Pumpkins are an interesting fruit. Curcurbita pepo is one of several domesticated species of the genus Curcurbita, vines that are native to the Americas. Curcurbita is a ecologically diverse genus, with some species needing a continuous water supply while others can live in arid conditions, so it is found natively in a variety of habitats. The fruits, which are technically berries, generally have a thick rind with a softer interior where the seeds are located. In most species the rinds are bitter, but the interior is often more palatable and rich in nutrients. As a result it became one of the first domesticated plants in North America more than 8,000 years ago.With large, nutritious fruits, we can be confident that wild Curcurbita were being eaten by more than just humans. In 2006 Lee Newsom and Matthew Mihlbachler published a detailed report about an American mastodon dung deposit in northern Florida. The vast majority of the dung consisted of small cypress twigs, chopped up and stripped of bark, but there were other plant remains from at least 57 species. Among their samples were 156 Curcurbita seeds, showing that this was a popular item on the mastodon menu. Using the Newsom and Mihlbachler paper as a guide, a few years ago we made a simulated piece of mastodon dung for exhibit at WSC, including numerous pumpkin and squash seeds:

Pumpkins are an interesting fruit. Curcurbita pepo is one of several domesticated species of the genus Curcurbita, vines that are native to the Americas. Curcurbita is a ecologically diverse genus, with some species needing a continuous water supply while others can live in arid conditions, so it is found natively in a variety of habitats. The fruits, which are technically berries, generally have a thick rind with a softer interior where the seeds are located. In most species the rinds are bitter, but the interior is often more palatable and rich in nutrients. As a result it became one of the first domesticated plants in North America more than 8,000 years ago.With large, nutritious fruits, we can be confident that wild Curcurbita were being eaten by more than just humans. In 2006 Lee Newsom and Matthew Mihlbachler published a detailed report about an American mastodon dung deposit in northern Florida. The vast majority of the dung consisted of small cypress twigs, chopped up and stripped of bark, but there were other plant remains from at least 57 species. Among their samples were 156 Curcurbita seeds, showing that this was a popular item on the mastodon menu. Using the Newsom and Mihlbachler paper as a guide, a few years ago we made a simulated piece of mastodon dung for exhibit at WSC, including numerous pumpkin and squash seeds: Newsom and Mihlbachler also noted that, while Curcurbita seeds were relatively common in their sample, rind fragments were almost completely absent. It seems that mastodons may have disliked the bitter rinds just like we do, and broken the gourds open to get at the interior. Captive elephants that are fed pumpkins seem to have discovered the same trick:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CzXH2Eg1hw&w=560&h=315]So far no Pacific mastodon coprolites have been identified, but hopefully one day we'll be able so say as much about their dietary habits.Reference:Lee Newsom and Matthew C. Mihlbachler, 2006. Mastodon (Mammut americanum) diet and foraging patterns based on analysis of dung deposits. Chapter 10 in S. David Webb (ed.), First Floridians and Last Mastodons: The Page-Ladson Site in the Aucilla River, Springer, p. 263-331.

Newsom and Mihlbachler also noted that, while Curcurbita seeds were relatively common in their sample, rind fragments were almost completely absent. It seems that mastodons may have disliked the bitter rinds just like we do, and broken the gourds open to get at the interior. Captive elephants that are fed pumpkins seem to have discovered the same trick:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CzXH2Eg1hw&w=560&h=315]So far no Pacific mastodon coprolites have been identified, but hopefully one day we'll be able so say as much about their dietary habits.Reference:Lee Newsom and Matthew C. Mihlbachler, 2006. Mastodon (Mammut americanum) diet and foraging patterns based on analysis of dung deposits. Chapter 10 in S. David Webb (ed.), First Floridians and Last Mastodons: The Page-Ladson Site in the Aucilla River, Springer, p. 263-331.

Fossil Friday - Mammut pacificus

The big news this week for Western Science Center was the naming of a new species of mastodon, Mammut pacificus.For decades, the consensus on Pleistocene mastodons (which I shared) was that in North America there was only a single, widespread species, Mammut americanum. Four years ago, I stumbled across the fact that California mastodons have different tooth proportions than other mastodons. A group of us started exploring that issue, trying to determine what was going on. To that end, in 2016 we launched a crowdfunding campaign on experiment.com to allow us to gather mastodon measurements from other parts of the continent. Exploring this problem continued through the Valley of the Mastodons symposium in 2017. Sometime in late 2017, we started to consider the possibility that we were seeing these differences because we were dealing with two different species, and by mid-2018 we started working on a manuscript. It was finally published last Wednesday.So, what makes the Pacific mastodon different from the American mastodon? Here are the major characters:-- Mammut pacificus has narrower teeth than M. americanum, especially the 3rd molars. On the left below is a lower third molar from Max, and on the right is the same tooth from an American mastodon from Ohio (from the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science).

The big news this week for Western Science Center was the naming of a new species of mastodon, Mammut pacificus.For decades, the consensus on Pleistocene mastodons (which I shared) was that in North America there was only a single, widespread species, Mammut americanum. Four years ago, I stumbled across the fact that California mastodons have different tooth proportions than other mastodons. A group of us started exploring that issue, trying to determine what was going on. To that end, in 2016 we launched a crowdfunding campaign on experiment.com to allow us to gather mastodon measurements from other parts of the continent. Exploring this problem continued through the Valley of the Mastodons symposium in 2017. Sometime in late 2017, we started to consider the possibility that we were seeing these differences because we were dealing with two different species, and by mid-2018 we started working on a manuscript. It was finally published last Wednesday.So, what makes the Pacific mastodon different from the American mastodon? Here are the major characters:-- Mammut pacificus has narrower teeth than M. americanum, especially the 3rd molars. On the left below is a lower third molar from Max, and on the right is the same tooth from an American mastodon from Ohio (from the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science). This trend is present in every tooth position except the upper 2nd molars, although we had the best statistical support for the 3rd molars.-- Mammut pacificus has six sacral vertebrae, while M. americanum usually has five. There has been one American mastodon reported with six sacrals, and another reported with four (although I have not personally seen either of these specimens), but all the other specimens for which we could get data (five of them) have five sacrals. All three known M. pacificus sacrals, including the one below from Diamond Valley Lake, have six.

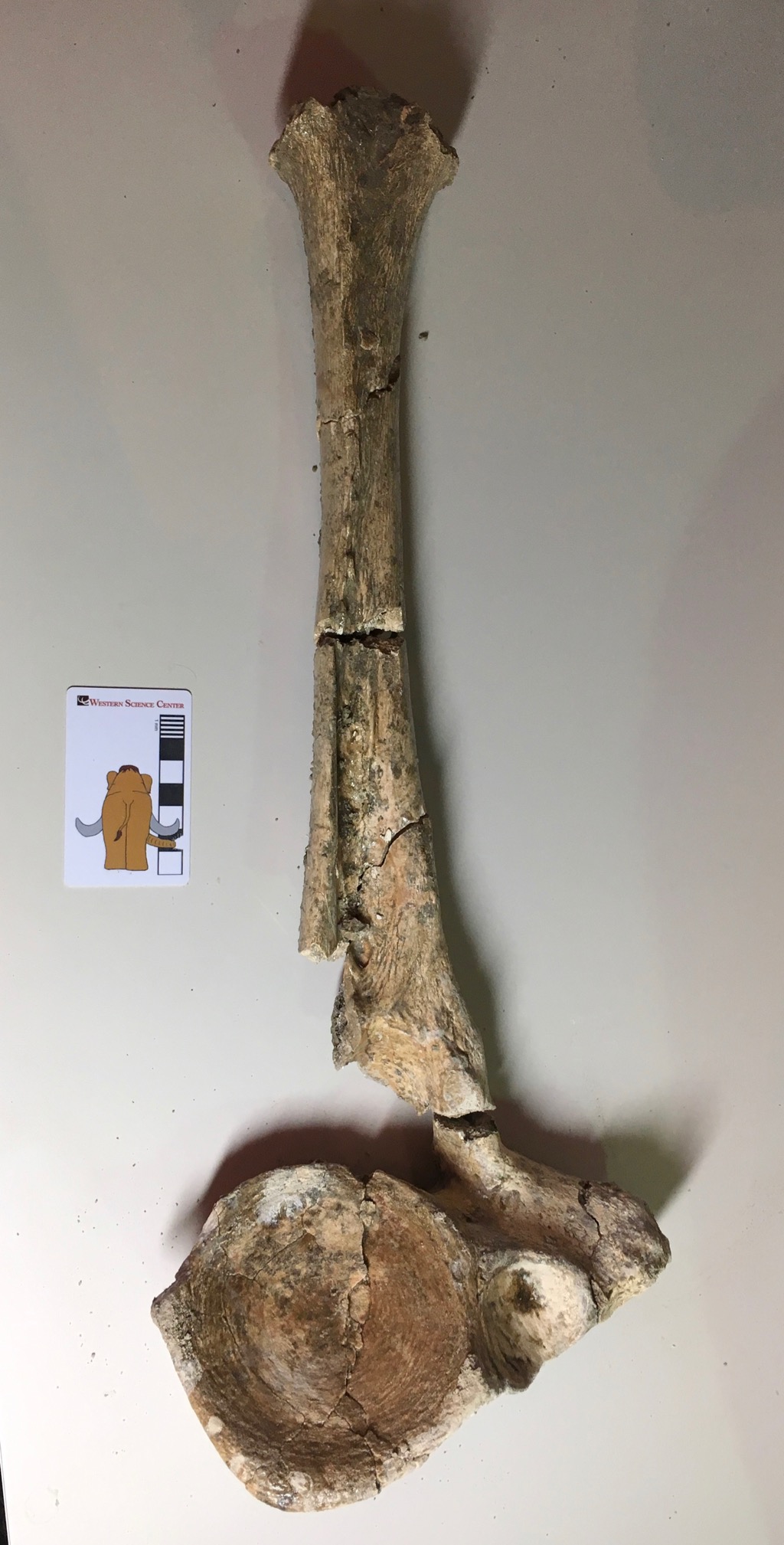

This trend is present in every tooth position except the upper 2nd molars, although we had the best statistical support for the 3rd molars.-- Mammut pacificus has six sacral vertebrae, while M. americanum usually has five. There has been one American mastodon reported with six sacrals, and another reported with four (although I have not personally seen either of these specimens), but all the other specimens for which we could get data (five of them) have five sacrals. All three known M. pacificus sacrals, including the one below from Diamond Valley Lake, have six. -- Mammut pacificus has a thicker femur for a given length. This is a feature we need to explore further, but our data is a bit limited. The trends we see suggest that not only do Pacific mastodons have thicker femora, but that the difference becomes more pronounced with larger body size. However, we don't have any really big M. pacificus femora to confirm this (Max's femur is incomplete). Below, "Little Stevie's" femur from DVL is on the left, compared to an American mastodon specimen from Ohio (again, from the Cincinnati Museum).

-- Mammut pacificus has a thicker femur for a given length. This is a feature we need to explore further, but our data is a bit limited. The trends we see suggest that not only do Pacific mastodons have thicker femora, but that the difference becomes more pronounced with larger body size. However, we don't have any really big M. pacificus femora to confirm this (Max's femur is incomplete). Below, "Little Stevie's" femur from DVL is on the left, compared to an American mastodon specimen from Ohio (again, from the Cincinnati Museum). -- Mammut pacificus has no mandibular tusks, while they still occurred in about 25% of the M. americanum population. This is a tricky character, because both taxa seem to have been losing their chin tusks (the presence of chin tusks is the primitive condition for mastodons). But it seems that Pacific mastodons got there first. Below, at the top is Max's lower jaw, and below is a lower jaw from Colorado (from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science).Below is a map from our paper showing all the known Mammut pacificus localities, as well as the Mammut americanum localities we used in this study (there are many, many additional American mastodon sites we didn't examine):

-- Mammut pacificus has no mandibular tusks, while they still occurred in about 25% of the M. americanum population. This is a tricky character, because both taxa seem to have been losing their chin tusks (the presence of chin tusks is the primitive condition for mastodons). But it seems that Pacific mastodons got there first. Below, at the top is Max's lower jaw, and below is a lower jaw from Colorado (from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science).Below is a map from our paper showing all the known Mammut pacificus localities, as well as the Mammut americanum localities we used in this study (there are many, many additional American mastodon sites we didn't examine): Note that, with the Oregon sample, we did not find any of the diagnostic bones (m3, femur, sacrum, lower jaw), so we conservatively coded the data as M. americanum, but it could actually be M. pacificus.We are committed to making our discovery as widely known as possible. To that end, we published our paper in the open access journal PeerJ, where it is available as a free download. We have also made 3D scans of 24 of the key DVL specimens available on MorphoSource and Sketchfab.I'll be writing more about the Pacific mastodon, but this is a quick summary of the highlights of the paper. If you really want to get into the details, our data is all available at the PeerJ link. Enjoy!

Note that, with the Oregon sample, we did not find any of the diagnostic bones (m3, femur, sacrum, lower jaw), so we conservatively coded the data as M. americanum, but it could actually be M. pacificus.We are committed to making our discovery as widely known as possible. To that end, we published our paper in the open access journal PeerJ, where it is available as a free download. We have also made 3D scans of 24 of the key DVL specimens available on MorphoSource and Sketchfab.I'll be writing more about the Pacific mastodon, but this is a quick summary of the highlights of the paper. If you really want to get into the details, our data is all available at the PeerJ link. Enjoy!

