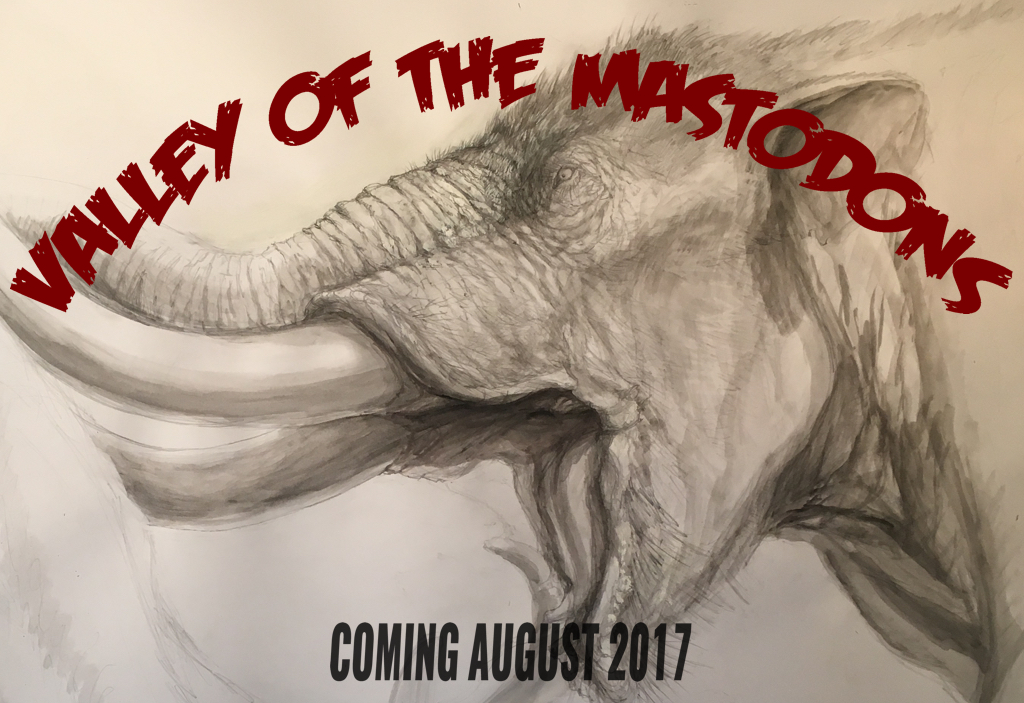

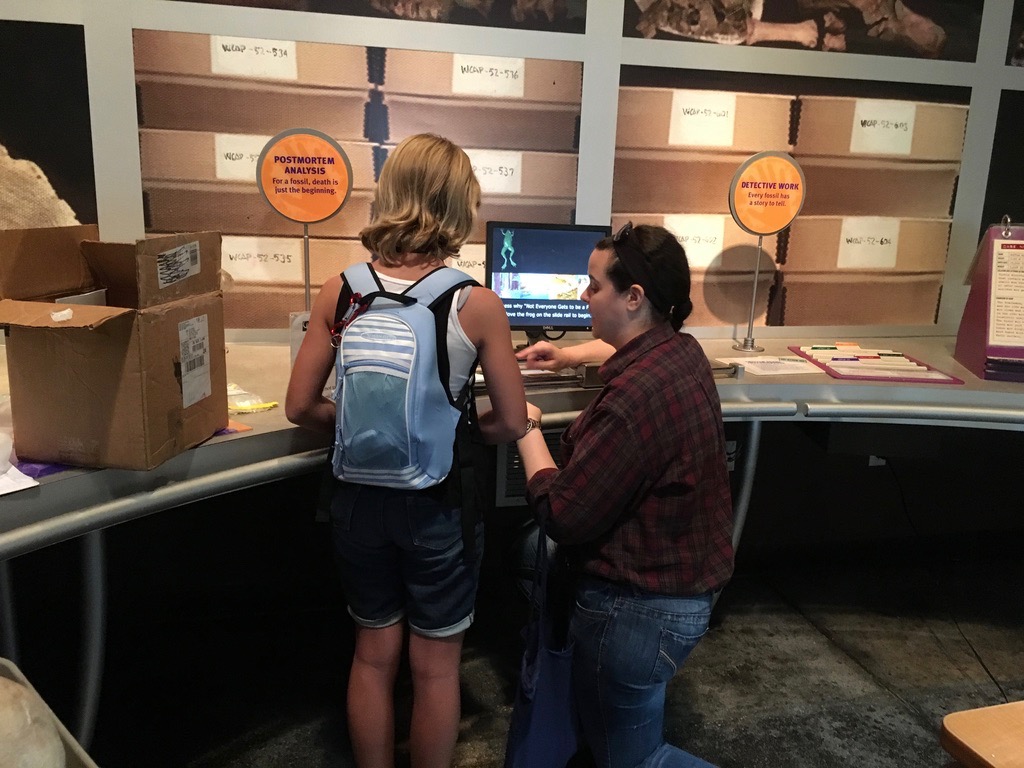

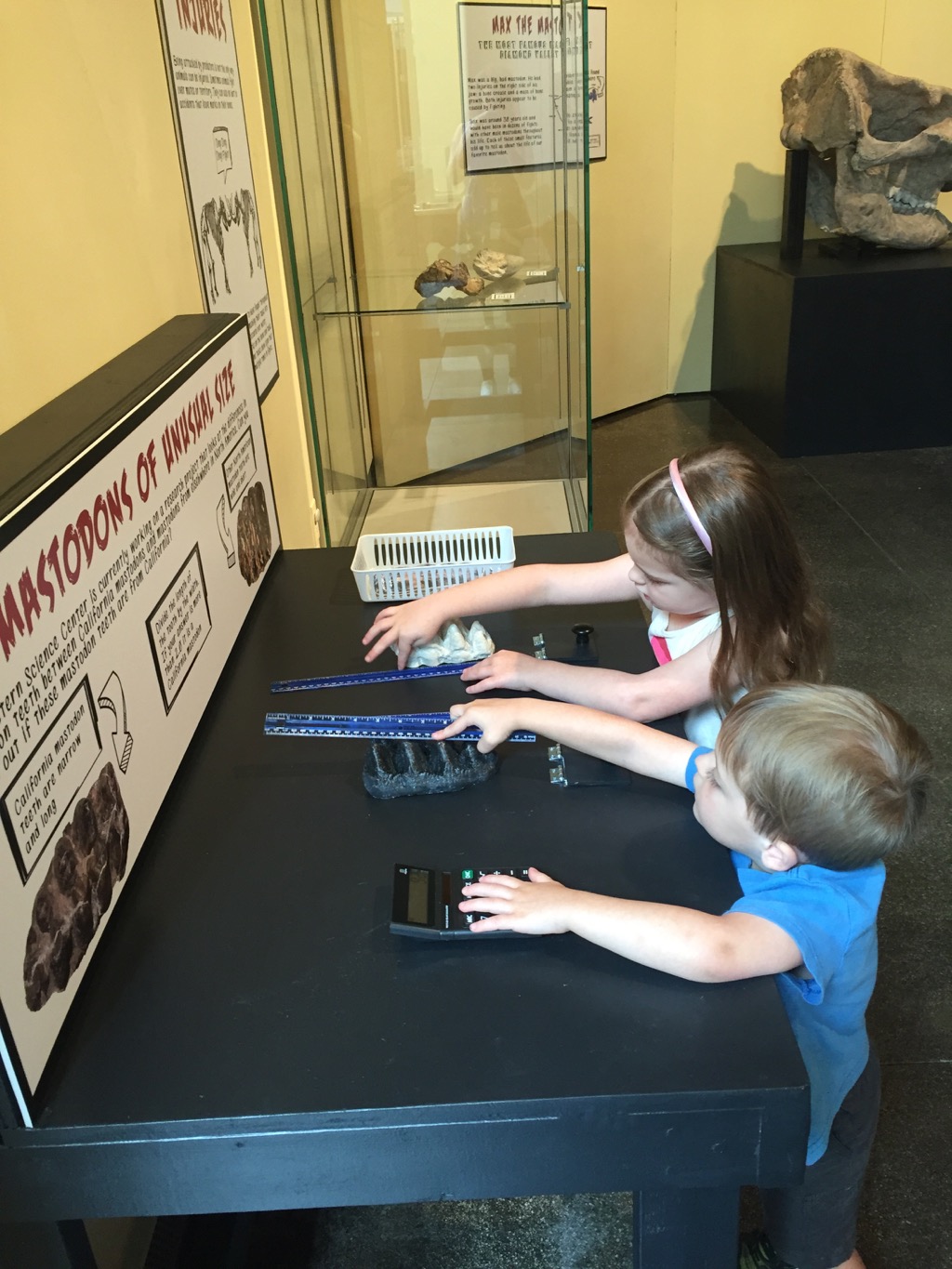

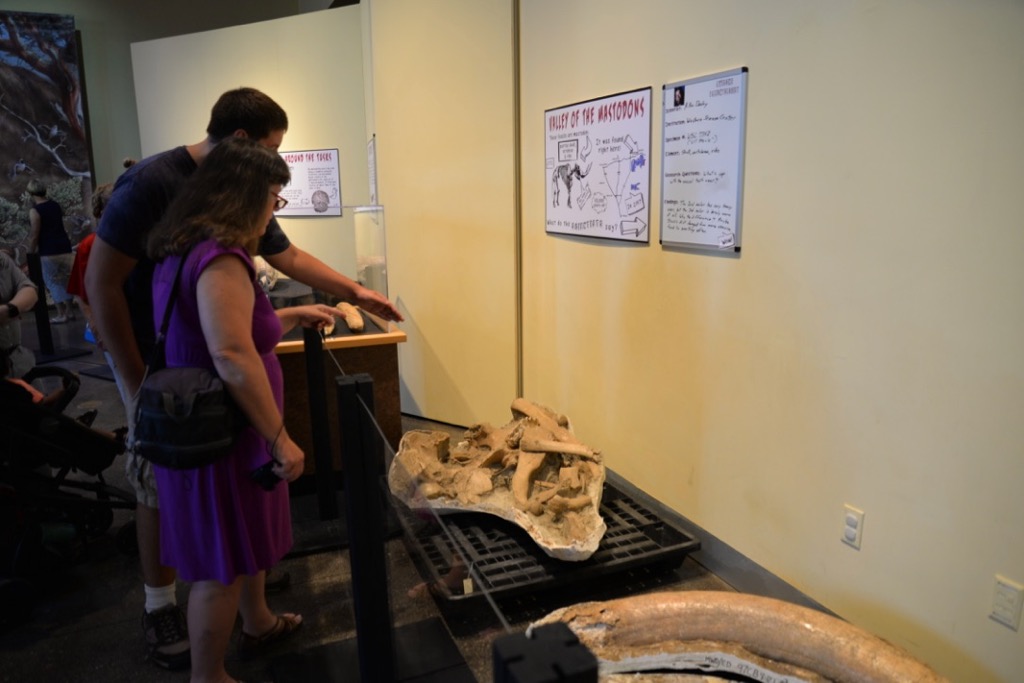

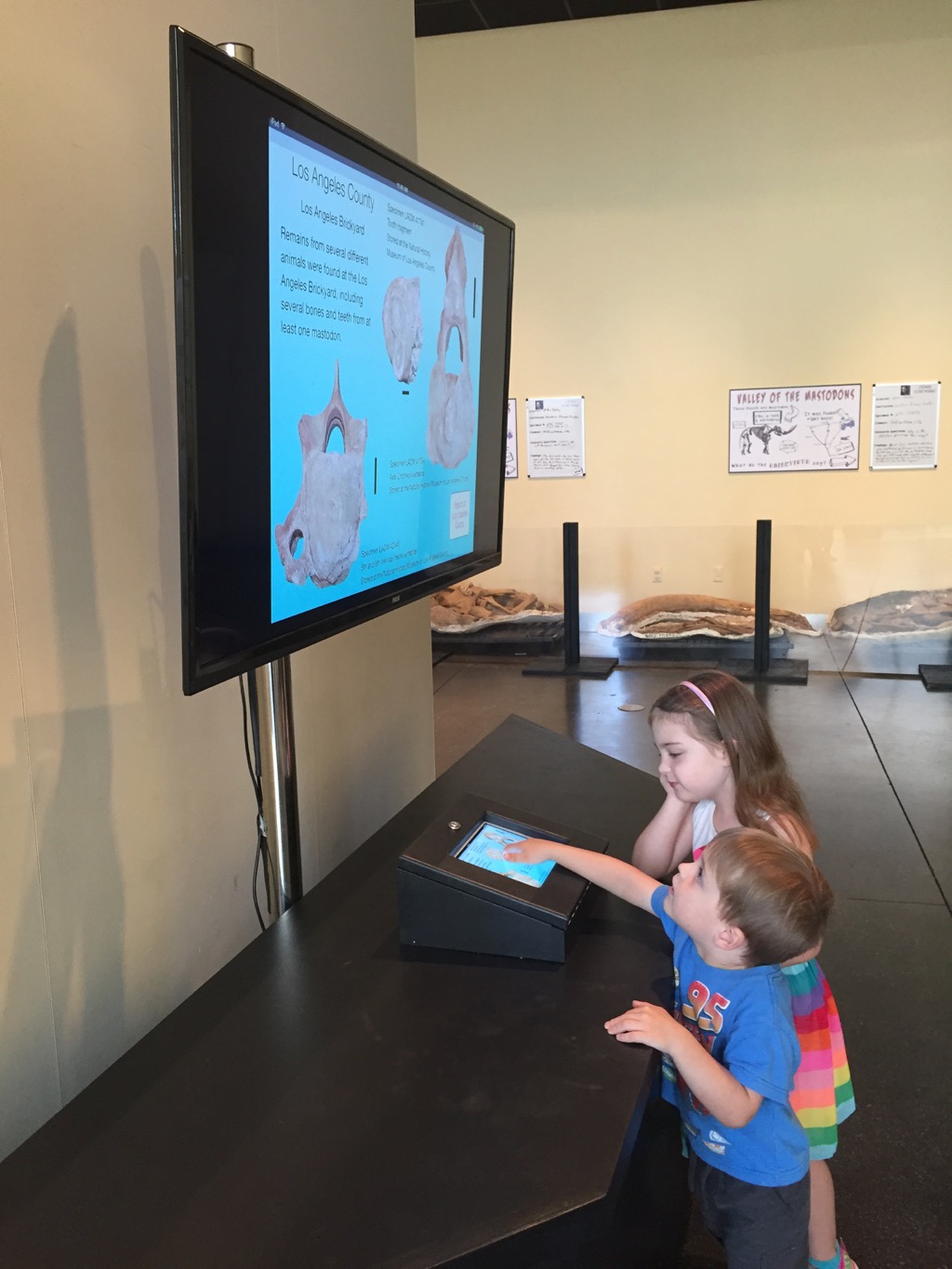

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

SE GSA meeting Day 2

I'm on my way back home from the SE GSA conference, and I finally have a chance to write about the second day of the meeting. Things got very busy at the WSC booth (we sold most of our inventory of casts!), and as a result I missed the entire morning session of talks except for single poster.That poster was by Nickacia Young and Rowan Lockwood on the effects of cementation on the preservation of fossil shells in Late Miocene deposits on the Virginia Coastal Plain. These deposits, called the Eastover Formation, are extremely rich in fossil shells. They are usually unlithified, meaning that the sediments are soft and can be dug out with a pick and shovel, such as in the image above. But in a few places the Eastover is lithified, meaning that it has fused into solid rock, as with the orange blocks in the image below:

