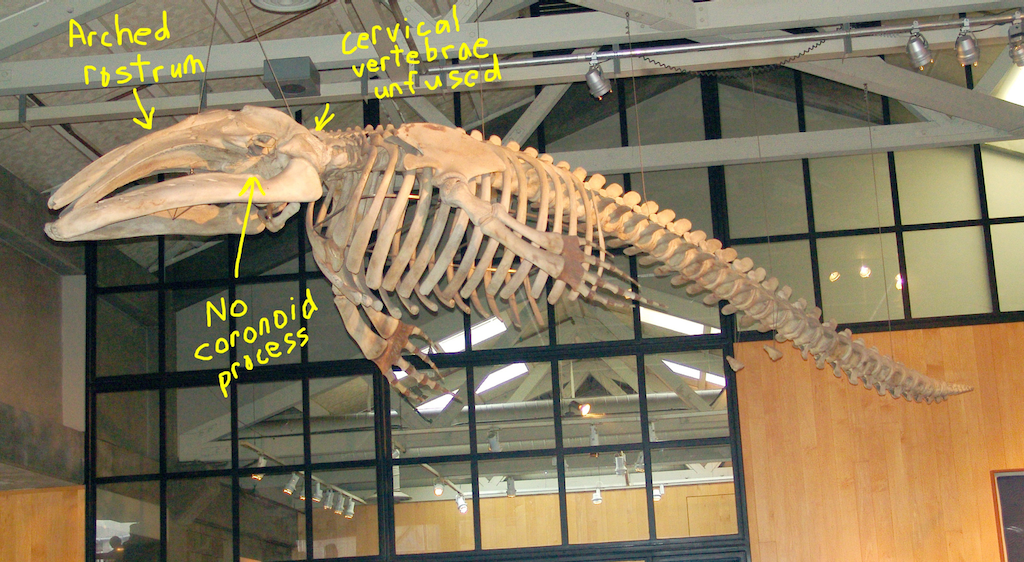

Most of these vertebrae are articulated, or nearly so. But the ones in yellow are of particular interest. They have transverse processes with no obvious rib articulations, and the vertebral centra are very short. That makes them look like cervical vertebrae, but they aren't fused. As mentioned above, all known members of the right whale family have fused cervicals. So, do we have other options?Balaenopterids (blue whales, humpback whales, and their relatives) have unfused cervical vertebrae, but their rostra are only slightly arched, and, more significantly, they all have very large, prominent coronoid processes (fin whale Balaenoptera physalis below from the Los Angeles County Museum): However, there are also gray whales (example below from the Monterey Bay Aquarium):

However, there are also gray whales (example below from the Monterey Bay Aquarium): Like balaenopterids (and, in fact, all mysticetes except the right whales), gray whales have unfused cervical vertebrae. But, like right whales, they have an arched rostrum (although not as arched as in the right whales) and lack a coronoid process.If we're interpreting Mystic's features correctly, I now think there's a good chance it could be a gray whale instead of a right whale. There have been other fossil gray whales found in Pliocene deposits from California, especially from the San Diego Formation, but they don't seem to be terribly common, so this would still be a great find.Stay tuned for more over the next five years or so!

Like balaenopterids (and, in fact, all mysticetes except the right whales), gray whales have unfused cervical vertebrae. But, like right whales, they have an arched rostrum (although not as arched as in the right whales) and lack a coronoid process.If we're interpreting Mystic's features correctly, I now think there's a good chance it could be a gray whale instead of a right whale. There have been other fossil gray whales found in Pliocene deposits from California, especially from the San Diego Formation, but they don't seem to be terribly common, so this would still be a great find.Stay tuned for more over the next five years or so!

