The popular image of dinosaurs is as indestructible monsters of old, but actually they were just as susceptible to injury and disease as any living animal. While working on part of a duck-billed hadrosaur in the WSC prep lab, volunteer Joe Reavis and I noticed something odd on one of the neural spines of this 79-million-year-old skeleton.

Fossil Friday - Osteoderms

Two weeks ago, Western Science Center's social media presented a large and rather complete 80-million-year-old turtle shell from the Menefee Formation in New Mexico. We've been making good progress on prepping that turtle and will have more to say about it soon. For today, I wanted to surprise you all with something that surprised us last week. WSC fossil prep volunteer Joe Reavis and I were sorting through bone fragments that will reattach to the turtle shell when we noticed a flat disk of bone that didn't seem to attach to anything else and with a surface showing a number of small pits (bottom row, second from right in the image). It was pretty clear that this was not part of the turtle, and that it was actually an osteoderm, a small bone that would have been set in the skin of some type of armored animal.

Fossil Friday - Ceratopsid Fossil Prep

Throughout 2019, I shared with you updates as Western Science Center fossil prep lab volunteer Joe Reavis worked on four large jackets that we collected at a single site in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico in 2018, along with our colleagues from Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. We knew these jackets contained various bones from a ceratopsid, one of the large, plant-eating, horned dinosaurs akin to Triceratops.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsid ilium

On May 17, I posted a photo of the ilium of a ceratopsid dinosaur that we collected in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. At the time, only the medial surface of the bone was visible; however, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working hard and has now prepped the lateral surface as well. On May 17, I identified the bone as a left ilium, but now that I can see the whole thing, I can say that it's actually a right ilium.This beautifully-preserved ilium is part of an incomplete skeleton that also includes vertebrae and ribs from the torso, as well as the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae to which this ilium would have attached. Ceratopsids, the great horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops, were very abundant and diverse in western North America during the Late Cretaceous; our specimen is around 79 million years old, and we can't yet determine what species it represents. This skeleton was collected in 2016-2018 by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

On May 17, I posted a photo of the ilium of a ceratopsid dinosaur that we collected in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. At the time, only the medial surface of the bone was visible; however, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working hard and has now prepped the lateral surface as well. On May 17, I identified the bone as a left ilium, but now that I can see the whole thing, I can say that it's actually a right ilium.This beautifully-preserved ilium is part of an incomplete skeleton that also includes vertebrae and ribs from the torso, as well as the sacrum, the series of fused vertebrae to which this ilium would have attached. Ceratopsids, the great horned dinosaurs such as Triceratops, were very abundant and diverse in western North America during the Late Cretaceous; our specimen is around 79 million years old, and we can't yet determine what species it represents. This skeleton was collected in 2016-2018 by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - ceratopsid illium

Last week for Fossil Friday, I posted the sacrum of a ceratopsid, a large horned dinosaur related to Triceratops. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hip bones attach. Today, I want to show you one of those hip bones from the same ceratopsid individual. This is the left ilium, showing the inner surface where it would have attached to the sacral ribs along a series of deep facets. At about 80 centimeters long, this ilium is not terribly big for a ceratopsid, but it still would have been a hefty animal, plodding around the forests and swamps of Late Cretaceous New Mexico.In the coming months, we will create 3D-printed replicas of the sacrum and ilium of this ceratopsid to see how they fit together, the first step in rebuilding this 79-million-year-old skeleton. We also have several vertebrae and ribs from the back. This specimen was collected during the 2017 and 2018 field seasons by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. The sacrum and ilium have both been prepped by WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Last week for Fossil Friday, I posted the sacrum of a ceratopsid, a large horned dinosaur related to Triceratops. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hip bones attach. Today, I want to show you one of those hip bones from the same ceratopsid individual. This is the left ilium, showing the inner surface where it would have attached to the sacral ribs along a series of deep facets. At about 80 centimeters long, this ilium is not terribly big for a ceratopsid, but it still would have been a hefty animal, plodding around the forests and swamps of Late Cretaceous New Mexico.In the coming months, we will create 3D-printed replicas of the sacrum and ilium of this ceratopsid to see how they fit together, the first step in rebuilding this 79-million-year-old skeleton. We also have several vertebrae and ribs from the back. This specimen was collected during the 2017 and 2018 field seasons by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. The sacrum and ilium have both been prepped by WSC lab volunteer Joe Reavis.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian sacrum

Horned dinosaurs were one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of western North America. Known as ceratopsids, these rhino- to elephant-sized beasts brandished horns, spikes, and frills on their massive skulls. More than 40 different species are known to have inhabited western North America at different points in time between 80 and 66 million years ago. The last of them was the great "three-horned face" - Triceratops.Ceratopsids have been known from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico since the 1990s, when paleontologists at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science reported fossils including a partial skeleton. More recent expeditions to the Menefee by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society have discovered further ceratopsid fossils, including another partial skeleton now being prepped at WSC.Today's image is the sacrum of that 79-million-year-old ceratopsid skeleton, recently prepped by WSC volunteer Joe Reavis. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hips were attached. In the image, the bottom surface of the bone is visible. We'll be working on more bones from this skeleton over the coming months, including a hip bone, more vertebrae, and ribs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Horned dinosaurs were one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of western North America. Known as ceratopsids, these rhino- to elephant-sized beasts brandished horns, spikes, and frills on their massive skulls. More than 40 different species are known to have inhabited western North America at different points in time between 80 and 66 million years ago. The last of them was the great "three-horned face" - Triceratops.Ceratopsids have been known from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico since the 1990s, when paleontologists at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science reported fossils including a partial skeleton. More recent expeditions to the Menefee by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society have discovered further ceratopsid fossils, including another partial skeleton now being prepped at WSC.Today's image is the sacrum of that 79-million-year-old ceratopsid skeleton, recently prepped by WSC volunteer Joe Reavis. The sacrum is a series of fused vertebrae to which the hips were attached. In the image, the bottom surface of the bone is visible. We'll be working on more bones from this skeleton over the coming months, including a hip bone, more vertebrae, and ribs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Mistaken Identity