I'm on my way back home from the SE GSA conference, and I finally have a chance to write about the second day of the meeting. Things got very busy at the WSC booth (we sold most of our inventory of casts!), and as a result I missed the entire morning session of talks except for single poster.That poster was by Nickacia Young and Rowan Lockwood on the effects of cementation on the preservation of fossil shells in Late Miocene deposits on the Virginia Coastal Plain. These deposits, called the Eastover Formation, are extremely rich in fossil shells. They are usually unlithified, meaning that the sediments are soft and can be dug out with a pick and shovel, such as in the image above. But in a few places the Eastover is lithified, meaning that it has fused into solid rock, as with the orange blocks in the image below: According to Young and Lockwood the number of species of shells (the diversity) in the lithified Eastover is much lower than in unlithified samples. This could have implications in estimating biodiversity in other deposits in which the entire deposit is lithified; if it behaves like the Eastover we may only be seeing a small subset of the species that were originally present.In the afternoon I pick up a couple of talks in a session on faults and shear zones in the Appalachians. John Hickman discussed deeply buried fault zones beneath Kentucky, and suggested that they form part of a Precambrian rift system associated with the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Late Proterozoic Eon.The next talk was presented by Chuck Bailey, on which I was one of four coauthors. This was on the presence of Mesozoic faults in the Hylas Fault Zone at the edge of the Virginia Coastal Plain and their effect on younger Cenozoic sediments. I was involved in this talk because one of the study sites was the Carmel Church Quarry, a marine fossil site that I have been excavating for more than 20 years. During and excavation I led at Carmel Church in 2014 we discovered a boulder field buried in the Miocene sediments along with whales and other marine fossils:

According to Young and Lockwood the number of species of shells (the diversity) in the lithified Eastover is much lower than in unlithified samples. This could have implications in estimating biodiversity in other deposits in which the entire deposit is lithified; if it behaves like the Eastover we may only be seeing a small subset of the species that were originally present.In the afternoon I pick up a couple of talks in a session on faults and shear zones in the Appalachians. John Hickman discussed deeply buried fault zones beneath Kentucky, and suggested that they form part of a Precambrian rift system associated with the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Late Proterozoic Eon.The next talk was presented by Chuck Bailey, on which I was one of four coauthors. This was on the presence of Mesozoic faults in the Hylas Fault Zone at the edge of the Virginia Coastal Plain and their effect on younger Cenozoic sediments. I was involved in this talk because one of the study sites was the Carmel Church Quarry, a marine fossil site that I have been excavating for more than 20 years. During and excavation I led at Carmel Church in 2014 we discovered a boulder field buried in the Miocene sediments along with whales and other marine fossils: I suspected that structural activity might be responsible for the presence of these boulders, and since Chuck was working on faults in this region I asked him to take a look at the boulder field. Based on work by Chuck and his students it appears that the boulder field was most likely formed by the reactivation of a Triassic fault in the Miocene.As soon as Chuck's talk was finished I raced to another lecture hall to catch the end of a session on teaching evolution in the southeast, organized by Patricia Kelley and Christy Visaggi. This was actually an all-day session with 16 talks, and while the booth kept me away from the morning session Brett was able to attend. I had to attend the afternoon session, though, because Brett and I were jointly presenting a talk on teaching activities for getting students used to making hypotheses based on limited data. This included a description of the cast-based teaching kits that Brett and I have been developing based on specimens housed at the Western Science Center, as well as the adaptation of online lessons for courses in historical sciences.The last talks at SE GSA were Friday afternoon. There were also several post-meeting field trips on Saturday, but with long drives ahead of us Brett and I had to start heading back to Virginia and California, respectively. This was a fun and productive meeting, and I have to say that, having attended conferences in dozens of cities, Chattanooga was one of the nicest conference cities I've ever seen.