Fossil Friday - Zygolophodon tooth

Last week, I visited the Division of Fossil Primates at the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina. They have a great collection of fossil proboscideans from Egypt, including early forms like Moeritherium and Paleomastodon, as well as later, larger species such as Gomphotherium angustidens.I was there especially to see four teeth, the only known fossils of Zygolophodon aegyptensis. The genus Zygolophodon is long-lived and widespread, including many other species from Europe, Asia, and North America. At about 18 million years old, Z. aegyptensis is among the oldest. Zygolophodon is a member of the group Mammutidae, making it a close relative of North America's mastodons, including those found at Diamond Valley and housed at Western Science Center.The image here is DPC 12598, an upper molar (right M3) of Zygolophodon aegyptensis, and a left M3 of a mastodon from Diamond Valley (WSC-P-9970) set to the same scale. My Western Science Center colleagues and I are working with paleontologists at several other institutions to explore the whole evolutionary history of Mammutidae. Visiting other museums to examine fossils of other species and comparing them to the bounty of mastodons from Diamond Valley is one of the first steps on this journey.My thanks to Catherine Riddle of the Division of Fossil Primates for her assistance during my visit.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Last week, I visited the Division of Fossil Primates at the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina. They have a great collection of fossil proboscideans from Egypt, including early forms like Moeritherium and Paleomastodon, as well as later, larger species such as Gomphotherium angustidens.I was there especially to see four teeth, the only known fossils of Zygolophodon aegyptensis. The genus Zygolophodon is long-lived and widespread, including many other species from Europe, Asia, and North America. At about 18 million years old, Z. aegyptensis is among the oldest. Zygolophodon is a member of the group Mammutidae, making it a close relative of North America's mastodons, including those found at Diamond Valley and housed at Western Science Center.The image here is DPC 12598, an upper molar (right M3) of Zygolophodon aegyptensis, and a left M3 of a mastodon from Diamond Valley (WSC-P-9970) set to the same scale. My Western Science Center colleagues and I are working with paleontologists at several other institutions to explore the whole evolutionary history of Mammutidae. Visiting other museums to examine fossils of other species and comparing them to the bounty of mastodons from Diamond Valley is one of the first steps on this journey.My thanks to Catherine Riddle of the Division of Fossil Primates for her assistance during my visit.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - mastodon skull update

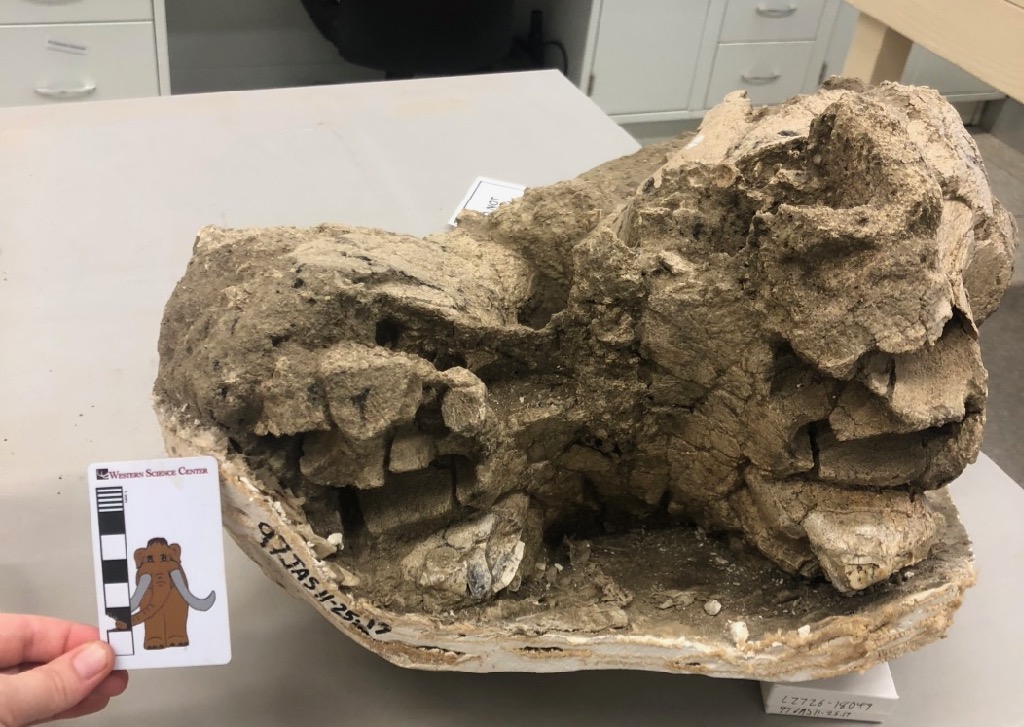

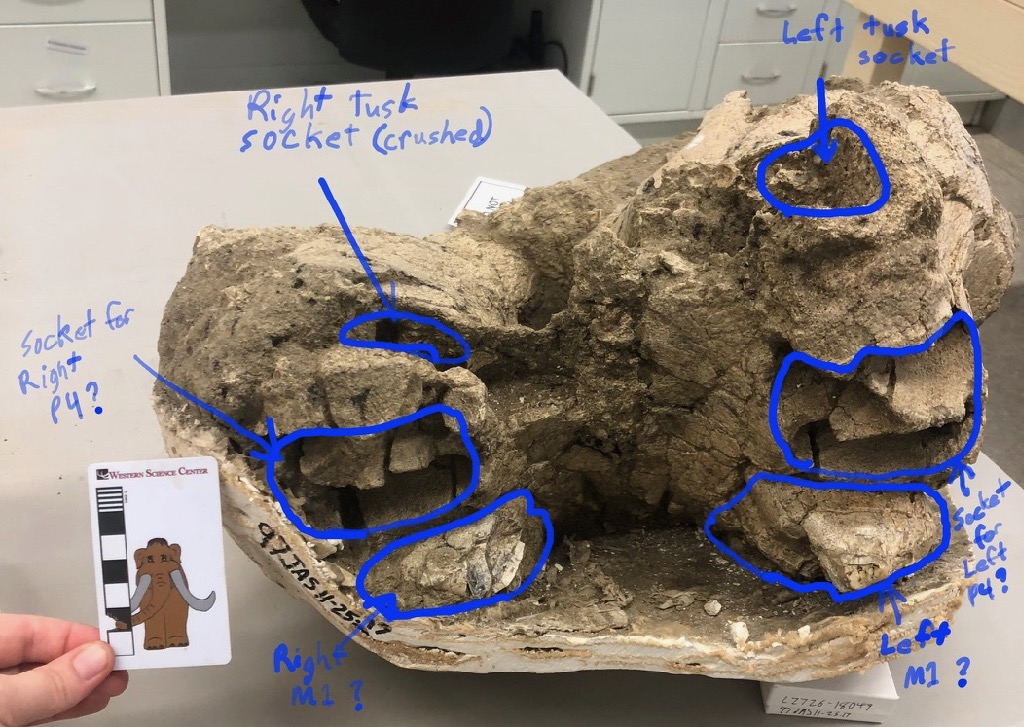

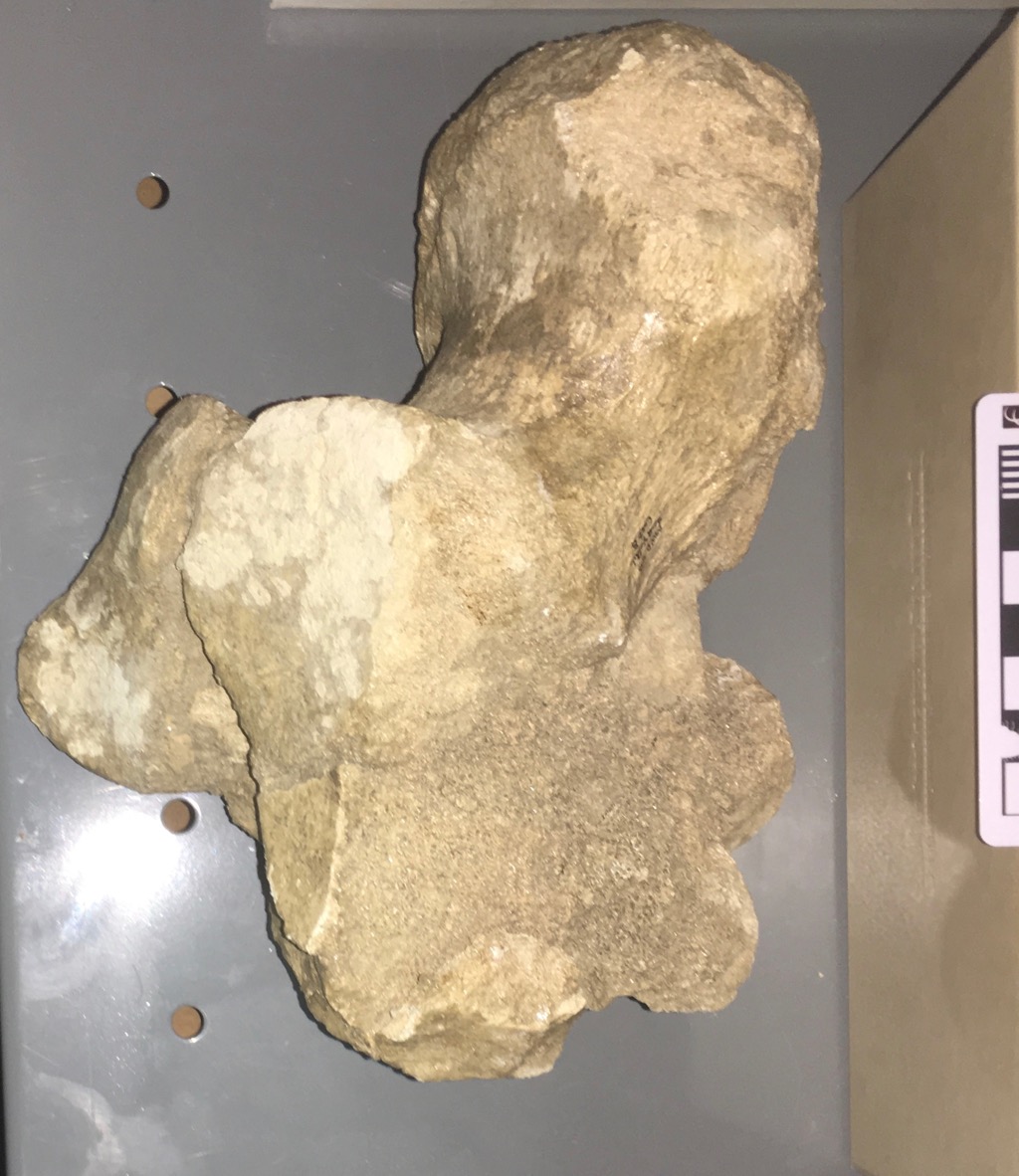

A few weeks ago I wrote about a mastodon skull we had moved into the lab for additional prep work. Kind of a lot has happened since then.We managed to successfully remove the remaining part of the original field jacket, which had bee on the skull since it was first found in 1997. That enabled us to turn the skull over and start working on the ventral side, where we could get a better view of the teeth.I speculated last week that this skull was almost certainly either a juvenile or a female, based on its small size and small tusk diameter (while the tusks aren't preserved, their sockets are). The determination between juvenile and female depended on whether or not the preserved tooth was the 1st molar (indicating a young animal) or the 2nd molar (indicating a young adult, and therefore probably a female). It turns out everyone was wrong!

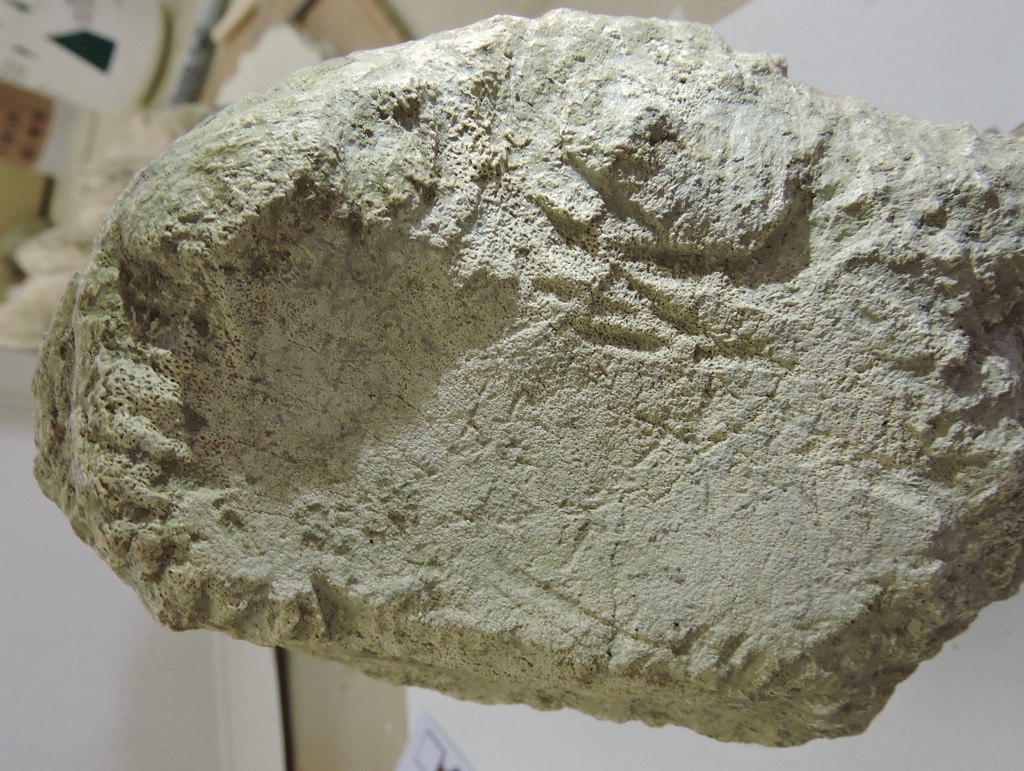

A few weeks ago I wrote about a mastodon skull we had moved into the lab for additional prep work. Kind of a lot has happened since then.We managed to successfully remove the remaining part of the original field jacket, which had bee on the skull since it was first found in 1997. That enabled us to turn the skull over and start working on the ventral side, where we could get a better view of the teeth.I speculated last week that this skull was almost certainly either a juvenile or a female, based on its small size and small tusk diameter (while the tusks aren't preserved, their sockets are). The determination between juvenile and female depended on whether or not the preserved tooth was the 1st molar (indicating a young animal) or the 2nd molar (indicating a young adult, and therefore probably a female). It turns out everyone was wrong! The teeth are outlined in blue above, with the empty tooth sockets outlined in blue. The teeth turned out to be 3rd molars, making the animal much older than I thought! The empty sockets, instead of being for the 4th premolars or 1st molars, were actually for the 2nd molars.The 3rd molars in this case were either unerupted or just starting to erupt; the 2nd molars probably fell out after death. That means this mastodon was probably between 25 and 30 years old when it died. Instead of the pre-teen or teenager I expected, this was a fully mature female mastodon, the first one identified from Diamond Valley Lake.We still have a bit more cleaning to do to the skull. Unfortunately, while there is a substantial amount of bone present behind the palate, it is completely splintered and probably can't be reconstructed. Even so, we'll be getting some good data from this specimen.

The teeth are outlined in blue above, with the empty tooth sockets outlined in blue. The teeth turned out to be 3rd molars, making the animal much older than I thought! The empty sockets, instead of being for the 4th premolars or 1st molars, were actually for the 2nd molars.The 3rd molars in this case were either unerupted or just starting to erupt; the 2nd molars probably fell out after death. That means this mastodon was probably between 25 and 30 years old when it died. Instead of the pre-teen or teenager I expected, this was a fully mature female mastodon, the first one identified from Diamond Valley Lake.We still have a bit more cleaning to do to the skull. Unfortunately, while there is a substantial amount of bone present behind the palate, it is completely splintered and probably can't be reconstructed. Even so, we'll be getting some good data from this specimen.