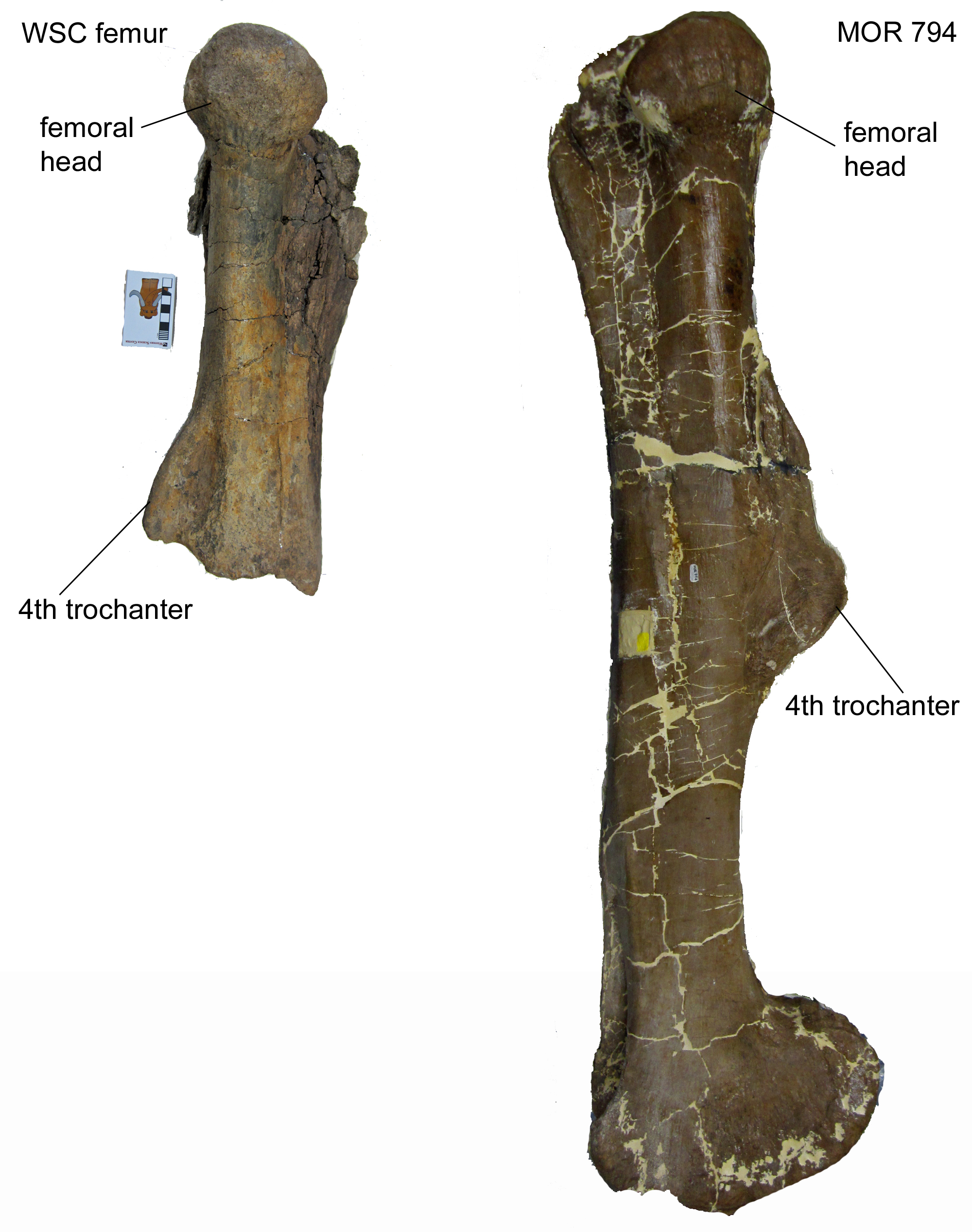

On March 8 Fossil Friday, I posted an 80-million-year-old dinosaur bone from New Mexico, which I identified as a tibia (shin bone). At the time, it was only partially prepped, and since then, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working tirelessly to remove the remaining mudstone.It turns out the "tibia" is actually a femur! It's the proximal half of the left femur of a hadrosaur, one of the large duck-billed plant-eating dinosaurs that are so abundant in Upper Cretaceous rocks throughout the American West. Comparison with a complete hadrosaur femur from Montana (Museum of the Rockies specimen MOR 794) allows us to identify several major features, including the head that fitted into the hip socket and the 4th trochanter, a major muscle attachment site. It also shows that the WSC femur is from a fairly large individual, probably close to 30 feet long.Hadrosaur bones are very common in the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which this femur was collected by my colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We'll have more to say in the near future.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