I suspected that structural activity might be responsible for the presence of these boulders, and since Chuck was working on faults in this region I asked him to take a look at the boulder field. Based on work by Chuck and his students it appears that the boulder field was most likely formed by the reactivation of a Triassic fault in the Miocene.As soon as Chuck's talk was finished I raced to another lecture hall to catch the end of a session on teaching evolution in the southeast, organized by Patricia Kelley and Christy Visaggi. This was actually an all-day session with 16 talks, and while the booth kept me away from the morning session Brett was able to attend. I had to attend the afternoon session, though, because Brett and I were jointly presenting a talk on teaching activities for getting students used to making hypotheses based on limited data. This included a description of the cast-based teaching kits that Brett and I have been developing based on specimens housed at the Western Science Center, as well as the adaptation of online lessons for courses in historical sciences.The last talks at SE GSA were Friday afternoon. There were also several post-meeting field trips on Saturday, but with long drives ahead of us Brett and I had to start heading back to Virginia and California, respectively. This was a fun and productive meeting, and I have to say that, having attended conferences in dozens of cities, Chattanooga was one of the nicest conference cities I've ever seen.

Geological Society of America Southeastern section meeting

I'm currently on a trip back east, primarily to give presentations at two different professional conferences. After meeting up with my wife, Brett, we drove to Chicago to attend the National Science Teachers' Association meeting. While there we conducted a workshop on producing virtual field trip e-books for iPads, and gave a presentation on WSC's paleontology teaching kits; Brett gave additional presentations on using mammal skulls to teach about trophic levels and on webquests. We then left Chicago and headed south to Chattanooga for the Geological Society of America Southeastern Section meeting (SEGSA).In addition to our presentations at SEGSA, Brett and I are running an exhibitor's booth (above) to give the participants information about the Western Science Center and to sell teaching kits and cast replicas of specimens to raise funds for the museum.Running our booth cuts into my time for attending presentations, but I did make it to several talks and quite a few posters (generally my favorite part of the meeting). The morning posters included a session on Geoscience Education, including one by Andy Heckert of Appalachian State on a student exercise to describe their hometown geology. In the same session Zoe Zeszut and coauthors presented on Ohio University's Digital Atlas of Ordovician Life, an online guide to the Ordovician fossils of Ohio and the surrounding regions, such as these highly fossiliferous beds just across the state line in Kentucky:

I'm currently on a trip back east, primarily to give presentations at two different professional conferences. After meeting up with my wife, Brett, we drove to Chicago to attend the National Science Teachers' Association meeting. While there we conducted a workshop on producing virtual field trip e-books for iPads, and gave a presentation on WSC's paleontology teaching kits; Brett gave additional presentations on using mammal skulls to teach about trophic levels and on webquests. We then left Chicago and headed south to Chattanooga for the Geological Society of America Southeastern Section meeting (SEGSA).In addition to our presentations at SEGSA, Brett and I are running an exhibitor's booth (above) to give the participants information about the Western Science Center and to sell teaching kits and cast replicas of specimens to raise funds for the museum.Running our booth cuts into my time for attending presentations, but I did make it to several talks and quite a few posters (generally my favorite part of the meeting). The morning posters included a session on Geoscience Education, including one by Andy Heckert of Appalachian State on a student exercise to describe their hometown geology. In the same session Zoe Zeszut and coauthors presented on Ohio University's Digital Atlas of Ordovician Life, an online guide to the Ordovician fossils of Ohio and the surrounding regions, such as these highly fossiliferous beds just across the state line in Kentucky: The afternoon session included most of the paleontology posters, including the first of my three presentations. Shortly before I left the Virginia Museum of Natural History (VMNH) I received a grant from the National Geographic Society to run a salvage operation at the Solite Quarry, a Triassic Period deposit on the Virginia/North Carolina state line that includes spectacular fossils of reptiles, fish, plants, and insects. My poster included five coauthors from VMNH, Appalachian State, and the National Museum of Scotland and was basically a progress report on the state of the salvage operation. I got the salvage operation started as one of my last activities at VMNH (below), and they continued the operation after my departure to WSC. The salvage work has resulted in the collection of a large number of new fossils, some of which were only known previously by a handful of specimens.