Fossil Friday - mastodon skull

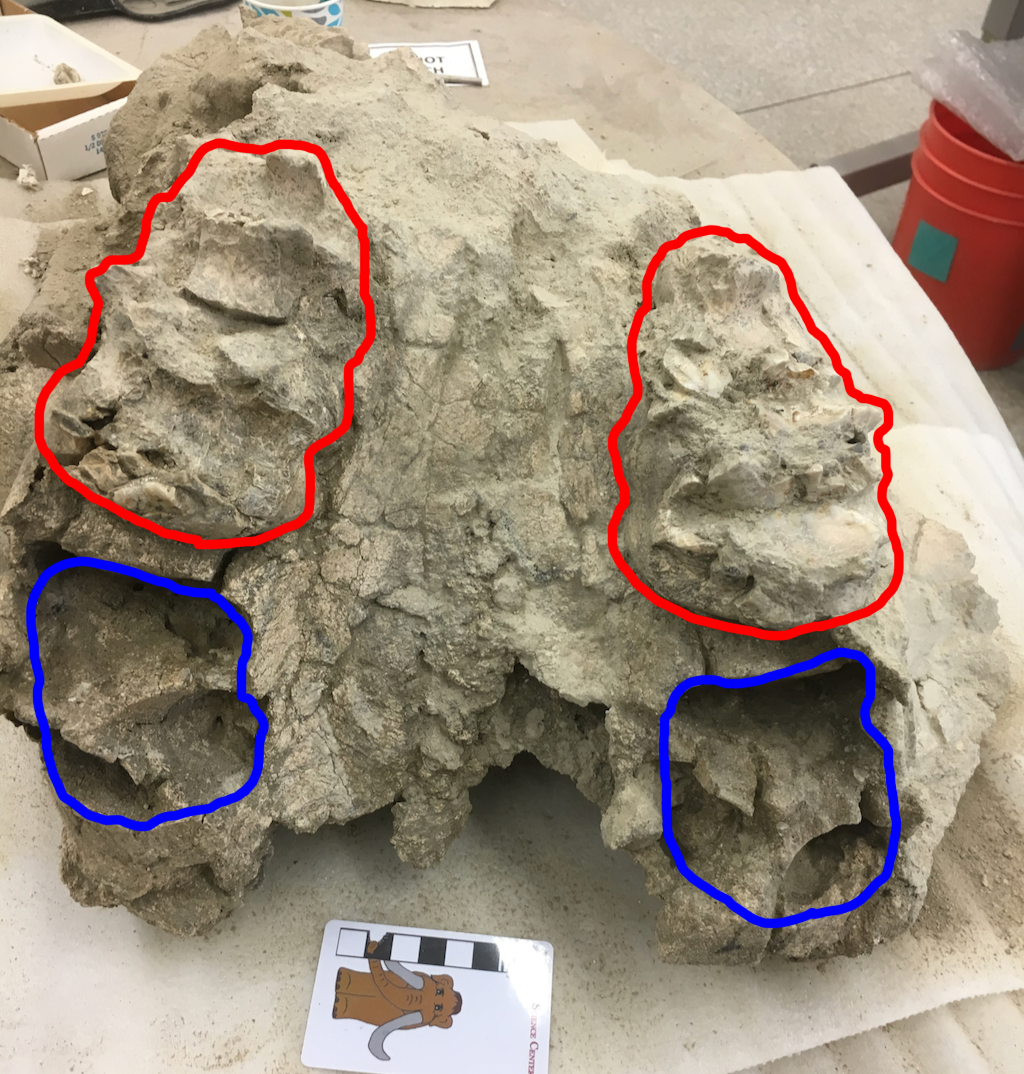

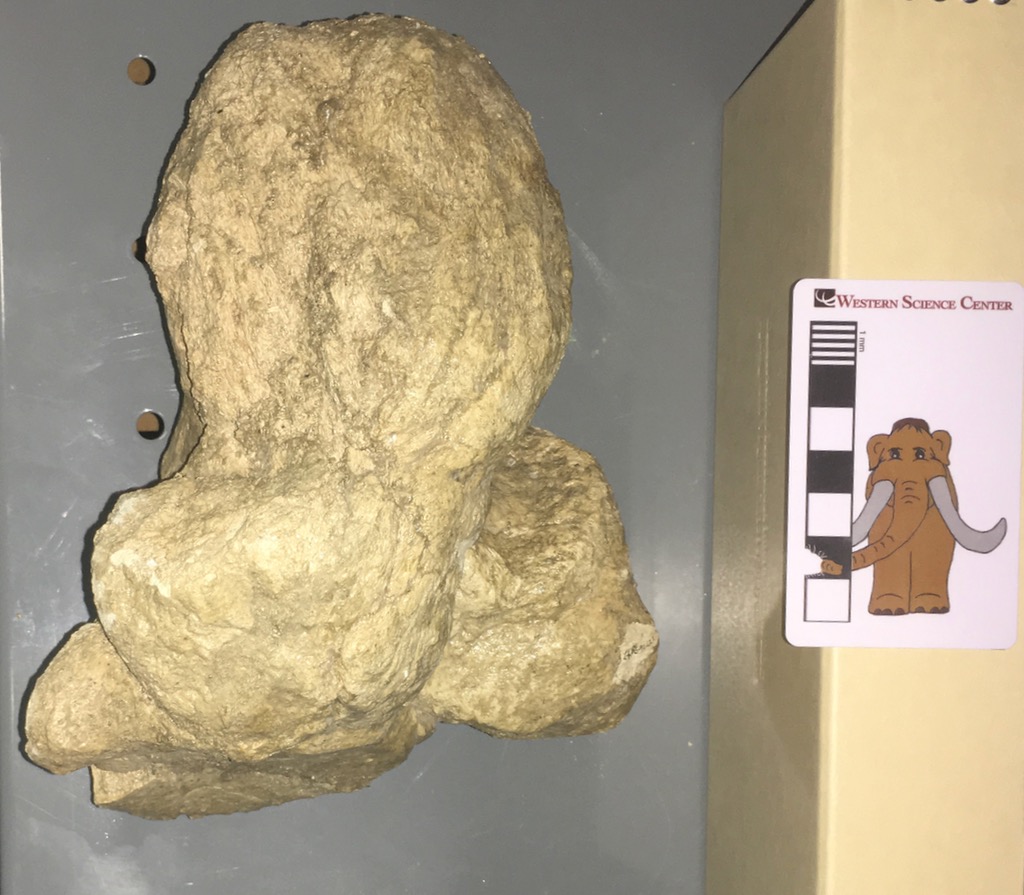

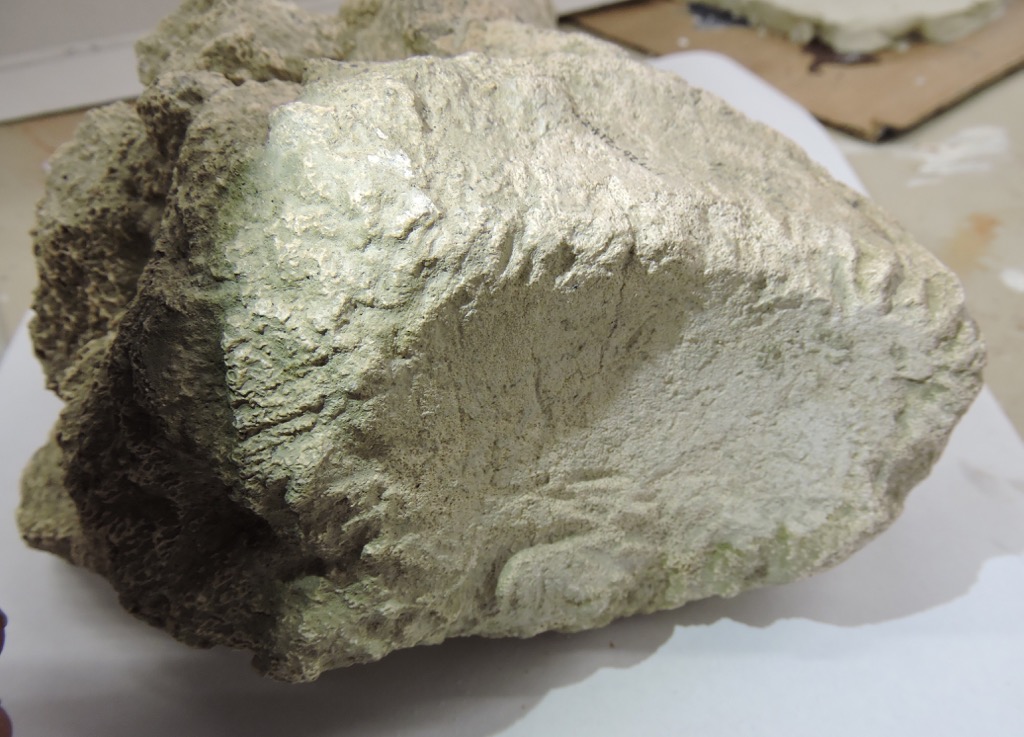

We haven't talked much about mastodons on the blog lately, but that doesn't mean they've been forgotten. We've been doing a lot of work scanning, measuring, and otherwise documenting the mastodons in our collection, and we're doing additional preparation work on some of them. The specimen featured in this week's post was moved into our preparation lab a few days ago for additional work.This may seem at first glance like a nondescript lump of bone, but it's actually a fairly significant amount of a small mastodon skull. This is an unusual view, looking head-on almost straight into the mouth. Below is an annotated version:

We haven't talked much about mastodons on the blog lately, but that doesn't mean they've been forgotten. We've been doing a lot of work scanning, measuring, and otherwise documenting the mastodons in our collection, and we're doing additional preparation work on some of them. The specimen featured in this week's post was moved into our preparation lab a few days ago for additional work.This may seem at first glance like a nondescript lump of bone, but it's actually a fairly significant amount of a small mastodon skull. This is an unusual view, looking head-on almost straight into the mouth. Below is an annotated version: So we actually have nearly the entire palate of this animal, as well as the tusk sockets. Unfortunately, we can't see the teeth clearly because obscured by the plaster jacket, which is why we've moved this into the lab. We're going to try removing the jacket and cleaning the ventral side of the skull. That should enable us to determine if the preserved teeth are in fact the first molars (as suggested in the annotation), or whether they're actually the second molars.Determining the identification of this tooth has broad implications for this specimen. If you noticed the scale bar, you might have realized that this is a very small skull for a mastodon. If the tooth is the 1st molar, that means this mastodon was only about 14-15 years old, a young adolescent. But if it's the 2nd molar, it means that the mastodon was more like 27-28 years old, a full grown adult. To be that small at that age, this would have to be a female (male mastodons are much larger than females).Both female and juvenile mastodons are exceptionally rare from Diamond Valley Lake. In fact, whichever this specimen turns out to be, it will be the only skull from DVL in that category. So, female or juvenile? As soon as we find out, we'll let you know in a future post.

So we actually have nearly the entire palate of this animal, as well as the tusk sockets. Unfortunately, we can't see the teeth clearly because obscured by the plaster jacket, which is why we've moved this into the lab. We're going to try removing the jacket and cleaning the ventral side of the skull. That should enable us to determine if the preserved teeth are in fact the first molars (as suggested in the annotation), or whether they're actually the second molars.Determining the identification of this tooth has broad implications for this specimen. If you noticed the scale bar, you might have realized that this is a very small skull for a mastodon. If the tooth is the 1st molar, that means this mastodon was only about 14-15 years old, a young adolescent. But if it's the 2nd molar, it means that the mastodon was more like 27-28 years old, a full grown adult. To be that small at that age, this would have to be a female (male mastodons are much larger than females).Both female and juvenile mastodons are exceptionally rare from Diamond Valley Lake. In fact, whichever this specimen turns out to be, it will be the only skull from DVL in that category. So, female or juvenile? As soon as we find out, we'll let you know in a future post.