On March 8 Fossil Friday, I posted an 80-million-year-old dinosaur bone from New Mexico, which I identified as a tibia (shin bone). At the time, it was only partially prepped, and since then, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis has been working tirelessly to remove the remaining mudstone.It turns out the "tibia" is actually a femur! It's the proximal half of the left femur of a hadrosaur, one of the large duck-billed plant-eating dinosaurs that are so abundant in Upper Cretaceous rocks throughout the American West. Comparison with a complete hadrosaur femur from Montana (Museum of the Rockies specimen MOR 794) allows us to identify several major features, including the head that fitted into the hip socket and the 4th trochanter, a major muscle attachment site. It also shows that the WSC femur is from a fairly large individual, probably close to 30 feet long.Hadrosaur bones are very common in the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which this femur was collected by my colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We'll have more to say in the near future.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - dinosaur tibia

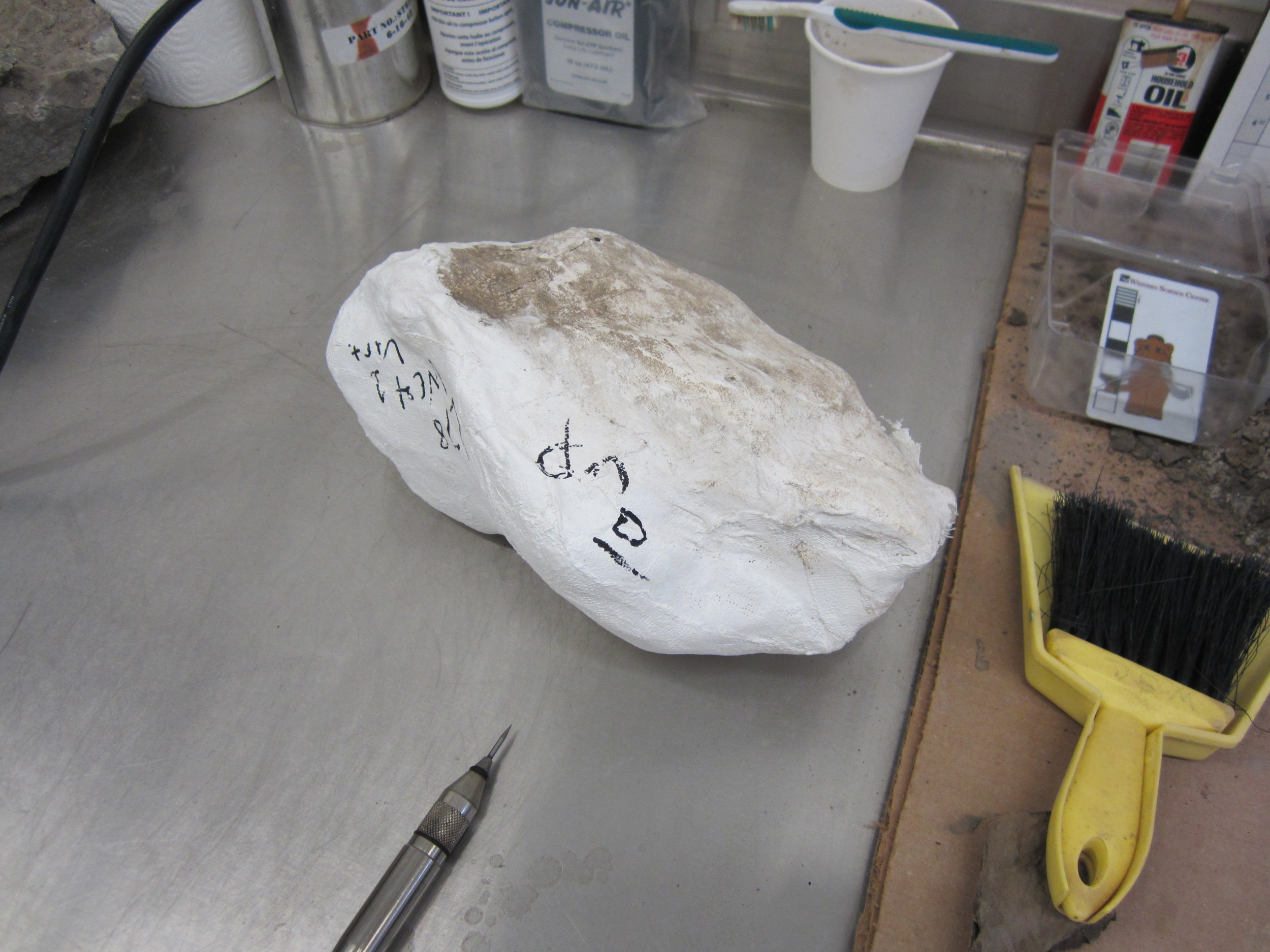

We have discovered many isolated dinosaur limb bones in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. Although it's difficult to infer the full appearance of a dinosaur from a single bone, even isolated bones can tell us a great deal about what kinds of dinosaurs were roaming around 80 million years ago, and can be very surprising!This bone was collected by my colleagues at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and volunteers with the Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We have been thinking that it was possibly two dinosaur limb bones next to each other. However, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis opened up the plaster jacket this week, and it turns out that it contains a single massive shin bone, a tibia. The bone is still partially encased in mudstone, but we'll keep working on it to determine what sort of dinosaur walked around on this immensely thick bone.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

We have discovered many isolated dinosaur limb bones in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. Although it's difficult to infer the full appearance of a dinosaur from a single bone, even isolated bones can tell us a great deal about what kinds of dinosaurs were roaming around 80 million years ago, and can be very surprising!This bone was collected by my colleagues at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and volunteers with the Southwest Paleontological Society in 2015. We have been thinking that it was possibly two dinosaur limb bones next to each other. However, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis opened up the plaster jacket this week, and it turns out that it contains a single massive shin bone, a tibia. The bone is still partially encased in mudstone, but we'll keep working on it to determine what sort of dinosaur walked around on this immensely thick bone.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - dinosaur limb bone