Fossil Friday - Squalodon whitmorei

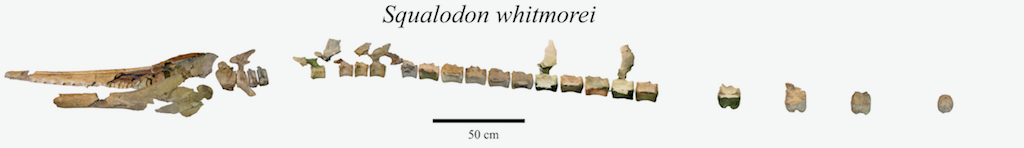

Usually we use our Fossil Friday posts to talk about specimens that are housed in the WSC collections. But today I'm going to talk about our newest 3D print, the skull of the primitive toothed whale Squalodon whitmorei.Squalodonts are a family of toothed whales that lived in the Oligocene and the first half of the Miocene. At one time it was thought they might be close to the transition between Eocene archaeocete whales and modern dolphins and other toothed cetaceans. It turns out they were their own specialized branch of toothed whales, members of a once widespread group called the platanistoids that has since been mostly supplanted by the delphinoids. They have a somewhat primitive look largely because of their extremely heterodont teeth, including serrated, triangular back teeth (hence the name Squalodon, which literally means "shark tooth"). They were among the last groups of cetaceans (maybe THE last group) to retain these triangular, double-rooted back teeth. They are best known from Europe and eastern North America, but examples have been found all over the world.This specimen holds a special place for me, because it was the first fossil vertebrate I ever had the chance to work on. In 1989 I traveled to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to talk about possible research topics for my senior thesis at Carleton College. I met paleontologists Clayton Ray, Frank Whitmore, and Dave Bohaska while I was there, and after a day of looking at fossils they suggested that if I wanted to I could come back next summer and work on squalodont whales for my thesis (a group I had never heard of before).The next summer, after securing free housing from a Carleton alumnus, Frank turned over to me several boxes of bone fragments that had been collected by a boy scout troop in Virginia in the 1970s. I spent the next 2 months learning techniques for cleaning and repairing fossils, while Frank tutored my on cetacean anatomy. By the end of the summer I had put together one of the most complete known skeletons of Squalodon, the largest example of the genus ever found:

Usually we use our Fossil Friday posts to talk about specimens that are housed in the WSC collections. But today I'm going to talk about our newest 3D print, the skull of the primitive toothed whale Squalodon whitmorei.Squalodonts are a family of toothed whales that lived in the Oligocene and the first half of the Miocene. At one time it was thought they might be close to the transition between Eocene archaeocete whales and modern dolphins and other toothed cetaceans. It turns out they were their own specialized branch of toothed whales, members of a once widespread group called the platanistoids that has since been mostly supplanted by the delphinoids. They have a somewhat primitive look largely because of their extremely heterodont teeth, including serrated, triangular back teeth (hence the name Squalodon, which literally means "shark tooth"). They were among the last groups of cetaceans (maybe THE last group) to retain these triangular, double-rooted back teeth. They are best known from Europe and eastern North America, but examples have been found all over the world.This specimen holds a special place for me, because it was the first fossil vertebrate I ever had the chance to work on. In 1989 I traveled to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to talk about possible research topics for my senior thesis at Carleton College. I met paleontologists Clayton Ray, Frank Whitmore, and Dave Bohaska while I was there, and after a day of looking at fossils they suggested that if I wanted to I could come back next summer and work on squalodont whales for my thesis (a group I had never heard of before).The next summer, after securing free housing from a Carleton alumnus, Frank turned over to me several boxes of bone fragments that had been collected by a boy scout troop in Virginia in the 1970s. I spent the next 2 months learning techniques for cleaning and repairing fossils, while Frank tutored my on cetacean anatomy. By the end of the summer I had put together one of the most complete known skeletons of Squalodon, the largest example of the genus ever found:

After successfully defending my undergraduate thesis, I enrolled in graduate school at LSU, and continued my work on squalodonts. This skeleton, along with an additional skull discovered in Virginia in the 1990's, became the main subjects in Chapter 4 of my doctoral dissertation.After completing my doctorate I accepted a position at VMNH, and spent some of my time finishing up projects I had started in graduate school. Finally, in 2005 I formally published "A new species of Squalodon (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Miocene of eastern North America". That paper established the new species Squalodon whitmorei (named in honor of Frank Whitmore), with this specimen as the holotype.As it turns out, in 2019 and 2020 Western Science Center will be opening two exhibits for which Squalodon whitmorei would be a perfect match. WSC is a Smithsonian Affiliate, so I put in a request through the Affiliates Program to get 3D scans of the skeleton. With their help we arranged to have Bernard Means, a Valley of the Mastodons alum and director of the Virtual Curation Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University visit the Smithsonian and begin scanning the skeleton. While there are still more bones to scan, the cranium has been completed and printed (in six parts) on our Lulzbot printers. Last night I finished painting the printed cranium, which is what I'm holding in the image at the top.We'll be using the printed skull in various education programs at WSC until it goes on exhibit next year.