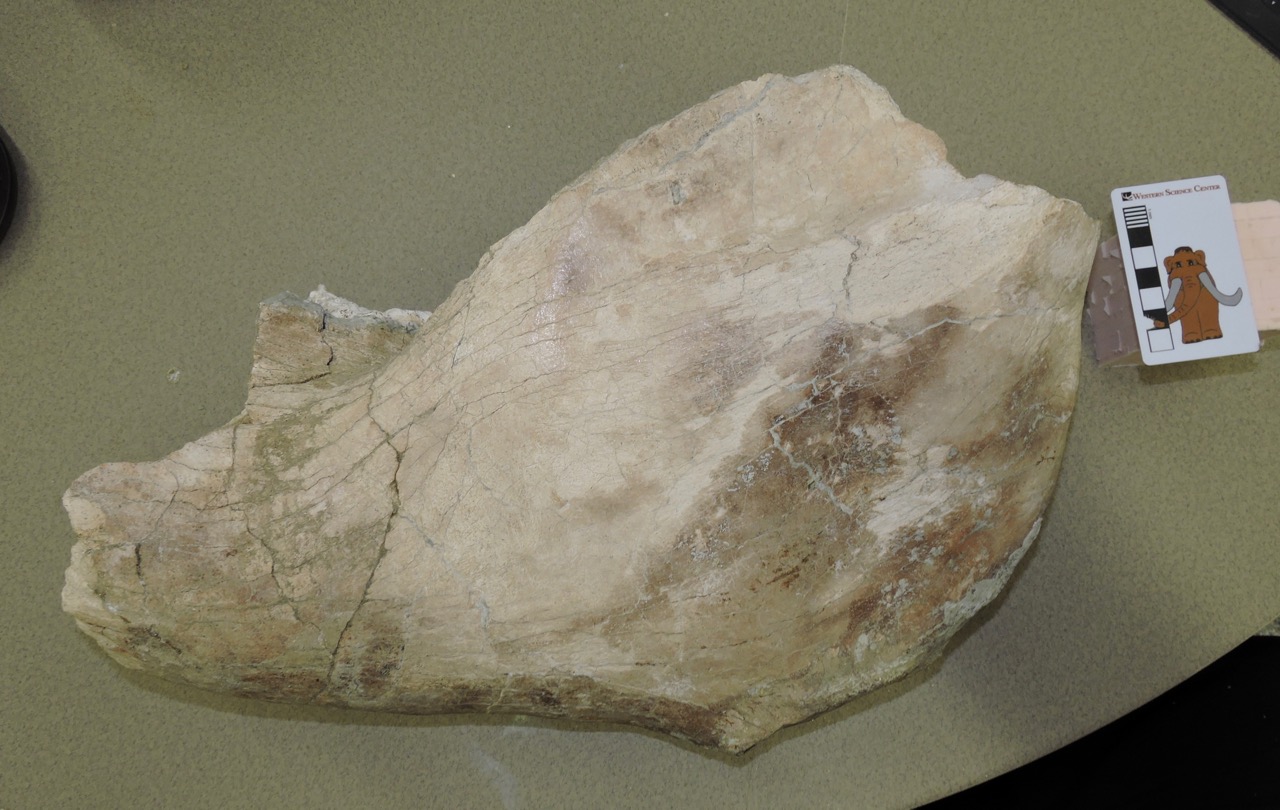

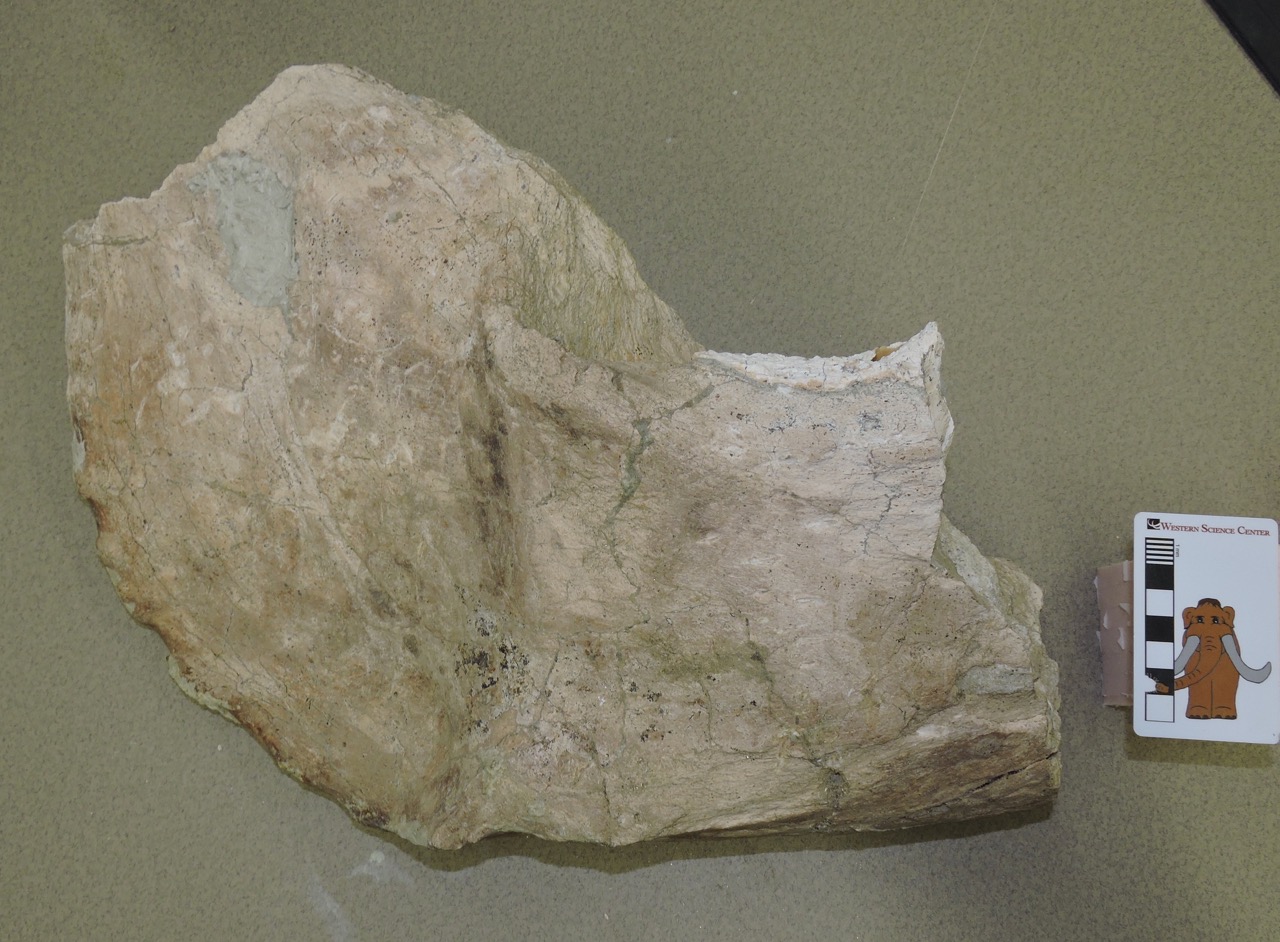

Fossil Friday - mastodon palate

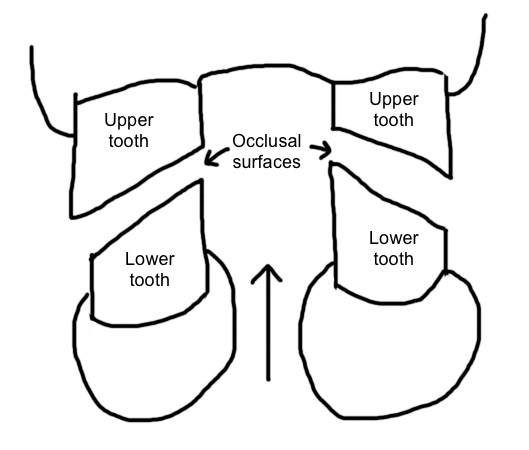

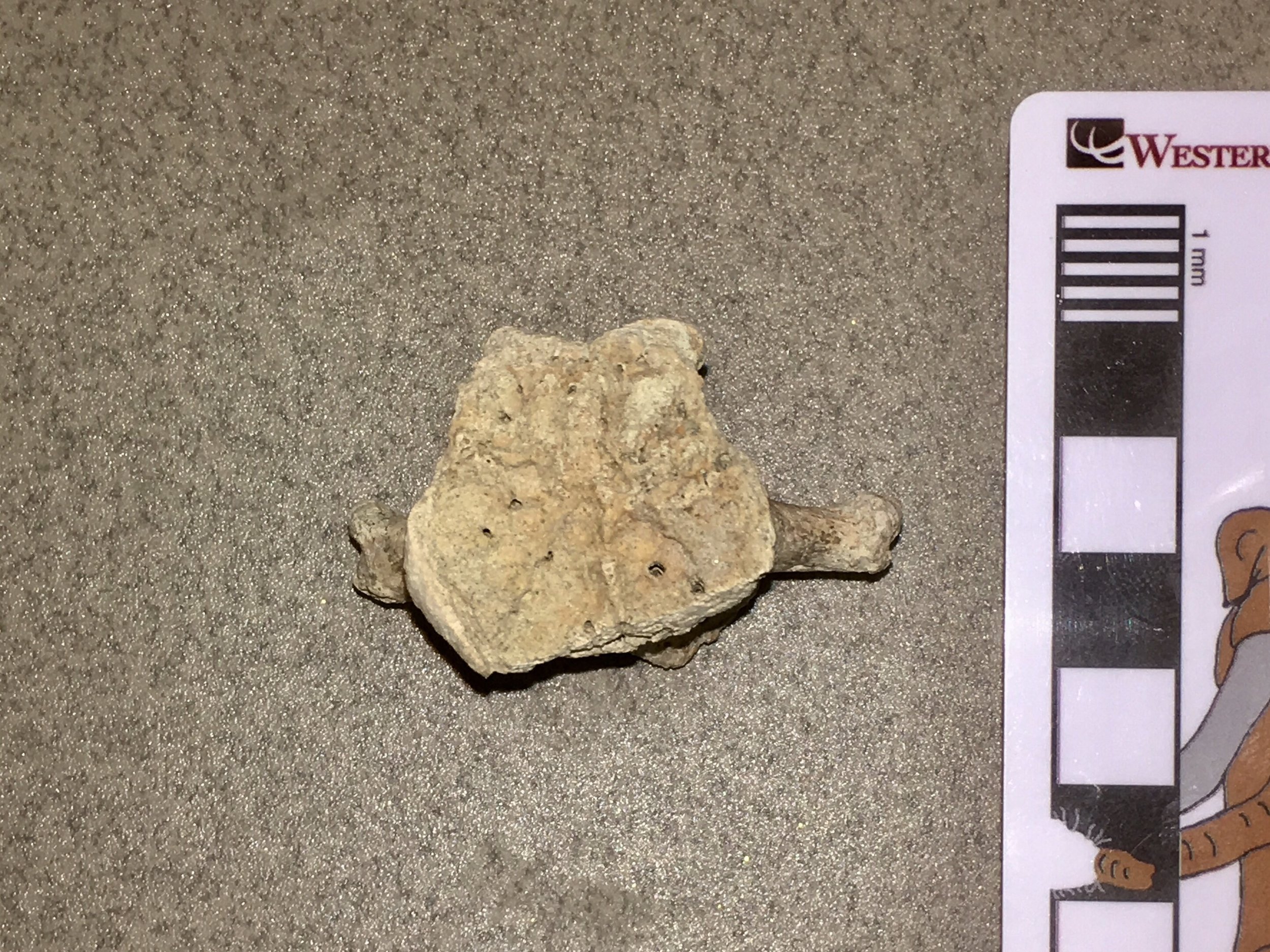

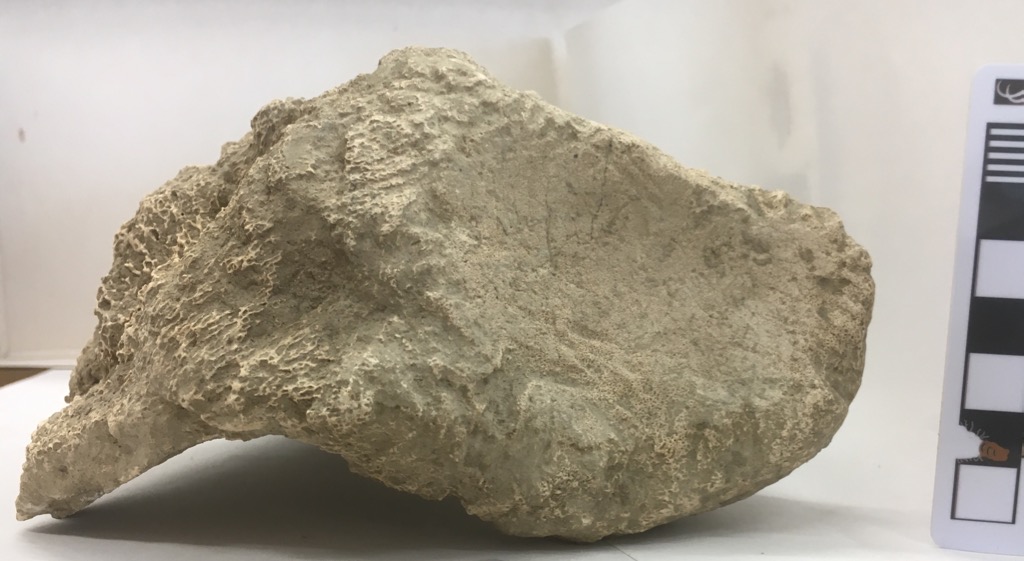

The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has closed, and most of out mastodon remains have been moved back to the museum's repository. But that doesn't mean they're forgotten, or that work on them has stopped!This specimen is a fragment of a mastodon palate, with the anterior end on the left. Most of the left side of the palate is missing, but the right side (at the bottom of the image) includes the complete 2nd and 3rd molars. Even a small fragment like this tells us quite a bit about mastodons.Like other advanced proboscideans, mastodons replaced their teeth horizontally instead of vertically like most mammals. That means that during the mastodon's life it gradually works it's way through six teeth in each quarter jaw, one after another - the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th premolars, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars (we're ignoring the tusks here, which are also teeth). With this pattern of tooth replacement, by looking at which teeth are present in the mouth and how worn the teeth are, we can make a reasonably precise estimate of how old the mastodon was when it died.In 1966, British biologist Richard Laws published a detailed description of how tooth wear and replacement rates relate to age in African elephants, which has become the standard starting point for estimating proboscidean ages. He divided the elephant life cycle into 30 tooth wear stages, which are now called Laws groups. So, for example, an African elephant with the 4th premolar heavily worn and the 1st molar just about to erupt would be in Laws group VII, which would make it 6 years old, ± 1 year.With some limitations, this same system works pretty well for mastodons even though they're only distantly related to elephants. Because there is some uncertainty involved, when applied to extinct elephants the age indicated by the Laws group is usually expressed in terms of AEY (African Equivalent Years), the age that an African elephant would be in the same wear state.So how about this mastodon? The 2nd molar is still present, but is almost completely worn away; there is only a thin band of enamel remaining around the edges. The 3rd molar shows lots of wear on the 1st loph at the front of the tooth, somewhat less on the 2nd loph, light wear on the 3rd, and little or no wear on the 4th. That puts this mastodon into Laws group 22, with an age of 39 ± 2 AEY, a fully mature but not yet elderly mastodon. We actually have several mastodons from Diamond Valley Lake that fall into Laws group 22, including Max, our largest and best-preserved skull.This particular mastodon was discovered at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, making it between about 14,000-20,000 years old. Reference:Laws, R. M., 1966. Age criteria for the African elephant, Loxodonta a. africana. East African Wildlife Journal 4:1-37.

The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has closed, and most of out mastodon remains have been moved back to the museum's repository. But that doesn't mean they're forgotten, or that work on them has stopped!This specimen is a fragment of a mastodon palate, with the anterior end on the left. Most of the left side of the palate is missing, but the right side (at the bottom of the image) includes the complete 2nd and 3rd molars. Even a small fragment like this tells us quite a bit about mastodons.Like other advanced proboscideans, mastodons replaced their teeth horizontally instead of vertically like most mammals. That means that during the mastodon's life it gradually works it's way through six teeth in each quarter jaw, one after another - the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th premolars, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars (we're ignoring the tusks here, which are also teeth). With this pattern of tooth replacement, by looking at which teeth are present in the mouth and how worn the teeth are, we can make a reasonably precise estimate of how old the mastodon was when it died.In 1966, British biologist Richard Laws published a detailed description of how tooth wear and replacement rates relate to age in African elephants, which has become the standard starting point for estimating proboscidean ages. He divided the elephant life cycle into 30 tooth wear stages, which are now called Laws groups. So, for example, an African elephant with the 4th premolar heavily worn and the 1st molar just about to erupt would be in Laws group VII, which would make it 6 years old, ± 1 year.With some limitations, this same system works pretty well for mastodons even though they're only distantly related to elephants. Because there is some uncertainty involved, when applied to extinct elephants the age indicated by the Laws group is usually expressed in terms of AEY (African Equivalent Years), the age that an African elephant would be in the same wear state.So how about this mastodon? The 2nd molar is still present, but is almost completely worn away; there is only a thin band of enamel remaining around the edges. The 3rd molar shows lots of wear on the 1st loph at the front of the tooth, somewhat less on the 2nd loph, light wear on the 3rd, and little or no wear on the 4th. That puts this mastodon into Laws group 22, with an age of 39 ± 2 AEY, a fully mature but not yet elderly mastodon. We actually have several mastodons from Diamond Valley Lake that fall into Laws group 22, including Max, our largest and best-preserved skull.This particular mastodon was discovered at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, making it between about 14,000-20,000 years old. Reference:Laws, R. M., 1966. Age criteria for the African elephant, Loxodonta a. africana. East African Wildlife Journal 4:1-37.

Fossil Friday - strange mastodon vertebrae

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however).

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however). The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

Fossil Friday - printed mastodon molar

Each September, Western Science Center holds an annual fundraiser called Science Under the Stars to raise funds for museum operations. At the end of the evening we often do a final “Special Ask” to raise dedicated funds for a particular project. This year, for the Special Ask we requested funds for a 3D-scanning, photogrammetry, and printing lab. Our donors, led by the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians, came through in spectacular fashion.

Each September, Western Science Center holds an annual fundraiser called Science Under the Stars to raise funds for museum operations. At the end of the evening we often do a final “Special Ask” to raise dedicated funds for a particular project. This year, for the Special Ask we requested funds for a 3D-scanning, photogrammetry, and printing lab. Our donors, led by the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians, came through in spectacular fashion.  Our first purchase for the lab, a LulzBot TAZ6 printer (above), arrived last week. After our initial demo print to make sure everything was working, our first specimen print was a mastodon tooth (of course). It was printed from a digitial file provided to us by VCU’s Virtual Curation Lab, courtesy of Bernard Means and Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt, which was in turn based on CT scans provided by California Imaging and Diagnostics. The particular tooth is the lower right 3rd molar of a West Dam mastodon we refer to as The Outlier, so named because its 3rd molars are the widest ones known from California (although still narrower than the average m3 from the rest of the country).In a few weeks we’ll be purchasing our scanning and photogrammetry equipment, as well as additional printers, so you’ll be hearing a lot more about this in the months ahead. Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America meeting, where Brett and I will be presenting on both the “Stepping Out of the Past” and the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits, and I’ll have updates from there as well.

Our first purchase for the lab, a LulzBot TAZ6 printer (above), arrived last week. After our initial demo print to make sure everything was working, our first specimen print was a mastodon tooth (of course). It was printed from a digitial file provided to us by VCU’s Virtual Curation Lab, courtesy of Bernard Means and Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt, which was in turn based on CT scans provided by California Imaging and Diagnostics. The particular tooth is the lower right 3rd molar of a West Dam mastodon we refer to as The Outlier, so named because its 3rd molars are the widest ones known from California (although still narrower than the average m3 from the rest of the country).In a few weeks we’ll be purchasing our scanning and photogrammetry equipment, as well as additional printers, so you’ll be hearing a lot more about this in the months ahead. Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America meeting, where Brett and I will be presenting on both the “Stepping Out of the Past” and the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits, and I’ll have updates from there as well.

Fossil Friday - mastodon vertebra revisited

After a highly successful Science Under the Stars fundraiser, I've tried to get back into the lab to catch up on neglected science work. Administrative duties are still conspiring to keep me chained to the phone and computer, but I have made some progress.Above is a mastodon thoracic vertebrae, one of the same vertebrae featured on Fossil Friday last month. We've removed this vertebra from the field jacket and started repairs and reconstruction.The image above is in posterior view, with anterior to the top. This is an anterior thoracic, with the very tall neural spine typical of that part of the skeleton. There are two prominent articulations on the right side for ribs. One is just below the tip of the transverse process and faces toward the lower right, while the other is the circular depression between the transverse process and the centrum. These two regions actually articulate with different ribs; the transverse process articulates with the tuberculum (or tubercle) of the rib, while the depression adjacent to the centrum articulates with the capitulum (or head) of the next rib.We'll continue cleaning this and the other bones from this jacket in the coming weeks. We should be able to pin down pretty tightly which vertebra in the series this is. Then these will be joining other bones from the same individual in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit.