In the Western Science Center lab, we're making steady progress through several field seasons' worth of fossils from the Menefee Formation in New Mexico. We're working on fossils of dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and plants, all dating to around 80 million years ago.This week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began prepping a fairly hefty dinosaur limb bone that was collected in 2016 by me and colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. We're not yet certain what type of dinosaur this is from, or even which bone in the skeleton this is. One of the ends of the bone had eroded out onto the hillside prior to discovery, so we need to see if we can piece it back together and reattach it to the rest of the bone. There's always more to learn!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

In the Western Science Center lab, we're making steady progress through several field seasons' worth of fossils from the Menefee Formation in New Mexico. We're working on fossils of dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and plants, all dating to around 80 million years ago.This week, WSC volunteer Joe Reavis began prepping a fairly hefty dinosaur limb bone that was collected in 2016 by me and colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. We're not yet certain what type of dinosaur this is from, or even which bone in the skeleton this is. One of the ends of the bone had eroded out onto the hillside prior to discovery, so we need to see if we can piece it back together and reattach it to the rest of the bone. There's always more to learn!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian vertebra

On January 25, I showed you a horned dinosaur vertebra that was still partially encased in its plaster field jacket. Western Science Center volunteer John Deleon has been working hard on this vertebra for the last several weeks and has made great progress. The vertebra is now completely freed from its jacket, and is awaiting a bit more matrix removal and gluing before it is finished.This vertebra is part of a partial ceratopsian skeleton excavated in New Mexico in 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. At between 80 and 79 million years old, this skeleton is among the oldest specimens of large horned dinosaurs from North America. We are not yet certain what kind of horned dinosaur this is, but there are numerous more bones from the same animal waiting to be prepared in the WSC lab.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

On January 25, I showed you a horned dinosaur vertebra that was still partially encased in its plaster field jacket. Western Science Center volunteer John Deleon has been working hard on this vertebra for the last several weeks and has made great progress. The vertebra is now completely freed from its jacket, and is awaiting a bit more matrix removal and gluing before it is finished.This vertebra is part of a partial ceratopsian skeleton excavated in New Mexico in 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. At between 80 and 79 million years old, this skeleton is among the oldest specimens of large horned dinosaurs from North America. We are not yet certain what kind of horned dinosaur this is, but there are numerous more bones from the same animal waiting to be prepared in the WSC lab.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian vertebra

Identifying fossil bones can be quite the challenge. Fossils might be broken, scattered, or distorted from the weight of the rock encasing them. This dinosaur bone was collected in June 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. We know from other bones collected in the same spot that we are dealing with the 79-million-year-old partial skeleton of a ceratopsid, one of the large horned dinosaurs related to Triceratops.In the field, all we could see was a flat but somewhat intricate surface that we thought might be a skull bone. WSC volunteer John Deleon recently started prepping this fossil out of its small plaster jacket, so we can see more of its shape and features for the first time. Turns out this bone is actually a highly distorted vertebra that has been flattened side to side. Right now it is visible only from the left side. Many characteristics of a typical vertebra are observable, including the centrum (the main body of the vertebra), the neural spine, and the left prezygapophysis and postzygapophysis (along with the centrum, these structures are where the vertebra would articulate with the vertebra in front of it and the one behind it).We have many more vertebrae, ribs, and a large hip bone to prepare from this ceratopsid, so we will have much more to say about this dinosaur in the near future.

Identifying fossil bones can be quite the challenge. Fossils might be broken, scattered, or distorted from the weight of the rock encasing them. This dinosaur bone was collected in June 2018 by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. We know from other bones collected in the same spot that we are dealing with the 79-million-year-old partial skeleton of a ceratopsid, one of the large horned dinosaurs related to Triceratops.In the field, all we could see was a flat but somewhat intricate surface that we thought might be a skull bone. WSC volunteer John Deleon recently started prepping this fossil out of its small plaster jacket, so we can see more of its shape and features for the first time. Turns out this bone is actually a highly distorted vertebra that has been flattened side to side. Right now it is visible only from the left side. Many characteristics of a typical vertebra are observable, including the centrum (the main body of the vertebra), the neural spine, and the left prezygapophysis and postzygapophysis (along with the centrum, these structures are where the vertebra would articulate with the vertebra in front of it and the one behind it).We have many more vertebrae, ribs, and a large hip bone to prepare from this ceratopsid, so we will have much more to say about this dinosaur in the near future.

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur metatarsal

Discovering a dinosaur skeleton is a rare and special event.Most often, when out exploring in the badlands of New Mexico, we find isolated bones. However, even an isolated bone offers a wealth of information, about what kinds of animals were living in the area 79 million years ago, the depositional environment, and any unusual anatomical features or pathologies. Every summer, we collect numerous isolated bones of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and other animals from the Menefee Formation.Western Science Center prep lab volunteer John Deleon recently began preparing this dinosaur bone, which was collected by Southwest Paleontological Society volunteers Ben Mohler and Jake Kudlinski during our expedition last June. No other bones were found nearby, but this bone itself is well preserved and certainly worthy of the effort and study. It is a metatarsal, one of the large foot bones situated between the ankle and the toes, and probably belonged to a duck-billed plant-eating hadrosaur. Isolated hadrosaur bones, mostly limb bones and vertebrae, are the most commonly found dinosaur fossils in the Menefee Formation, suggesting that hadrosaurs probably were quite abundant in the ancient ecosystem. We'll be able to compare this bone to other limb bones we have collected over the years.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Discovering a dinosaur skeleton is a rare and special event.Most often, when out exploring in the badlands of New Mexico, we find isolated bones. However, even an isolated bone offers a wealth of information, about what kinds of animals were living in the area 79 million years ago, the depositional environment, and any unusual anatomical features or pathologies. Every summer, we collect numerous isolated bones of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and other animals from the Menefee Formation.Western Science Center prep lab volunteer John Deleon recently began preparing this dinosaur bone, which was collected by Southwest Paleontological Society volunteers Ben Mohler and Jake Kudlinski during our expedition last June. No other bones were found nearby, but this bone itself is well preserved and certainly worthy of the effort and study. It is a metatarsal, one of the large foot bones situated between the ankle and the toes, and probably belonged to a duck-billed plant-eating hadrosaur. Isolated hadrosaur bones, mostly limb bones and vertebrae, are the most commonly found dinosaur fossils in the Menefee Formation, suggesting that hadrosaurs probably were quite abundant in the ancient ecosystem. We'll be able to compare this bone to other limb bones we have collected over the years.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - dinosaur jacket