The afternoon session included most of the paleontology posters, including the first of my three presentations. Shortly before I left the Virginia Museum of Natural History (VMNH) I received a grant from the National Geographic Society to run a salvage operation at the Solite Quarry, a Triassic Period deposit on the Virginia/North Carolina state line that includes spectacular fossils of reptiles, fish, plants, and insects. My poster included five coauthors from VMNH, Appalachian State, and the National Museum of Scotland and was basically a progress report on the state of the salvage operation. I got the salvage operation started as one of my last activities at VMNH (below), and they continued the operation after my departure to WSC. The salvage work has resulted in the collection of a large number of new fossils, some of which were only known previously by a handful of specimens. Just to prove that I do, in fact, do field work!In some of the other paleontology section posters, Jennifer Bradham, Larisa DeSantis, and Malu Jorge used stable isotope data nd dental microwear to compare the diets of Florida specimens of the Pliocene peccaries Mylohyus (below, at top, from the Texas Memorial Museum) and Platygonus (below, at bottom, from the American Museum of Natural History):

Just to prove that I do, in fact, do field work!In some of the other paleontology section posters, Jennifer Bradham, Larisa DeSantis, and Malu Jorge used stable isotope data nd dental microwear to compare the diets of Florida specimens of the Pliocene peccaries Mylohyus (below, at top, from the Texas Memorial Museum) and Platygonus (below, at bottom, from the American Museum of Natural History):

Three different posters examine various aspects of drill holes on mollusk shells, formed when predators drill a hole through the shell to get at the animal inside (as in the shell shown below):

Three different posters examine various aspects of drill holes on mollusk shells, formed when predators drill a hole through the shell to get at the animal inside (as in the shell shown below): Kathryn Estes-Smargiassi and three coauthors looked at these drill holes specifically on scaphopods, or tusk shells. Patricia Kelley and six coauthors examined the paleoecological patterns of drill predation on Pleistocene mollusks from Florida. And, while these drill holes are usually formed by predatory snails, Deborah Freile and three coauthors looked at examples of shells that had been drilled by octopi.Late in the afternoon I left the posters to catch the last three talks in the paleoichnology (trace fossil) session. Kelli Straka and five coauthors reported on coprolites (fossil poo) containing teeth, fish scales, and bone fragments from Triassic deposits in Arizona, while David Schwimmer presented on Cretaceous coprolites from the southeast, including examples from fish, sharks, and crocodilians, including a shark coprolite that contained almost the entire neck of a baby turtle. In the last talk in the session Tony Martin and three coauthors reported on modern alligator burrows from Georgia barrier islands, large structures that can be up to several meters long.These meeting are also a nice opportunity to keep in contact with old colleagues. I was pleasantly surprised when the WSC booth was visited by Heyo van Iten from Hanover College (below). Heyo was my undergraduate paleontology professor at Carleton College more than 25 years ago.

Kathryn Estes-Smargiassi and three coauthors looked at these drill holes specifically on scaphopods, or tusk shells. Patricia Kelley and six coauthors examined the paleoecological patterns of drill predation on Pleistocene mollusks from Florida. And, while these drill holes are usually formed by predatory snails, Deborah Freile and three coauthors looked at examples of shells that had been drilled by octopi.Late in the afternoon I left the posters to catch the last three talks in the paleoichnology (trace fossil) session. Kelli Straka and five coauthors reported on coprolites (fossil poo) containing teeth, fish scales, and bone fragments from Triassic deposits in Arizona, while David Schwimmer presented on Cretaceous coprolites from the southeast, including examples from fish, sharks, and crocodilians, including a shark coprolite that contained almost the entire neck of a baby turtle. In the last talk in the session Tony Martin and three coauthors reported on modern alligator burrows from Georgia barrier islands, large structures that can be up to several meters long.These meeting are also a nice opportunity to keep in contact with old colleagues. I was pleasantly surprised when the WSC booth was visited by Heyo van Iten from Hanover College (below). Heyo was my undergraduate paleontology professor at Carleton College more than 25 years ago. The meeting continues tomorrow with another full slate of posters and talks.

The meeting continues tomorrow with another full slate of posters and talks.