After a highly successful Science Under the Stars fundraiser, I've tried to get back into the lab to catch up on neglected science work. Administrative duties are still conspiring to keep me chained to the phone and computer, but I have made some progress.Above is a mastodon thoracic vertebrae, one of the same vertebrae featured on Fossil Friday last month. We've removed this vertebra from the field jacket and started repairs and reconstruction.The image above is in posterior view, with anterior to the top. This is an anterior thoracic, with the very tall neural spine typical of that part of the skeleton. There are two prominent articulations on the right side for ribs. One is just below the tip of the transverse process and faces toward the lower right, while the other is the circular depression between the transverse process and the centrum. These two regions actually articulate with different ribs; the transverse process articulates with the tuberculum (or tubercle) of the rib, while the depression adjacent to the centrum articulates with the capitulum (or head) of the next rib.We'll continue cleaning this and the other bones from this jacket in the coming weeks. We should be able to pin down pretty tightly which vertebra in the series this is. Then these will be joining other bones from the same individual in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit.

Fossil Friday - mastodon vertebrae

Even though the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit is now open, it doesn't mean that our mastodon work has moved to the backburner. On the contrary, we're now doing more mastodon work than ever before!The field jacket shown above is associated with a partial mastodon skeleton currently on display in Valley of the Mastodons; I've previously featured the axis vertebra and the tusks from this mastodon on Fossil Fridays. This jacket has been partially prepared, but there are still several bones present. Some of these are highlighted in the color-coded version below:

Even though the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit is now open, it doesn't mean that our mastodon work has moved to the backburner. On the contrary, we're now doing more mastodon work than ever before!The field jacket shown above is associated with a partial mastodon skeleton currently on display in Valley of the Mastodons; I've previously featured the axis vertebra and the tusks from this mastodon on Fossil Fridays. This jacket has been partially prepared, but there are still several bones present. Some of these are highlighted in the color-coded version below: The blue area is (I think) the first cervical vertebra, or atlas. Yellow is a rib, and red are two thoracic vertebrae. There are also several unmarked and unidentified fragments. The thoracic vertebrae have the very tall neural spines that are typical of anterior thoracics in animals with large, heavy heads.We'll be removing these bones over the next few weeks, and as they're completed they'll be moving into the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit along with the rest of this mastodon.Next week I'll be in Calgary, attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting. Many paleontologists will be live-tweeting the conference, including me (at least on occasion) and @MaxMastodon.

The blue area is (I think) the first cervical vertebra, or atlas. Yellow is a rib, and red are two thoracic vertebrae. There are also several unmarked and unidentified fragments. The thoracic vertebrae have the very tall neural spines that are typical of anterior thoracics in animals with large, heavy heads.We'll be removing these bones over the next few weeks, and as they're completed they'll be moving into the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit along with the rest of this mastodon.Next week I'll be in Calgary, attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting. Many paleontologists will be live-tweeting the conference, including me (at least on occasion) and @MaxMastodon.