The fossil prep lab at Western Science Center is abuzz these days (literally, when the air scribes are blasting away). WSC staff and volunteers are working their way through the half-ton of fossils we brought back to the museum last summer from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.Much of our recent prep effort has focused on the hadrosaur skeleton I posted about back in September and October. We're now moving on to some of the smaller items we brought back.One of the new sites we documented and collected during the 2018 field season is a scatter of at least half a dozen dinosaur bones, discovered by WSC volunteer John DeLeon. Although the bones are highly weathered, we collected them all and got them safely back to the museum. Given their close association at the field site and the absence of any other fossil organisms, these bones probably all belong to the same individual dinosaur. John opened up the largest plaster jacket from the site yesterday. There is a little knob of bone exposed to the left in the image; the rest of the bone is underneath the fossilized tree branch to the right. We don't know what type of dinosaur is represented by these bones, but hopefully the answer will emerge as John continues his work.This specimen and all the Menefee fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

The fossil prep lab at Western Science Center is abuzz these days (literally, when the air scribes are blasting away). WSC staff and volunteers are working their way through the half-ton of fossils we brought back to the museum last summer from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.Much of our recent prep effort has focused on the hadrosaur skeleton I posted about back in September and October. We're now moving on to some of the smaller items we brought back.One of the new sites we documented and collected during the 2018 field season is a scatter of at least half a dozen dinosaur bones, discovered by WSC volunteer John DeLeon. Although the bones are highly weathered, we collected them all and got them safely back to the museum. Given their close association at the field site and the absence of any other fossil organisms, these bones probably all belong to the same individual dinosaur. John opened up the largest plaster jacket from the site yesterday. There is a little knob of bone exposed to the left in the image; the rest of the bone is underneath the fossilized tree branch to the right. We don't know what type of dinosaur is represented by these bones, but hopefully the answer will emerge as John continues his work.This specimen and all the Menefee fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - juvenile hadrosaur jaw

Last week, five staff members from the Western Science Center, including yours truly, traveled to Albuquerque to attend the 2018 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference. We presented six posters on the research, outreach, and educational activities taking place at the museum. Three of the posters dealt with fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, including the new dinosaurs Invictarx (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/08/24/fossil-friday-invictarx-zephyri/) and Dynamoterror (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/10/12/fossil-friday-dynamoterror-dynastes/). We presented this research with our colleagues from Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society.This beautiful little bone was the subject of a poster led by Kara Kelley, who has been participating in Menefee expeditions since 2012 and is now an undergraduate at the University of Arizona - Tucson. It's the left maxilla (upper jaw bone) from a very young, very small hadrosaur, which Kara discovered in 2016. Bones of baby dinosaurs are often rare, and this remains the only such bone we have collected in the Menefee Formation so far. In the image, the outer surface of the bone is shown, with a row of tiny teeth along the bottom. The animal's snout would be towards the left of the image, and the back of the skull towards the right. We can't yet tell exactly what kind of hadrosaur this little maxilla belongs to, but it does provide information on the anatomy of a young hadrosaur that lived 80 million years ago.And lest you think that we have two tiny hadrosaur maxillae, the bottom one is actually a painted 3D-print that we created here at Western Science Center through photogrammetry. Now we have a replica of the maxilla that we can take to events and conferences to show people and highlight just one of the many research projects unfolding here at the museum.Andrew McDonald

Last week, five staff members from the Western Science Center, including yours truly, traveled to Albuquerque to attend the 2018 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference. We presented six posters on the research, outreach, and educational activities taking place at the museum. Three of the posters dealt with fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, including the new dinosaurs Invictarx (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/08/24/fossil-friday-invictarx-zephyri/) and Dynamoterror (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/10/12/fossil-friday-dynamoterror-dynastes/). We presented this research with our colleagues from Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society.This beautiful little bone was the subject of a poster led by Kara Kelley, who has been participating in Menefee expeditions since 2012 and is now an undergraduate at the University of Arizona - Tucson. It's the left maxilla (upper jaw bone) from a very young, very small hadrosaur, which Kara discovered in 2016. Bones of baby dinosaurs are often rare, and this remains the only such bone we have collected in the Menefee Formation so far. In the image, the outer surface of the bone is shown, with a row of tiny teeth along the bottom. The animal's snout would be towards the left of the image, and the back of the skull towards the right. We can't yet tell exactly what kind of hadrosaur this little maxilla belongs to, but it does provide information on the anatomy of a young hadrosaur that lived 80 million years ago.And lest you think that we have two tiny hadrosaur maxillae, the bottom one is actually a painted 3D-print that we created here at Western Science Center through photogrammetry. Now we have a replica of the maxilla that we can take to events and conferences to show people and highlight just one of the many research projects unfolding here at the museum.Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Dynamoterror dynastes

Welcome Dynamoterror dynastes! This is another very special Fossil Friday for Western Science Center and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. Hot on the heels of our new armored herbivorous dinosaur, Invictarx zephyri comes this new tyrannosaur. Like Invictarx, Dynamoterror lived 80 million years ago in what is now New Mexico and is published in the online open-access journal PeerJ. Dynamoterror is known from an incomplete skeleton that includes bones from the skull, hand, foot, and many other fragments.