After successfully defending my undergraduate thesis, I enrolled in graduate school at LSU, and continued my work on squalodonts. This skeleton, along with an additional skull discovered in Virginia in the 1990's, became the main subjects in Chapter 4 of my doctoral dissertation.After completing my doctorate I accepted a position at VMNH, and spent some of my time finishing up projects I had started in graduate school. Finally, in 2005 I formally published "A new species of Squalodon (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Miocene of eastern North America". That paper established the new species Squalodon whitmorei (named in honor of Frank Whitmore), with this specimen as the holotype.As it turns out, in 2019 and 2020 Western Science Center will be opening two exhibits for which Squalodon whitmorei would be a perfect match. WSC is a Smithsonian Affiliate, so I put in a request through the Affiliates Program to get 3D scans of the skeleton. With their help we arranged to have Bernard Means, a Valley of the Mastodons alum and director of the Virtual Curation Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University visit the Smithsonian and begin scanning the skeleton. While there are still more bones to scan, the cranium has been completed and printed (in six parts) on our Lulzbot printers. Last night I finished painting the printed cranium, which is what I'm holding in the image at the top.We'll be using the printed skull in various education programs at WSC until it goes on exhibit next year.

Fossil Friday - a whale for WSC

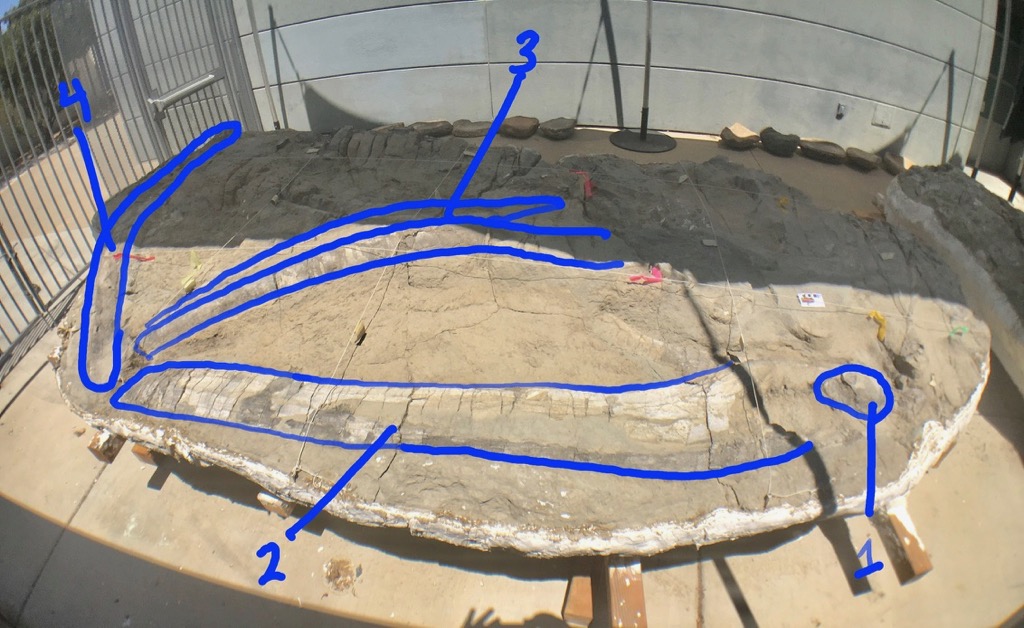

A few weeks ago, Western Science Center took delivery of the first fossil whale in our collection.This specimen was collected by PaleoSolutions during a construction project in Santa Cruz County. There are five separate field jackets, including one monster that's five meters long! That's the jacket shown above (notice the tiny scale bar on the right).This whale was found in Pliocene deposits, between 2 and 5 million years old. California has rich deposits of Pliocene whales, so when we've finished preparing this specimen (likely several years from now) there should be a lot with which to compare it. But even now, we can say a few things about it. First, this is a filter-feeding baleen whale from the suborder Mysticeti (hence the publicly-nominated nickname, Mystic). The only toothed whales (odontocetes) that get this large are sperm whales, and none of the visible cranial bones resembles the highly specialized elements in sperm whales. Below is a marked-up image with a few of the visible bones outlined (apologies for the lighting):