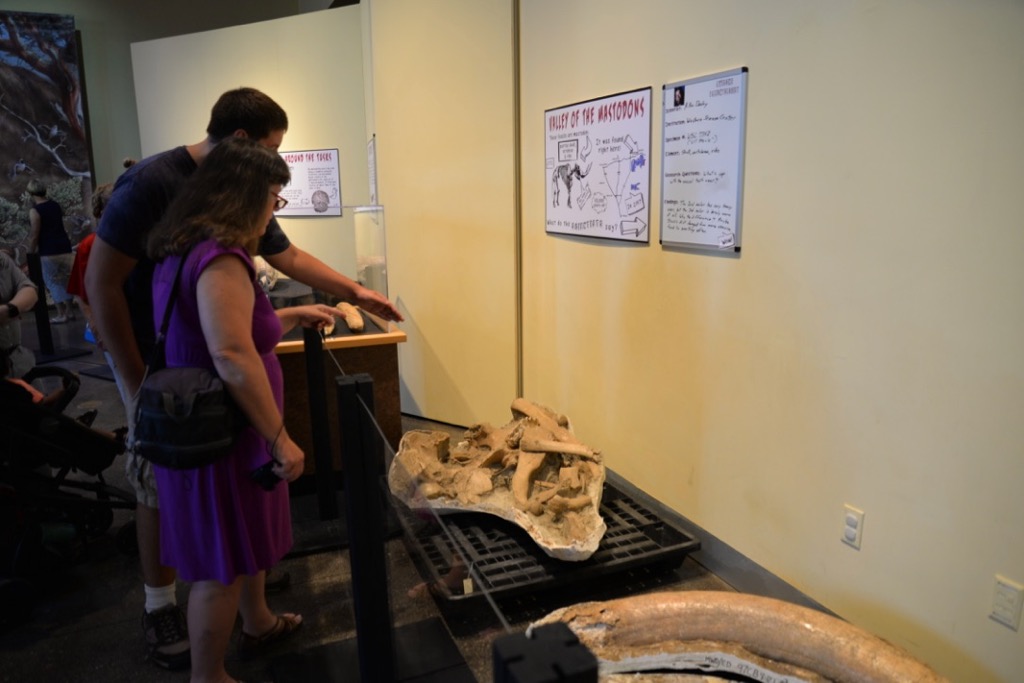

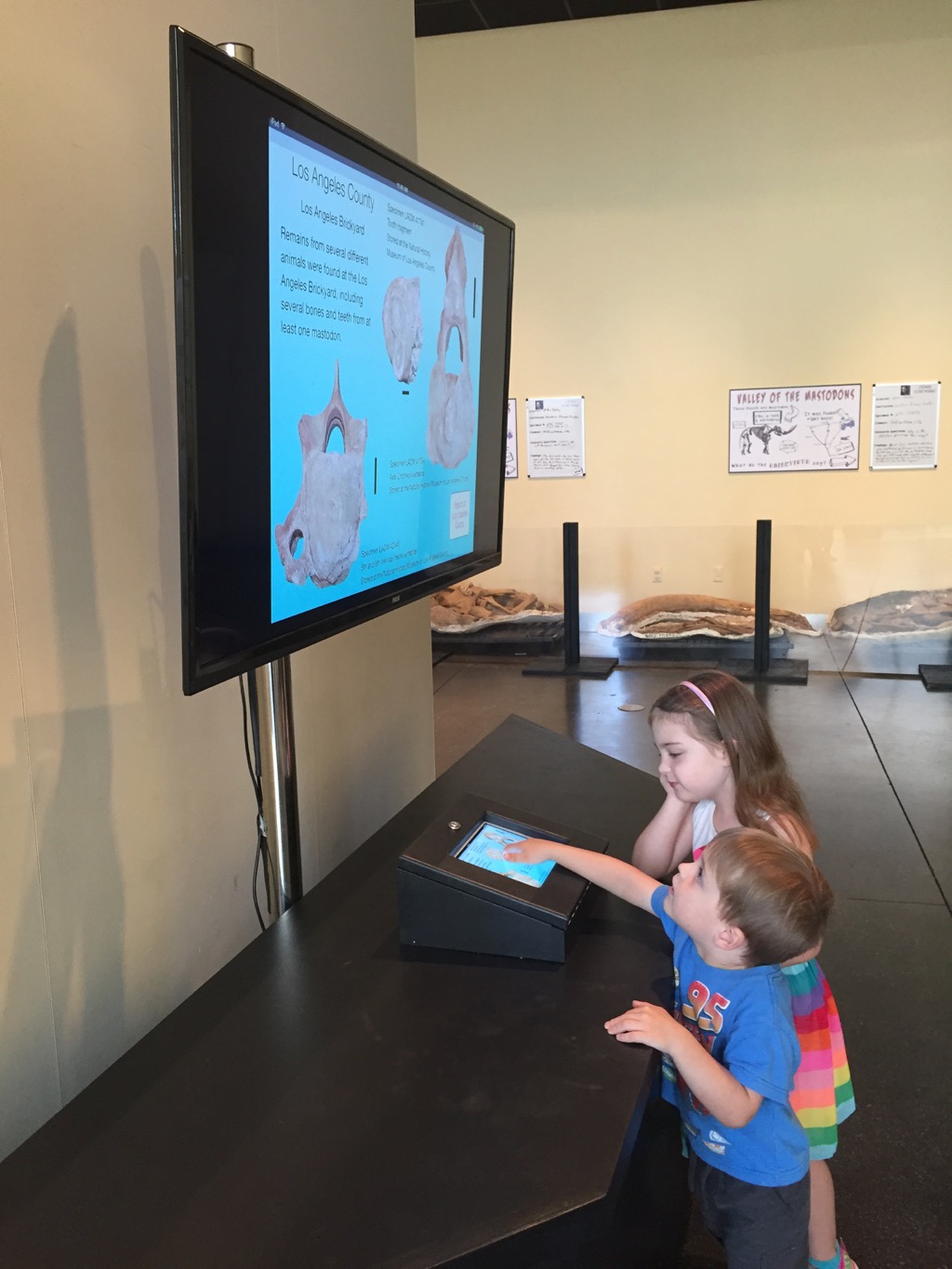

Valley of the Mastodons

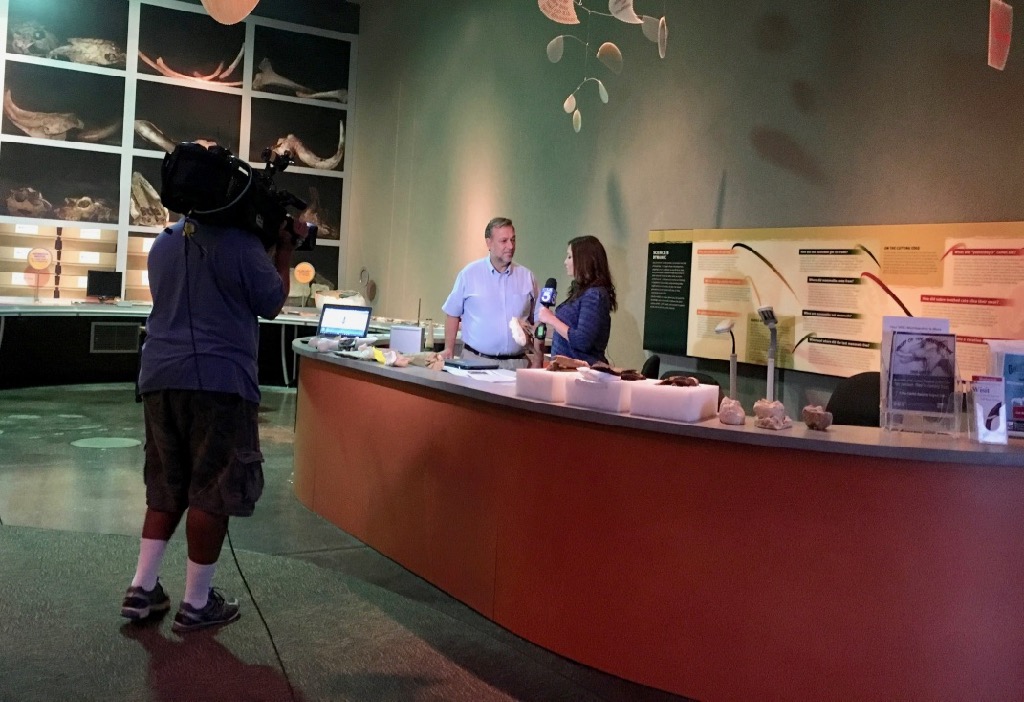

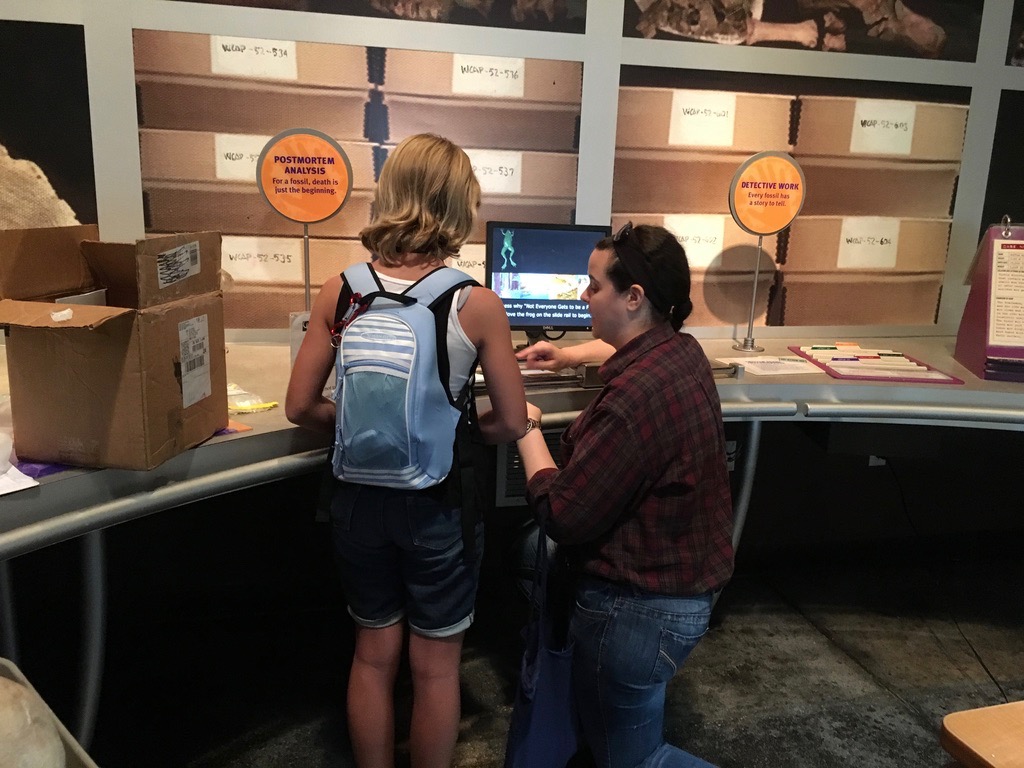

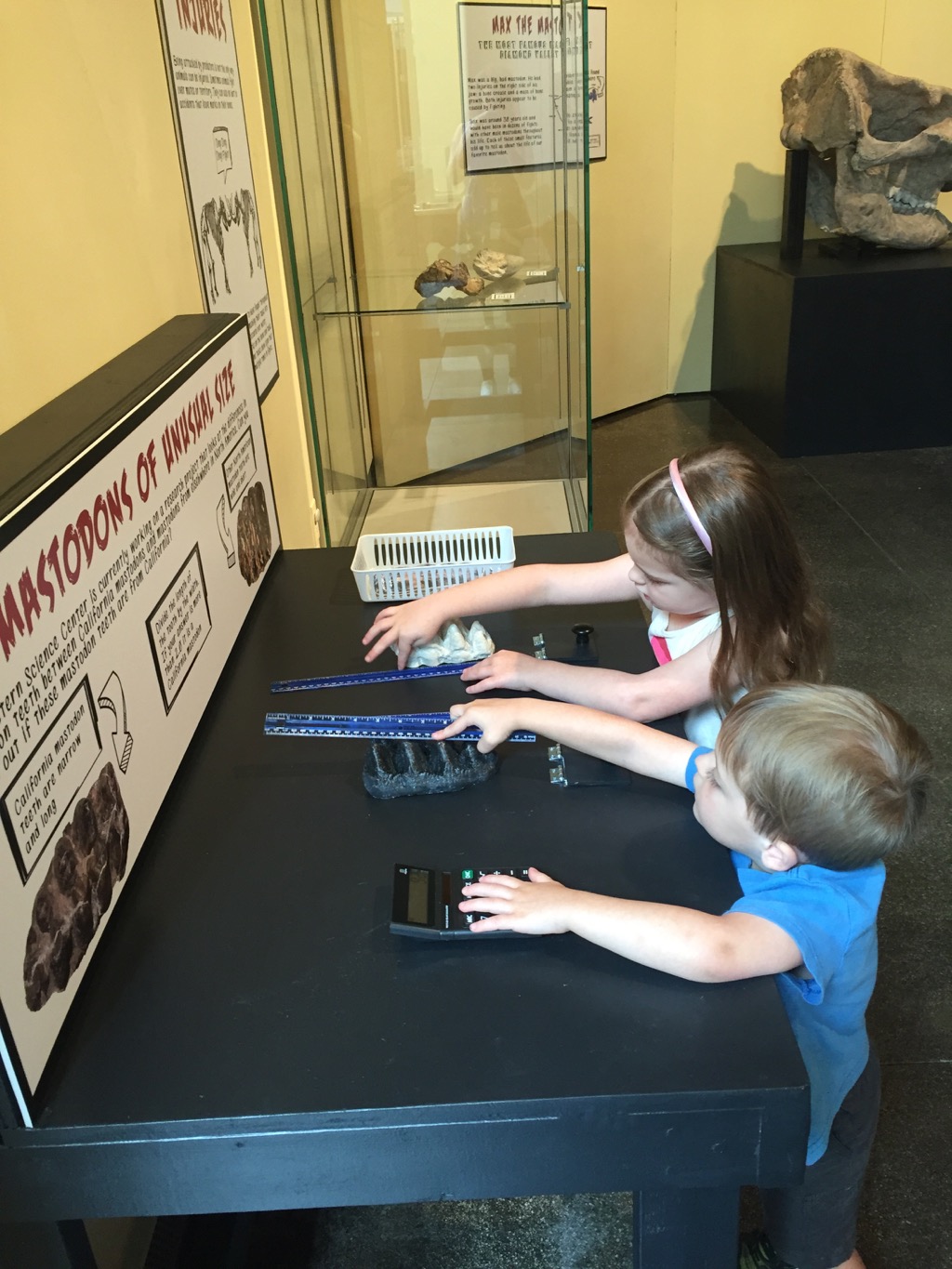

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

Fossil Friday - mastodon tusks

In three days scientists start arriving in Hemet for the Valley of the Mastodons symposium, and we're one week from the opening of the associated Valley of the Mastodons exhibit. As a result, I'm a little swamped, and today's Fossil Friday post will have to be brief.The original plan for Valley of the Mastodons was to display all of the mastodon material recovered from Diamond Valley Lake. That plan didn't last long. Our temporary exhibit gallery is 3,000 square feet, and while that's a pretty big room, we have a LOT of mastodons! It didn't take long to realize that they won't all fit. So we had to triage the collection, and things that have really cruddy preservation, and isolated bones that we can't say much about, are not going on display.One of the specimens that did make the cut is a partial mastodon from the West Dam, the area with the highest concentration of mastodons. This partial skeleton includes several ribs and vertebrae (a few weeks ago I featured its axis vertebra), a lower jaw fragment, a humerus, and both tusks. The tusks are shown above. They're reasonably well preserved, and include the open pulp cavities at the proximal ends (filled with sediment). The tips had crumbled a bit and are incomplete, but it doesn't look like too much is missing. The size of these tusks indicate that this was an adult male mastodon, although the unfused epiphyses on several vertebrae show that it wasn't quite finished growing.This mastodon and more than a dozen others will be on display beginning August 5 (WSC members are invited to a preview showing on August 4).

In three days scientists start arriving in Hemet for the Valley of the Mastodons symposium, and we're one week from the opening of the associated Valley of the Mastodons exhibit. As a result, I'm a little swamped, and today's Fossil Friday post will have to be brief.The original plan for Valley of the Mastodons was to display all of the mastodon material recovered from Diamond Valley Lake. That plan didn't last long. Our temporary exhibit gallery is 3,000 square feet, and while that's a pretty big room, we have a LOT of mastodons! It didn't take long to realize that they won't all fit. So we had to triage the collection, and things that have really cruddy preservation, and isolated bones that we can't say much about, are not going on display.One of the specimens that did make the cut is a partial mastodon from the West Dam, the area with the highest concentration of mastodons. This partial skeleton includes several ribs and vertebrae (a few weeks ago I featured its axis vertebra), a lower jaw fragment, a humerus, and both tusks. The tusks are shown above. They're reasonably well preserved, and include the open pulp cavities at the proximal ends (filled with sediment). The tips had crumbled a bit and are incomplete, but it doesn't look like too much is missing. The size of these tusks indicate that this was an adult male mastodon, although the unfused epiphyses on several vertebrae show that it wasn't quite finished growing.This mastodon and more than a dozen others will be on display beginning August 5 (WSC members are invited to a preview showing on August 4).

Fossil Friday - mastodon jaw fragment

As we build up to our new exhibit opening, I'll continue the Month of Mastodons with a partial lower jaw.This is the back end of the left dentary, seen in lateral view with anterior to the left. The front half of the bone is missing, as are the coronoid process and condyle that should be located at the posterodorsal edge (upper right in the photo). The tooth crown is also broken. Below is a medial view of the same bone:

As we build up to our new exhibit opening, I'll continue the Month of Mastodons with a partial lower jaw.This is the back end of the left dentary, seen in lateral view with anterior to the left. The front half of the bone is missing, as are the coronoid process and condyle that should be located at the posterodorsal edge (upper right in the photo). The tooth crown is also broken. Below is a medial view of the same bone: And here's the dorsal view:

And here's the dorsal view: In this view the broken tooth is more clearly visible. Even though the crown is broken off, the distinctive mastodon tooth shape is clear.Unlike the vast majority of mastodons in the Western Science Center collections, this jaw is not from Diamond Valley Lake. Instead, it was collected from the Grizzly Ridge section of Murrieta, about 20 km southwest of Diamond Valley Lake (still in Riverside County). This specimen came in as part of a mitigation project, and unfortunately included almost no data except for the locality name. Both early and late Pleistocene deposits are known from Murrieta, so we're not yet sure of the age.We have not yet begun preparation of this specimen, but a quick survey indicates that a substantial part of the skeleton was recovered, including at least some vertebrae, numerous ribs, multiple limb elements, and several tusk fragments. We're hoping to prepare the specimen over the next year or so in our new Exploration Station prep area in our main exhibit gallery. The dentary fragment will also be on exhibit during Valley of the Mastodons, opening to the public on August 5.

In this view the broken tooth is more clearly visible. Even though the crown is broken off, the distinctive mastodon tooth shape is clear.Unlike the vast majority of mastodons in the Western Science Center collections, this jaw is not from Diamond Valley Lake. Instead, it was collected from the Grizzly Ridge section of Murrieta, about 20 km southwest of Diamond Valley Lake (still in Riverside County). This specimen came in as part of a mitigation project, and unfortunately included almost no data except for the locality name. Both early and late Pleistocene deposits are known from Murrieta, so we're not yet sure of the age.We have not yet begun preparation of this specimen, but a quick survey indicates that a substantial part of the skeleton was recovered, including at least some vertebrae, numerous ribs, multiple limb elements, and several tusk fragments. We're hoping to prepare the specimen over the next year or so in our new Exploration Station prep area in our main exhibit gallery. The dentary fragment will also be on exhibit during Valley of the Mastodons, opening to the public on August 5.

Fossil Friday - mastodon partial skull

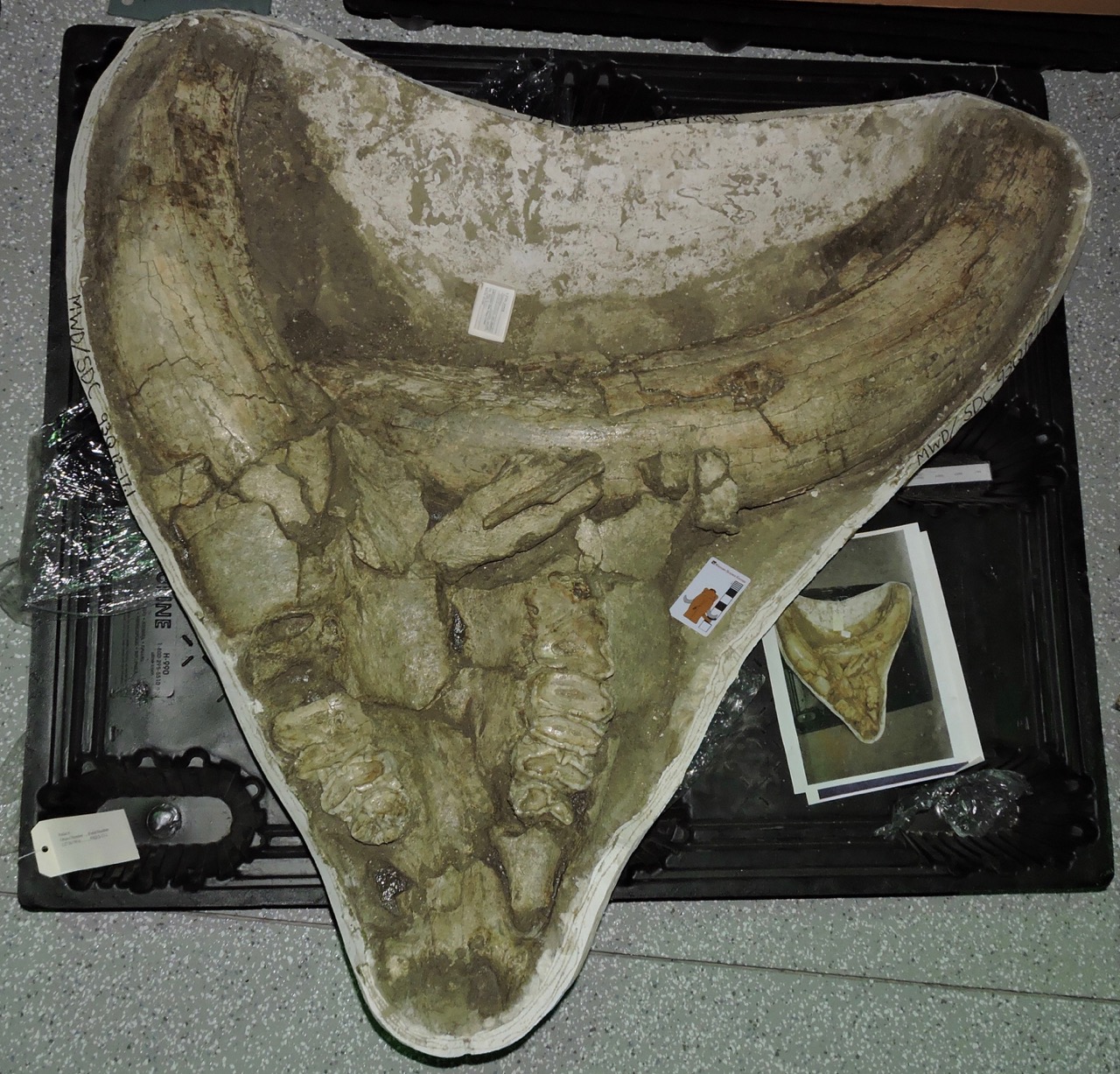

Our latest mastodon installment as we approach the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit opening 3 weeks from now is "Braces", a partial mastodon skull from the San Diego Canal."Braces" is still in his field jacket, with the ventral side exposed (and the large tusks do indicate that he's male). Below is an annotated version:

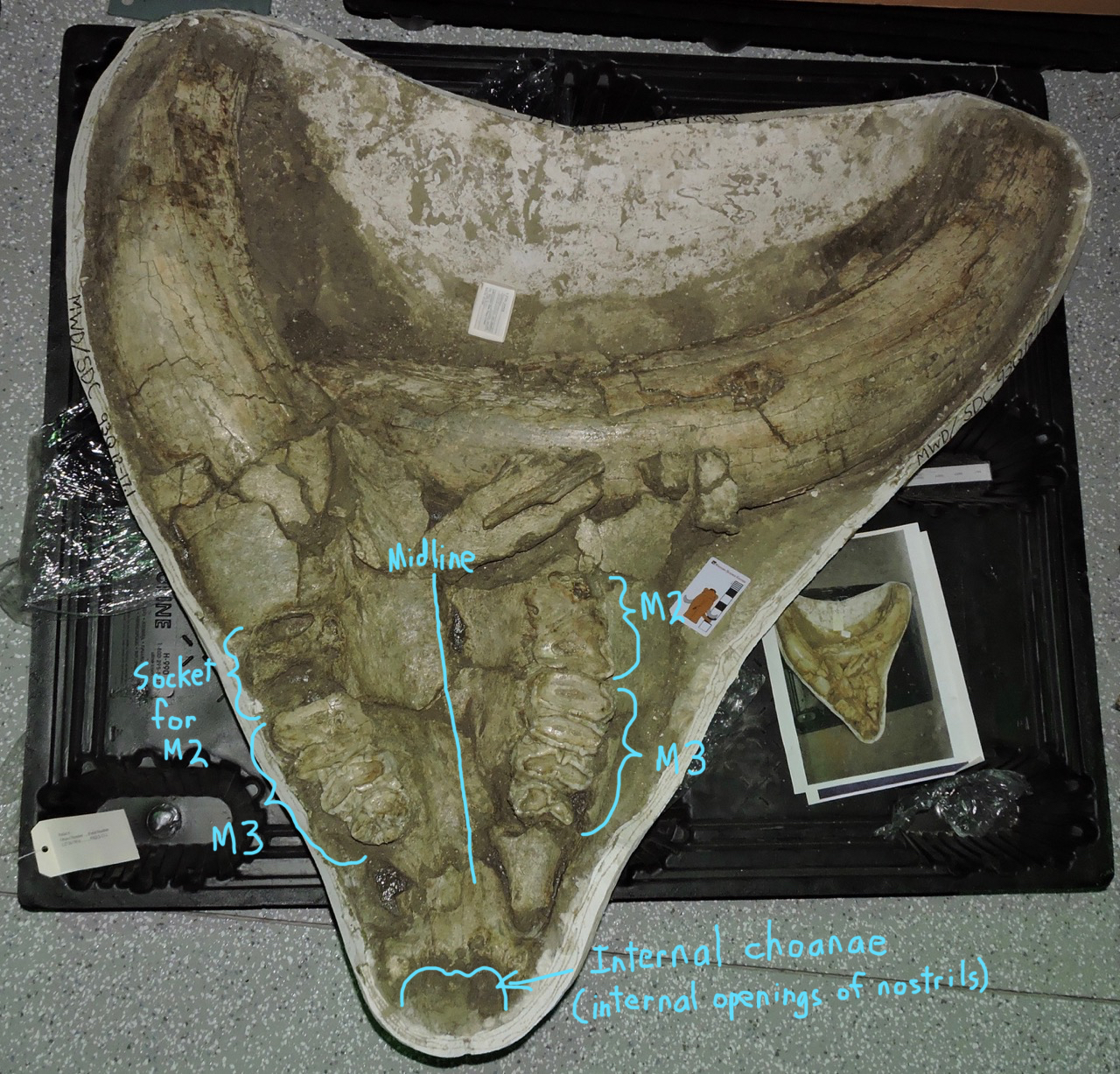

Our latest mastodon installment as we approach the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit opening 3 weeks from now is "Braces", a partial mastodon skull from the San Diego Canal."Braces" is still in his field jacket, with the ventral side exposed (and the large tusks do indicate that he's male). Below is an annotated version: "Braces" was a fully mature mastodon, roughly 40 years old based on tooth wear. The right 2nd molar is missing, and I'm pretty sure it had fallen out well before the mastodon died. It looks like the socket had started closing up, and the corresponding left second molar was worn all the way down to the bone.Braces' name comes from anomalies in the wear pattern on his teeth. Typically, proboscidean teeth wear in a fairly predictable way. The upper teeth wear more rapidly along the interior half of the occlusal surface (the lingual, or tongue-ward, side), while lower teeth wear more rapidly along the exterior half (the labial, or lip-ward, side). This may seem a little confusing, but it just means that when the upper and lower teeth occlude they do so along an angled surface, as shown in this schematic drawing of a cross-section through a mouth:

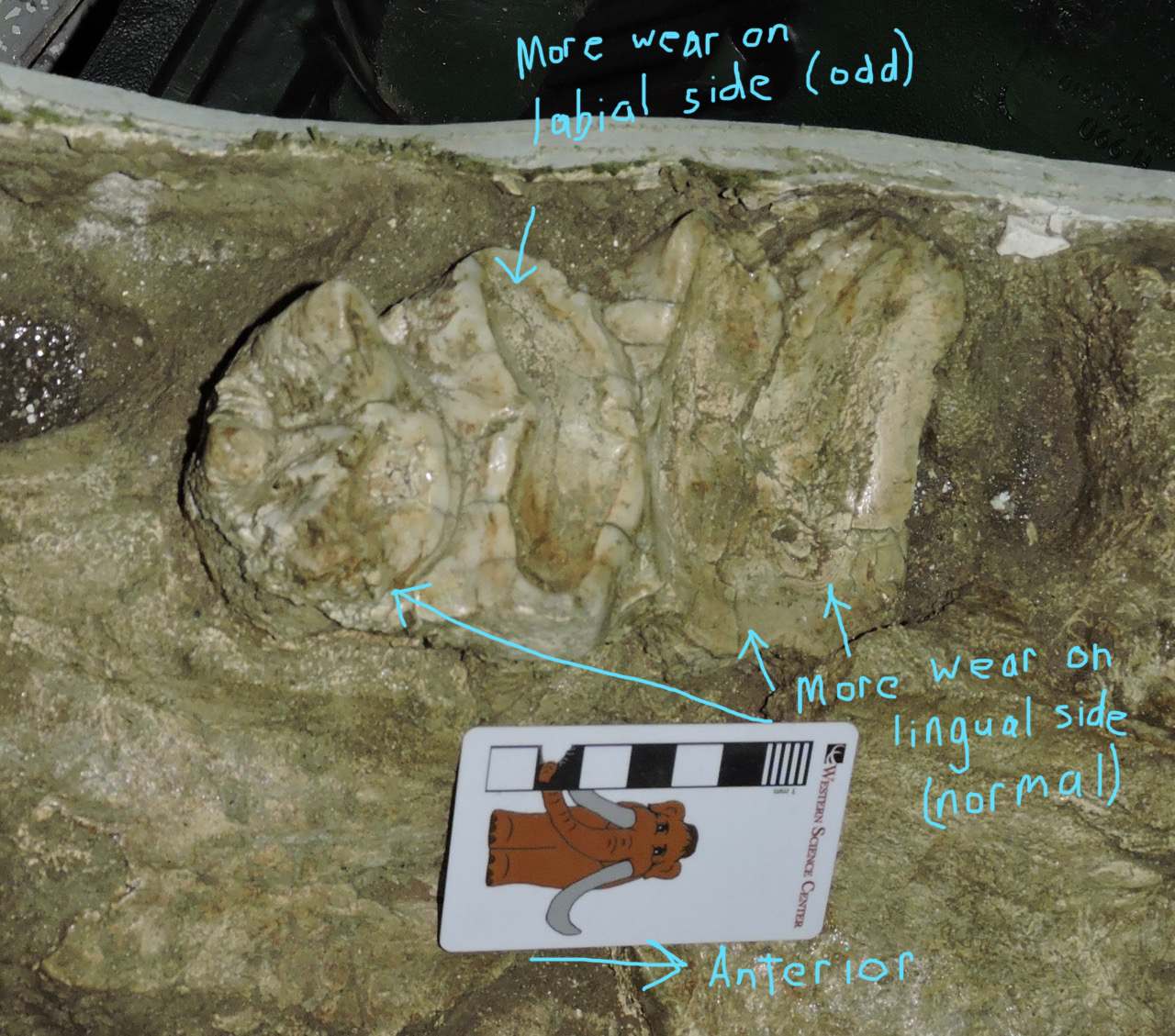

"Braces" was a fully mature mastodon, roughly 40 years old based on tooth wear. The right 2nd molar is missing, and I'm pretty sure it had fallen out well before the mastodon died. It looks like the socket had started closing up, and the corresponding left second molar was worn all the way down to the bone.Braces' name comes from anomalies in the wear pattern on his teeth. Typically, proboscidean teeth wear in a fairly predictable way. The upper teeth wear more rapidly along the interior half of the occlusal surface (the lingual, or tongue-ward, side), while lower teeth wear more rapidly along the exterior half (the labial, or lip-ward, side). This may seem a little confusing, but it just means that when the upper and lower teeth occlude they do so along an angled surface, as shown in this schematic drawing of a cross-section through a mouth:  Here's a closeup of Braces' right 3rd molar, followed by an annotated version:

Here's a closeup of Braces' right 3rd molar, followed by an annotated version:

In Braces, the upper 3rd molar starts off wearing just as it should, with much heavier wear on the lingual side. But then, on the third loph, the wear pattern reverses, with heavier wear on the labial side like you would expect to see in a lower tooth. Then, on the fourth loph, the wear switches back to the normal pattern with heavier wear on the lingual side.It seems that there was some anomaly with the way Braces' teeth were aligned and occluding with each other. I'm not sure what caused this. Unfortunately we don't have the lower jaw, which might help. Maybe he had an injury to his lower jaw that changed the way he closed his mouth? Certainly Max, who was a slightly younger animal, had several jaw injuries. Or maybe this has to do with the right 2nd molar being lost before the left on; perhaps that sets up an asymmetry in the chewing dynamics. If this is the case, it's possible that if Braces had lived longer the pattern would have reversed itself. Maybe this is a relatively common but temporary condition, that only occurs during the brief periods when the tooth count is different on each side of the jaw.Along with most of our other mastodons, Braces will be on display in our Valley of the Mastodons exhibit that opens on August 5.

In Braces, the upper 3rd molar starts off wearing just as it should, with much heavier wear on the lingual side. But then, on the third loph, the wear pattern reverses, with heavier wear on the labial side like you would expect to see in a lower tooth. Then, on the fourth loph, the wear switches back to the normal pattern with heavier wear on the lingual side.It seems that there was some anomaly with the way Braces' teeth were aligned and occluding with each other. I'm not sure what caused this. Unfortunately we don't have the lower jaw, which might help. Maybe he had an injury to his lower jaw that changed the way he closed his mouth? Certainly Max, who was a slightly younger animal, had several jaw injuries. Or maybe this has to do with the right 2nd molar being lost before the left on; perhaps that sets up an asymmetry in the chewing dynamics. If this is the case, it's possible that if Braces had lived longer the pattern would have reversed itself. Maybe this is a relatively common but temporary condition, that only occurs during the brief periods when the tooth count is different on each side of the jaw.Along with most of our other mastodons, Braces will be on display in our Valley of the Mastodons exhibit that opens on August 5.

Fossil Friday - mastodon calcaneum

Continuing with our mastodon spree in preparation for next month's "Valley of the Mastodons" workshop and exhibit, this week for Fossil Friday we have a mastodon calcaneum.This is a left calcaneum, seen above in posterior view. The calcaneum is the heel bone, and together with the astragalus makes up the ankle joint. In anterior view (actually anterior and slightly ventral, below) the two bright white surfaces are the articulations with the astragalus:

Continuing with our mastodon spree in preparation for next month's "Valley of the Mastodons" workshop and exhibit, this week for Fossil Friday we have a mastodon calcaneum.This is a left calcaneum, seen above in posterior view. The calcaneum is the heel bone, and together with the astragalus makes up the ankle joint. In anterior view (actually anterior and slightly ventral, below) the two bright white surfaces are the articulations with the astragalus: Here's a lateral view, with anterior to the left:

Here's a lateral view, with anterior to the left: The large mass of bone sticking off the top is called the tuber calcis. Humans are plantigrade animals, meaning that we walk with our feet on the ground. In our feet, the tuber calcis projects down and back, forming our heel. We actually walk on the bottom of the tuber calcis (covered with a thin layer of soft tissue), while various muscles attach to the top surface of the tuber calcis through the Achilles tendon. When these muscles flex the Achilles tendon pulls the tuber calcis up, rotating the foot down. When a ballerina stands en pointe, she is flexing these muscles and keeping the tuber calcis rotated up and forward.Most large mammals are not plantigrade but are instead digitigrade; they are en pointe all the time. However, different limb geometry means that they don't have to constantly flex a group of muscles to stay in that position. Instead, the foot between the ankle and toes acts like an additional leg segment, moving forward and backward at the ankle and held vertically when at rest. (Some people mistakenly believe that animals such as deer and horses have "backward knees"; they're actually looking at the ankle joint, not the knee.)Surprisingly, for all their bulk, proboscideans are digitigrade. Even though the toes are short and stout, the ankle is held high and the calcaneum is off the ground. (See these fantastic CT-based videos of elephant foot bones from What's in John's Freezer to see the relationships of the bones to each other.) When you look at an elephant's feet, it may not immediately be clear that they're digitigrade because there is a huge fatty pad that covers the palm and heel, turning the whole foot into a column. In the hind foot, the top back part of the fat pad is nestled under the calcaneum.Even with their thick, columnar legs, elephants have a fair range of mobility at the ankle, and can move their feet forward and back relative to the shin. This is consistent with the large tuber calcis, which remember serves as a muscle attachment point for pulling the foot back (in this case, pulling it back to the vertical, resting position). What is a bit surprising is that, compared to elephants and mammoths, the tuber calcis in mastodons is enormous, roughly twice as large. Perhaps foot strength and dexterity was more significant in mastodons for some reason?This calcaneum, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on display in the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit at the Western Science Center next month.

The large mass of bone sticking off the top is called the tuber calcis. Humans are plantigrade animals, meaning that we walk with our feet on the ground. In our feet, the tuber calcis projects down and back, forming our heel. We actually walk on the bottom of the tuber calcis (covered with a thin layer of soft tissue), while various muscles attach to the top surface of the tuber calcis through the Achilles tendon. When these muscles flex the Achilles tendon pulls the tuber calcis up, rotating the foot down. When a ballerina stands en pointe, she is flexing these muscles and keeping the tuber calcis rotated up and forward.Most large mammals are not plantigrade but are instead digitigrade; they are en pointe all the time. However, different limb geometry means that they don't have to constantly flex a group of muscles to stay in that position. Instead, the foot between the ankle and toes acts like an additional leg segment, moving forward and backward at the ankle and held vertically when at rest. (Some people mistakenly believe that animals such as deer and horses have "backward knees"; they're actually looking at the ankle joint, not the knee.)Surprisingly, for all their bulk, proboscideans are digitigrade. Even though the toes are short and stout, the ankle is held high and the calcaneum is off the ground. (See these fantastic CT-based videos of elephant foot bones from What's in John's Freezer to see the relationships of the bones to each other.) When you look at an elephant's feet, it may not immediately be clear that they're digitigrade because there is a huge fatty pad that covers the palm and heel, turning the whole foot into a column. In the hind foot, the top back part of the fat pad is nestled under the calcaneum.Even with their thick, columnar legs, elephants have a fair range of mobility at the ankle, and can move their feet forward and back relative to the shin. This is consistent with the large tuber calcis, which remember serves as a muscle attachment point for pulling the foot back (in this case, pulling it back to the vertical, resting position). What is a bit surprising is that, compared to elephants and mammoths, the tuber calcis in mastodons is enormous, roughly twice as large. Perhaps foot strength and dexterity was more significant in mastodons for some reason?This calcaneum, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on display in the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit at the Western Science Center next month.

Fossil Friday - mastodon axis vertebra

With the opening of the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit a little over a month away, we've started pulling specimens from the collections to work on layouts. The lab and collections workroom are full of mastodons!Today's specimen is a mastodon 2nd cervical (neck) vertebrae, more commonly referred to as the axis. It's shown above in anterior view, and below in posterior view:

With the opening of the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit a little over a month away, we've started pulling specimens from the collections to work on layouts. The lab and collections workroom are full of mastodons!Today's specimen is a mastodon 2nd cervical (neck) vertebrae, more commonly referred to as the axis. It's shown above in anterior view, and below in posterior view: Animals with large heads face real biomechanical hurdles. If you're a quadruped, your head is stuck out on the end of a neck and is otherwise unsupported. This puts tremendous stress on the neck vertebrae, and requires massive muscles to hold up the weight, which affects the entire skeleton. In proboscideans the problem is even worse, because they have a large, heavy brain and, right out in front where it causes the most stress, massively heavy teeth, tusks, and trunk. Proboscideans have addressed this issue in two ways: the skull itself is actually pretty lightly built for its size, and the neck vertebrae are compressed front to back so that the neck is relatively short. But even with a short neck, elephants sometimes need to move their heads. So while the neck vertebrae are short, they have massive attachment areas for muscles and some range of mobility between the vertebrae. The huge, robust neural arch and spine on this mastodon vertebra reflect the large muscles attached to it. Just as a "gee, whiz!" point, the mass of bone that forms the top of the neural canal is roughly the same size as the entire centrum of a bison cervical vertebra, and it's not as if bison have tiny heads!In most mammals, nodding the head up and down largely involves movement between the skull and the first cervical vertebra (the atlas). In contrast, if an animal rotates its head along a longitudinal axis, such as the RCA dog below (from Wikipedia), or the elephant in this video, much of the movement is occurring between the atlas and axis vertebrae.

Animals with large heads face real biomechanical hurdles. If you're a quadruped, your head is stuck out on the end of a neck and is otherwise unsupported. This puts tremendous stress on the neck vertebrae, and requires massive muscles to hold up the weight, which affects the entire skeleton. In proboscideans the problem is even worse, because they have a large, heavy brain and, right out in front where it causes the most stress, massively heavy teeth, tusks, and trunk. Proboscideans have addressed this issue in two ways: the skull itself is actually pretty lightly built for its size, and the neck vertebrae are compressed front to back so that the neck is relatively short. But even with a short neck, elephants sometimes need to move their heads. So while the neck vertebrae are short, they have massive attachment areas for muscles and some range of mobility between the vertebrae. The huge, robust neural arch and spine on this mastodon vertebra reflect the large muscles attached to it. Just as a "gee, whiz!" point, the mass of bone that forms the top of the neural canal is roughly the same size as the entire centrum of a bison cervical vertebra, and it's not as if bison have tiny heads!In most mammals, nodding the head up and down largely involves movement between the skull and the first cervical vertebra (the atlas). In contrast, if an animal rotates its head along a longitudinal axis, such as the RCA dog below (from Wikipedia), or the elephant in this video, much of the movement is occurring between the atlas and axis vertebrae. (OK, the pedant in me has to point out that, while nodding and rotating largely involve the atlas and axis respectively, the rest of the cervical vertebrae are also involved in these movements, so injury or fusion at any point in the neck will cause a decrease in mobility. In addition, humans, because our bipedal stance has resulted in precariously-balanced and misshapen heads, work a bit differently. From a vertebral standpoint, our equivalent motion to what the RCA dog is would be looking from left-to-right, but when we cock our head to the side, that's the vertebral equivalent to looking left-to-right in other mammals. Finally, the necks in non-mammal tetrapods such as reptiles and birds work quite differently from mammals, so much of this doesn't apply to them.)The mastodon axis shown here is actually part of an associated skeleton that came from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, which includes several other vertebrae, tusks, and a number of ribs. Like most of our mastodon material, it will be on exhibit starting in August.