This is another very special Fossil Friday for Western Science Center and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. Hot on the heels of our new armored herbivorous dinosaur, Invictarx zephyri comes this new tyrannosaur. Like Invictarx, Dynamoterror lived 80 million years ago in what is now New Mexico and is published in the online open-access journal PeerJ. Dynamoterror is known from an incomplete skeleton that includes bones from the skull, hand, foot, and many other fragments. The first image shows the two frontal bones from the top of the skull of Dynamoterror (left and right) and the 3D-print of the composite frontals created at Western Science Center (center). We made the 3D-print by laser-scanning the actual fossils, building 3D digital models of them, and then mirroring and combining the models based upon overlapping anatomical features preserved on both frontals. This 3D-print helped us refine our interpretation of the anatomy in this region of the skull and is a nifty item to share at public events!Dynamoterror lived at the same time and place as Invictarx and the hadrosaur I have posted for Fossil Friday the last three weeks, and probably was quite a threat to them. Paleoartist Brian Engh has depicted a less than friendly encounter between Dynamoterror and Invictarx in a spectacular piece of artwork.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

The first image shows the two frontal bones from the top of the skull of Dynamoterror (left and right) and the 3D-print of the composite frontals created at Western Science Center (center). We made the 3D-print by laser-scanning the actual fossils, building 3D digital models of them, and then mirroring and combining the models based upon overlapping anatomical features preserved on both frontals. This 3D-print helped us refine our interpretation of the anatomy in this region of the skull and is a nifty item to share at public events!Dynamoterror lived at the same time and place as Invictarx and the hadrosaur I have posted for Fossil Friday the last three weeks, and probably was quite a threat to them. Paleoartist Brian Engh has depicted a less than friendly encounter between Dynamoterror and Invictarx in a spectacular piece of artwork.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur update #2

For the last two weeks, I've been giving you updates on the preparation of a big block of rock packed full of hadrosaur bones from New Mexico.All seven bones have now been freed and Western Science Center staff and volunteers are putting the finishing touches on them - removing the last bits of rock, repairing breaks, and reinforcing cracks.

For the last two weeks, I've been giving you updates on the preparation of a big block of rock packed full of hadrosaur bones from New Mexico.All seven bones have now been freed and Western Science Center staff and volunteers are putting the finishing touches on them - removing the last bits of rock, repairing breaks, and reinforcing cracks. Volunteer Joe Reavis, who worked extremely diligently on the big block for over a month, is now moving on to some smaller jackets from the same quarry, starting with the small jacket pictured here. There are two more jackets twice the size of this one! What parts of this 80-million-year-old herbivorous dinosaur do they contain? I'll continue to post updates as more of this remarkable animal is freed from the mudstone. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Volunteer Joe Reavis, who worked extremely diligently on the big block for over a month, is now moving on to some smaller jackets from the same quarry, starting with the small jacket pictured here. There are two more jackets twice the size of this one! What parts of this 80-million-year-old herbivorous dinosaur do they contain? I'll continue to post updates as more of this remarkable animal is freed from the mudstone. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur jacket update