A few weeks ago, Western Science Center took delivery of the first fossil whale in our collection.This specimen was collected by PaleoSolutions during a construction project in Santa Cruz County. There are five separate field jackets, including one monster that's five meters long! That's the jacket shown above (notice the tiny scale bar on the right).This whale was found in Pliocene deposits, between 2 and 5 million years old. California has rich deposits of Pliocene whales, so when we've finished preparing this specimen (likely several years from now) there should be a lot with which to compare it. But even now, we can say a few things about it. First, this is a filter-feeding baleen whale from the suborder Mysticeti (hence the publicly-nominated nickname, Mystic). The only toothed whales (odontocetes) that get this large are sperm whales, and none of the visible cranial bones resembles the highly specialized elements in sperm whales. Below is a marked-up image with a few of the visible bones outlined (apologies for the lighting): The bone labeled "1" is a vertebra, probably a thoracic or lumbar vertebra. This specimen includes numerous vertebrae, and all of them seem to have fused vertebral epiphyses, indicating that the whale is an adult.Number 2 is the left dentary; the left side of the lower jaw. It's not clear yet how much of the dentary is preserved, so it may be a bit longer than what is visible here. An interesting and important feature is the apparent absence of a coronoid process. The largest living group of baleen whales, the Balaenopteridae (including blue, fin, and humpback whales, among others) all have a large, prominent coronoid process. That means this specimen is more likely member of the right whale family (Balaenidae) or the grey whale family (Eschrichtiidae). (The weird pygmy right whale also lacks a coronoid process, and may not even be a right whale, but Mystic is not a pygmy right whale.)Number 3 I think are the premaxillae, which in whales extend from the tip of the upper jaw all the way to near the blowhole. These are strongly arched, which is consistent with both right whales and grey whales, but to me these look a bit more like a right whale.Number 4 I'm not sure about. I briefly thought is might be the broken continuation of the dentary, but I don't think that's right. The shape is wrong, and if you add that to bone 2 the dentary would be up in the blue whale-size range; Mystic isn't that big! I now think this might be the displaced and rotated maxilla. It should be running parallel to the premaxilla, so if it really is the maxilla it is way out of position, but this isn't unheard of. That shape is also consistent with a right whale maxilla.So, if this is a right whale (by no means a certainty), which right whale is it? There are actually only a handful of fossil right whale genera known. Of the four Pliocene genera, tiny Balaenella is only known from northern Europe, and is smaller than Mystic. Balaena includes the living bowhead whale as well as some extinct species. Eubalaena includes the three living right whale species, as well as several extinct ones. Most species of Balaena and Eubalaena are giants, quite a bit larger that Mystic (remember Mystic is an adult). I'm not ready to rule them out, but they seem unlikely. The fourth known Pliocene balaenid is Balaenula, a poorly understood genus that is known from all over the northern hemisphere, including California. Balaenula is a fairly small whale, and I think Mystic is likely a bit larger. But, if Mystic belongs to any right whale genus that has already been described, I think Balaenula is the best candidate.Mystic is on display in an outdoor preparation area at Western Science Center, so that the public can follow progress on its preparation in the years to come.

The bone labeled "1" is a vertebra, probably a thoracic or lumbar vertebra. This specimen includes numerous vertebrae, and all of them seem to have fused vertebral epiphyses, indicating that the whale is an adult.Number 2 is the left dentary; the left side of the lower jaw. It's not clear yet how much of the dentary is preserved, so it may be a bit longer than what is visible here. An interesting and important feature is the apparent absence of a coronoid process. The largest living group of baleen whales, the Balaenopteridae (including blue, fin, and humpback whales, among others) all have a large, prominent coronoid process. That means this specimen is more likely member of the right whale family (Balaenidae) or the grey whale family (Eschrichtiidae). (The weird pygmy right whale also lacks a coronoid process, and may not even be a right whale, but Mystic is not a pygmy right whale.)Number 3 I think are the premaxillae, which in whales extend from the tip of the upper jaw all the way to near the blowhole. These are strongly arched, which is consistent with both right whales and grey whales, but to me these look a bit more like a right whale.Number 4 I'm not sure about. I briefly thought is might be the broken continuation of the dentary, but I don't think that's right. The shape is wrong, and if you add that to bone 2 the dentary would be up in the blue whale-size range; Mystic isn't that big! I now think this might be the displaced and rotated maxilla. It should be running parallel to the premaxilla, so if it really is the maxilla it is way out of position, but this isn't unheard of. That shape is also consistent with a right whale maxilla.So, if this is a right whale (by no means a certainty), which right whale is it? There are actually only a handful of fossil right whale genera known. Of the four Pliocene genera, tiny Balaenella is only known from northern Europe, and is smaller than Mystic. Balaena includes the living bowhead whale as well as some extinct species. Eubalaena includes the three living right whale species, as well as several extinct ones. Most species of Balaena and Eubalaena are giants, quite a bit larger that Mystic (remember Mystic is an adult). I'm not ready to rule them out, but they seem unlikely. The fourth known Pliocene balaenid is Balaenula, a poorly understood genus that is known from all over the northern hemisphere, including California. Balaenula is a fairly small whale, and I think Mystic is likely a bit larger. But, if Mystic belongs to any right whale genus that has already been described, I think Balaenula is the best candidate.Mystic is on display in an outdoor preparation area at Western Science Center, so that the public can follow progress on its preparation in the years to come.