(OK, the pedant in me has to point out that, while nodding and rotating largely involve the atlas and axis respectively, the rest of the cervical vertebrae are also involved in these movements, so injury or fusion at any point in the neck will cause a decrease in mobility. In addition, humans, because our bipedal stance has resulted in precariously-balanced and misshapen heads, work a bit differently. From a vertebral standpoint, our equivalent motion to what the RCA dog is would be looking from left-to-right, but when we cock our head to the side, that's the vertebral equivalent to looking left-to-right in other mammals. Finally, the necks in non-mammal tetrapods such as reptiles and birds work quite differently from mammals, so much of this doesn't apply to them.)The mastodon axis shown here is actually part of an associated skeleton that came from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, which includes several other vertebrae, tusks, and a number of ribs. Like most of our mastodon material, it will be on exhibit starting in August.

Fossil Friday - mastodon caudal vertebra

As promised, as we prepare for the Valley of the Mastodons workshop and exhibit, I'm going to be talking even more than usual about mastodons. We have hundreds of mastodon bones in the WSC collections, and we have to examine them all over the next month to decide what's going on exhibit (which will be most of them).The small bone shown above is a caudal (tail) vertebra, shown in dorsal view with anterior at the top. The ventral view is below:

As promised, as we prepare for the Valley of the Mastodons workshop and exhibit, I'm going to be talking even more than usual about mastodons. We have hundreds of mastodon bones in the WSC collections, and we have to examine them all over the next month to decide what's going on exhibit (which will be most of them).The small bone shown above is a caudal (tail) vertebra, shown in dorsal view with anterior at the top. The ventral view is below: Looking at elephant tails for comparison (there isn't a lot of literature on mastodon tails!) this vertebra appears to come from roughly the middle of the tail. Proboscidean tails are relatively limited in use (modern elephants will use them to brush off insects, babies will sometimes hold onto their mother's tail, etc.), so the more distal vertebrae are quite simple. This vertebra has a neural canal (the passage for the spinal cord) that is open dorsally and very small transverse processes, both typical for proboscidean caudal vertebrae.In anterior view (below) we can see that the vertebra is also missing the epiphysis that forms the end of the bone:

Looking at elephant tails for comparison (there isn't a lot of literature on mastodon tails!) this vertebra appears to come from roughly the middle of the tail. Proboscidean tails are relatively limited in use (modern elephants will use them to brush off insects, babies will sometimes hold onto their mother's tail, etc.), so the more distal vertebrae are quite simple. This vertebra has a neural canal (the passage for the spinal cord) that is open dorsally and very small transverse processes, both typical for proboscidean caudal vertebrae.In anterior view (below) we can see that the vertebra is also missing the epiphysis that forms the end of the bone: An unfused epiphysis is typically indicative of a bone that was still growing, suggesting that this was a relatively young animal. In fact, this vertebra is part of the associated skeleton of "Little Stevie", the most complete mastodon from Diamond Valley Lake. Based on his teeth and bone development, "Stevie" was a late adolescent, probably somewhere in the range of 18-22 years old.This vertebra, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on exhibit starting this August with the opening of Valley of the Mastodons.

An unfused epiphysis is typically indicative of a bone that was still growing, suggesting that this was a relatively young animal. In fact, this vertebra is part of the associated skeleton of "Little Stevie", the most complete mastodon from Diamond Valley Lake. Based on his teeth and bone development, "Stevie" was a late adolescent, probably somewhere in the range of 18-22 years old.This vertebra, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on exhibit starting this August with the opening of Valley of the Mastodons.

Fossil Friday - mastodon molar

This August we're opening a major new exhibit and hosting an associated workshop at Western Science Center, Valley of the Mastodons. In the lead-up to the exhibit/workshop, I'm going to be talking about mastodons even more than usual.The specimen shown above is a heavily-worn tooth in occlusal view. The anterior end of the tooth is at the top, and two corners are broken off. Based on the size, shape, and wear pattern, this appears to be an upper right 1st molar.Below is a lateral (labial) view, with anterior to the right:

This August we're opening a major new exhibit and hosting an associated workshop at Western Science Center, Valley of the Mastodons. In the lead-up to the exhibit/workshop, I'm going to be talking about mastodons even more than usual.The specimen shown above is a heavily-worn tooth in occlusal view. The anterior end of the tooth is at the top, and two corners are broken off. Based on the size, shape, and wear pattern, this appears to be an upper right 1st molar.Below is a lateral (labial) view, with anterior to the right: In this view it's clear that this tooth is almost completely worn away. The wear is heaviest at the anterior end, which is typical for proboscideans with horizontal tooth replacement. As this is an upper tooth, the wear is actually lighter on this side than on the medial (lingual) surface.This tooth was found along the San Diego Canal, apparently near the mastodon jaw we CT scanned a few weeks ago. However, it doesn't appear to be from the same animal, as that specimen had apparently lost its first molars some substantial amount of time prior to its death. This tooth, as well as nearly all of our other mastodon remains, will be on display this August in Valley of the Mastodons.

In this view it's clear that this tooth is almost completely worn away. The wear is heaviest at the anterior end, which is typical for proboscideans with horizontal tooth replacement. As this is an upper tooth, the wear is actually lighter on this side than on the medial (lingual) surface.This tooth was found along the San Diego Canal, apparently near the mastodon jaw we CT scanned a few weeks ago. However, it doesn't appear to be from the same animal, as that specimen had apparently lost its first molars some substantial amount of time prior to its death. This tooth, as well as nearly all of our other mastodon remains, will be on display this August in Valley of the Mastodons.

Fossil Friday - new mastodon CT scans

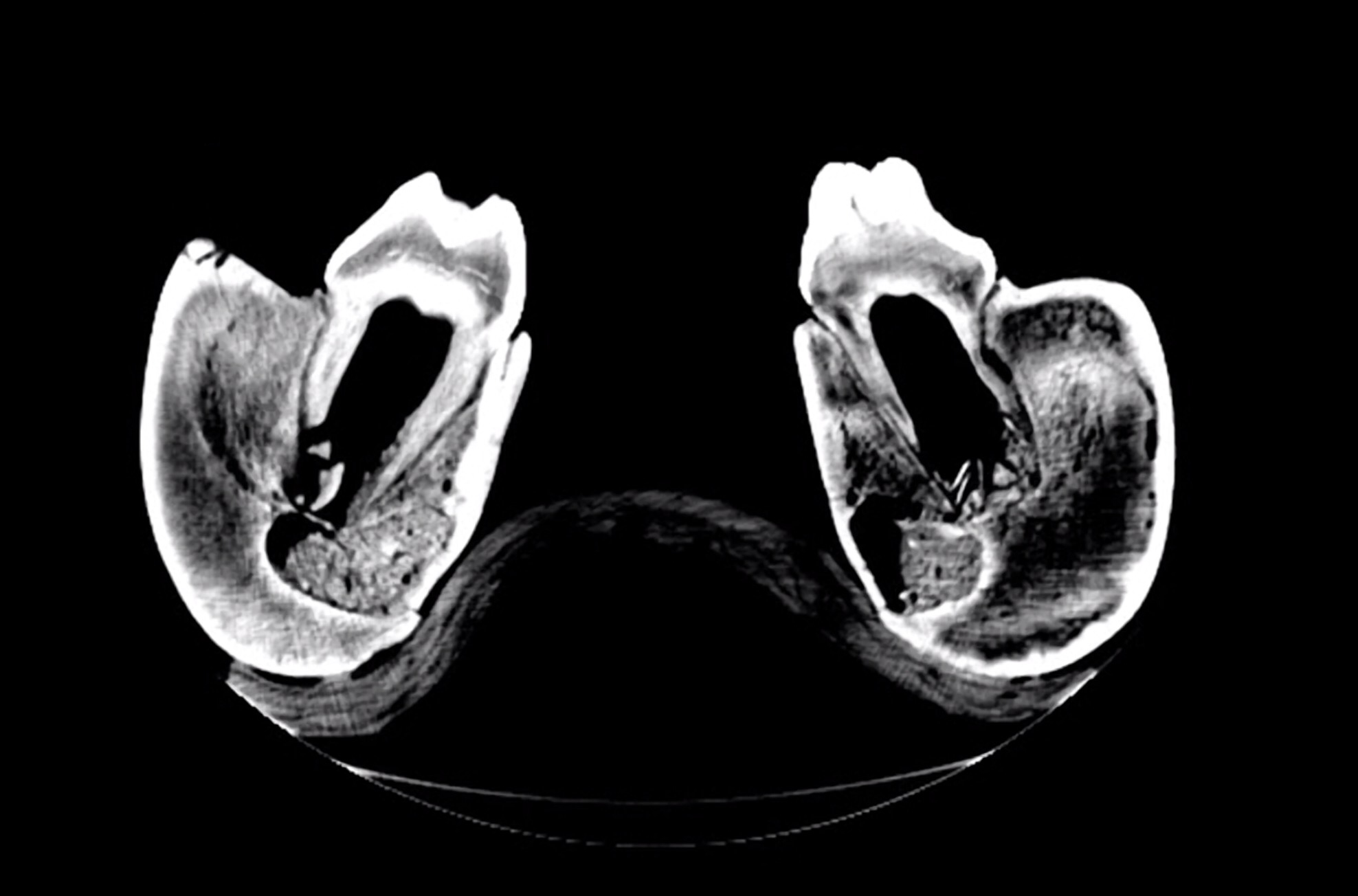

Almost two years ago we took Max's lower jaw to California Imaging and Diagnostics for a CT scan. We got some fascinating data that raised a lot of new questions, so to help answer them we recently took a second mastodon to CID for scanning.The particular specimen is from the San Diego Canal, and includes a nearly complete lower jaw and a partial cranium. The cranium was of particular interest to us. It was broken in such a way as to include the entire left tooth row including the tusk, but the fragment was narrow enough to fit through the medical CT scanner; a complete adult mastodon skull is typically far too large to fit through the scanner. Based on tooth wear, while this mastodon was an adult he (it appears to be a male) was as much as 10 years younger than Max, so it gives us an interesting point for comparison. We're still examining the data, so what I'm posting here is preliminary (I only examined most of the data myself for the first time yesterday):Here's a transverse section through the SDC specimen's lower jaw, cutting through the last roots on the 3rd molars:

Almost two years ago we took Max's lower jaw to California Imaging and Diagnostics for a CT scan. We got some fascinating data that raised a lot of new questions, so to help answer them we recently took a second mastodon to CID for scanning.The particular specimen is from the San Diego Canal, and includes a nearly complete lower jaw and a partial cranium. The cranium was of particular interest to us. It was broken in such a way as to include the entire left tooth row including the tusk, but the fragment was narrow enough to fit through the medical CT scanner; a complete adult mastodon skull is typically far too large to fit through the scanner. Based on tooth wear, while this mastodon was an adult he (it appears to be a male) was as much as 10 years younger than Max, so it gives us an interesting point for comparison. We're still examining the data, so what I'm posting here is preliminary (I only examined most of the data myself for the first time yesterday):Here's a transverse section through the SDC specimen's lower jaw, cutting through the last roots on the 3rd molars: For comparison here's a similar section through Max's jaw:

For comparison here's a similar section through Max's jaw: The SDC mastodon was a young animal, probably in his early 20's. His 3rd molars were still growing, and had large open pulp cavities and short roots. Max was a middle-aged mastodon in his mid-to-late 30's, with fully developed 3rd molars with deep roots and nearly closed pulp cavities.Here's a sagittal section through the SDC specimen's right dentary, followed by a similar section on Max:

The SDC mastodon was a young animal, probably in his early 20's. His 3rd molars were still growing, and had large open pulp cavities and short roots. Max was a middle-aged mastodon in his mid-to-late 30's, with fully developed 3rd molars with deep roots and nearly closed pulp cavities.Here's a sagittal section through the SDC specimen's right dentary, followed by a similar section on Max:

This view also emphasizes the huge open pulp cavity in the SDC specimen compared to Max's nearly solid teeth.Here's another sagittal section through the SDC right dentary, on a slightly different plane than the image above:

This view also emphasizes the huge open pulp cavity in the SDC specimen compared to Max's nearly solid teeth.Here's another sagittal section through the SDC right dentary, on a slightly different plane than the image above: Notice the differently-textured bone just in front of the 2nd molar, outlined in red below:

Notice the differently-textured bone just in front of the 2nd molar, outlined in red below: With their horizontal tooth replacement, proboscidean teeth are constantly moving forward in the jaw, which means the bone in the jaw is constantly being absorbed and redeposited. The SDC specimen had recently lost his first molar, and the socket is filled by young, spongy bone that shows up as a different texture in the scan. In the much older Max this part of the jaw is as dense as the surrounding bone.Below is a transverse section through the cranium, followed by a marked-up version. I've rotated the image so that it's approximately in life orientation (it was upside down in the scanner):

With their horizontal tooth replacement, proboscidean teeth are constantly moving forward in the jaw, which means the bone in the jaw is constantly being absorbed and redeposited. The SDC specimen had recently lost his first molar, and the socket is filled by young, spongy bone that shows up as a different texture in the scan. In the much older Max this part of the jaw is as dense as the surrounding bone.Below is a transverse section through the cranium, followed by a marked-up version. I've rotated the image so that it's approximately in life orientation (it was upside down in the scanner):

The blue area is the 3rd molar, at about the level of the 2nd lophid. The red area is actually the bottom of the unerupted part of the tusk, which extends all the way back at least to the 3rd molar. We can't tell in this specimen just how far back the tusk goes, because it's curving upward and the upper part of the cranium wasn't preserved.Finally, here's a section though a more distal part of the tusk:

The blue area is the 3rd molar, at about the level of the 2nd lophid. The red area is actually the bottom of the unerupted part of the tusk, which extends all the way back at least to the 3rd molar. We can't tell in this specimen just how far back the tusk goes, because it's curving upward and the upper part of the cranium wasn't preserved.Finally, here's a section though a more distal part of the tusk: Again, this is rotated into approximately life orientation. One side of the tusk is damaged, and splinters of the tusk have broken off the inside and are laying haphazardly in the pulp cavity (which also contains some sediment). The better-preserved area shows visible concentric lines, the tusk's growth rings.We'll be studying these new scans in detail over the summer and fall, so there will be more to come. Thanks to CID for providing access to their CT scanner and running these scans for us!

Again, this is rotated into approximately life orientation. One side of the tusk is damaged, and splinters of the tusk have broken off the inside and are laying haphazardly in the pulp cavity (which also contains some sediment). The better-preserved area shows visible concentric lines, the tusk's growth rings.We'll be studying these new scans in detail over the summer and fall, so there will be more to come. Thanks to CID for providing access to their CT scanner and running these scans for us!

Fossil Friday - proboscidean ulna

Over the last few weeks we've started pulling a lot of mastodon material from the collections (more on that in a future post). Some of the bones that are turning up are pretty interesting.The large bone fragment shown above is a small part of the proximal end of the right ulna, one of the bones in the forearm. It's shown above in lateral view, and below is looking at the proximal end (part of the articular surface for the elbow):