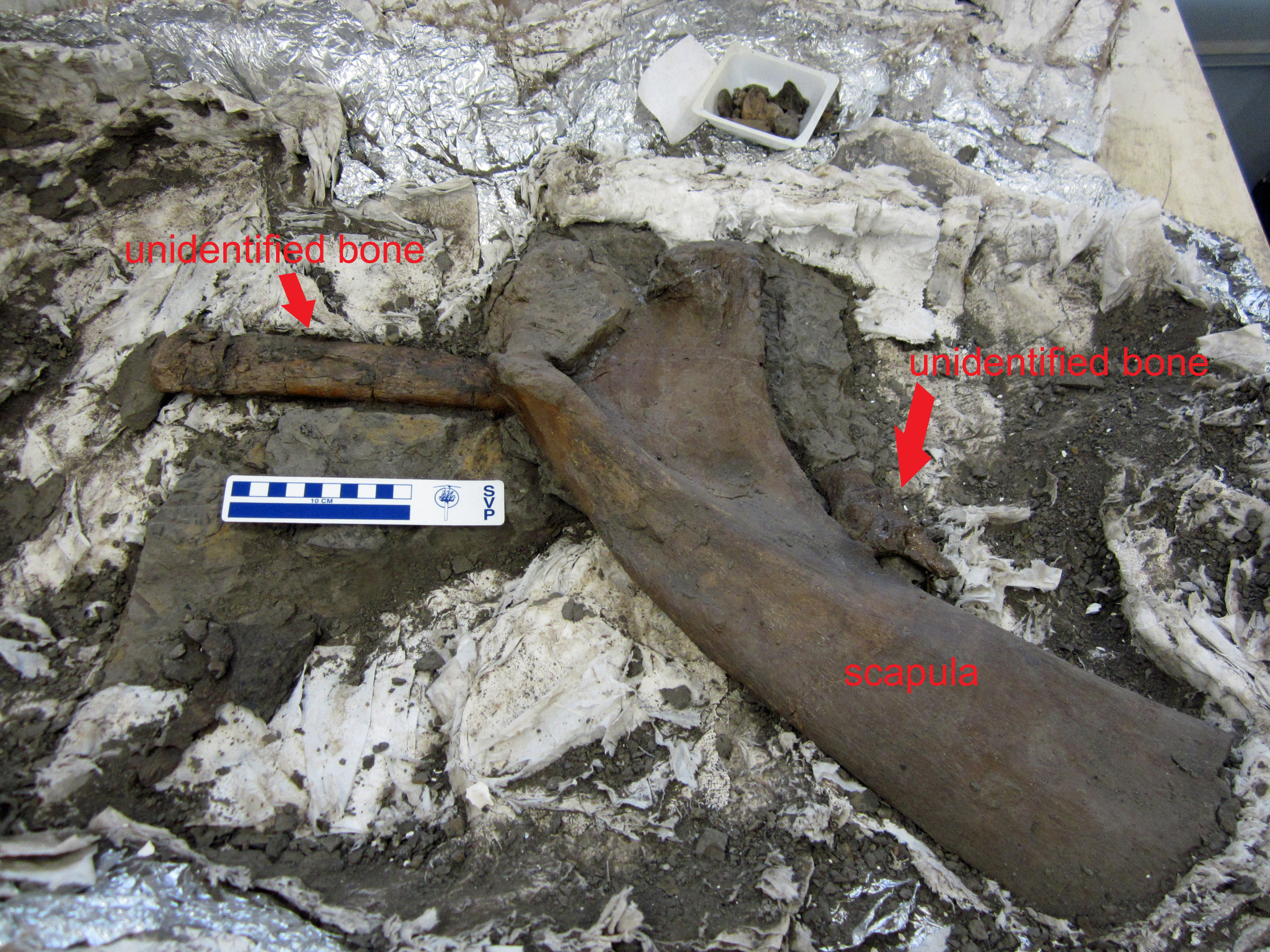

Last week for Fossil Friday, we posted about a big plaster jacket packed full of 80-million-year-old hadrosaur bones, which we brought back to the Western Science Center from New Mexico in June.Volunteer Joe Reavis has been working very diligently on removing the rock from the large but quite fragile bones. Every week brings more progress and greater understanding of which parts of the animal are actually present.Since last Friday, Joe has separated the two forearm bones from the scapula. It was all hands on deck earlier this week as we carefully lifted the two forearm bones away from the jacket, leaving the scapula completely intact. Last week, I identified the two long forearm bones as the left and right radii (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/fossil-friday-hadrosaur-bones/#more-1697). However, one of them is not a radius after all, but is instead an ulna, the other long bone in the forearm.

Last week for Fossil Friday, we posted about a big plaster jacket packed full of 80-million-year-old hadrosaur bones, which we brought back to the Western Science Center from New Mexico in June.Volunteer Joe Reavis has been working very diligently on removing the rock from the large but quite fragile bones. Every week brings more progress and greater understanding of which parts of the animal are actually present.Since last Friday, Joe has separated the two forearm bones from the scapula. It was all hands on deck earlier this week as we carefully lifted the two forearm bones away from the jacket, leaving the scapula completely intact. Last week, I identified the two long forearm bones as the left and right radii (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/fossil-friday-hadrosaur-bones/#more-1697). However, one of them is not a radius after all, but is instead an ulna, the other long bone in the forearm. Finding fossils in the field is not the end-all and be-all of discovery. Instead, it's only the first step. As we continue to clean the bones of this hadrosaur skeleton, we will refine the identities of the preserved bones and eventually start to investigate what kind of hadrosaur we have sitting in our lab.

Finding fossils in the field is not the end-all and be-all of discovery. Instead, it's only the first step. As we continue to clean the bones of this hadrosaur skeleton, we will refine the identities of the preserved bones and eventually start to investigate what kind of hadrosaur we have sitting in our lab. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald.

Fossil Friday - hadrosaur bones

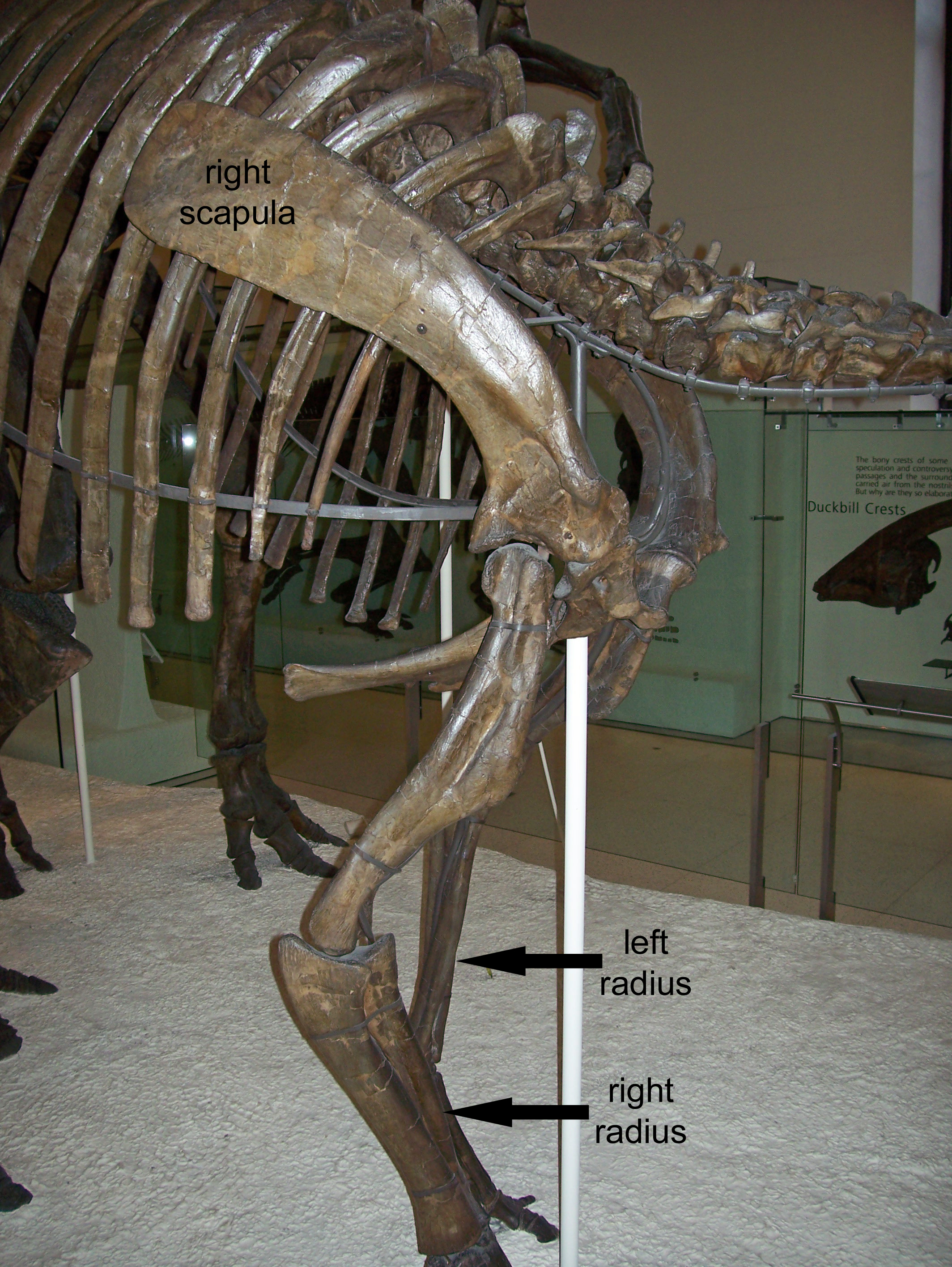

Being wrong is part of the scientific process. Scientists make new discoveries every day, and sometimes prior ideas are supported and sometimes they are refuted as we learn more.Today's Fossil Friday is a perfect example of this, as well as being a really exciting fossil! In June, my colleagues and I returned to the Western Science Center after three weeks of field work in New Mexico. Among the half-ton of 80-million-year-old fossils we brought back was a large plaster jacket containing what I had identified as several bones of a theropod, some sort of medium-sized meat-eating dinosaur.For the last month, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis has been preparing this big block of rock, carefully revealing the bones within. His work has led to a bit of a surprise - the bones are not those of a meat-eating theropod, but instead a plant-eating hadrosaur! Hadrosaurs are often nick-named the "duck-billed" dinosaurs, because of the wide beaks at the front of their mouths. These herbivores could reach 30 feet or more in length and were extremely common in North America during the last 20 million years of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction 66 million years ago that wiped out all the dinosaurs except modern birds.Isolated hadrosaur bones are abundant in the Menefee Formation, the layer of rock we are studying in New Mexico. However, this large jacket contains at least three limb bones in close proximity. So far, Joe has uncovered the right scapula (shoulder blade) and both radii (the radius is a long bone in the forearm). This next image shows the arms of AMNH 5886, a skeleton of the later hadrosaur Edmontosaurus annectens, which I photographed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The right scapula and both the left radius and right radius are labelled.

Being wrong is part of the scientific process. Scientists make new discoveries every day, and sometimes prior ideas are supported and sometimes they are refuted as we learn more.Today's Fossil Friday is a perfect example of this, as well as being a really exciting fossil! In June, my colleagues and I returned to the Western Science Center after three weeks of field work in New Mexico. Among the half-ton of 80-million-year-old fossils we brought back was a large plaster jacket containing what I had identified as several bones of a theropod, some sort of medium-sized meat-eating dinosaur.For the last month, Western Science Center volunteer Joe Reavis has been preparing this big block of rock, carefully revealing the bones within. His work has led to a bit of a surprise - the bones are not those of a meat-eating theropod, but instead a plant-eating hadrosaur! Hadrosaurs are often nick-named the "duck-billed" dinosaurs, because of the wide beaks at the front of their mouths. These herbivores could reach 30 feet or more in length and were extremely common in North America during the last 20 million years of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction 66 million years ago that wiped out all the dinosaurs except modern birds.Isolated hadrosaur bones are abundant in the Menefee Formation, the layer of rock we are studying in New Mexico. However, this large jacket contains at least three limb bones in close proximity. So far, Joe has uncovered the right scapula (shoulder blade) and both radii (the radius is a long bone in the forearm). This next image shows the arms of AMNH 5886, a skeleton of the later hadrosaur Edmontosaurus annectens, which I photographed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The right scapula and both the left radius and right radius are labelled. There is still more rock to be removed in the big jacket, and we brought back half a dozen smaller jackets containing other bones from the same site, one of which contains a hadrosaur vertebra. So, we will have much more to say about this remarkable animal in the future. The fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

There is still more rock to be removed in the big jacket, and we brought back half a dozen smaller jackets containing other bones from the same site, one of which contains a hadrosaur vertebra. So, we will have much more to say about this remarkable animal in the future. The fossils were collected by staff and volunteers from the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald

Fossil Friday - Invictarx zephyri

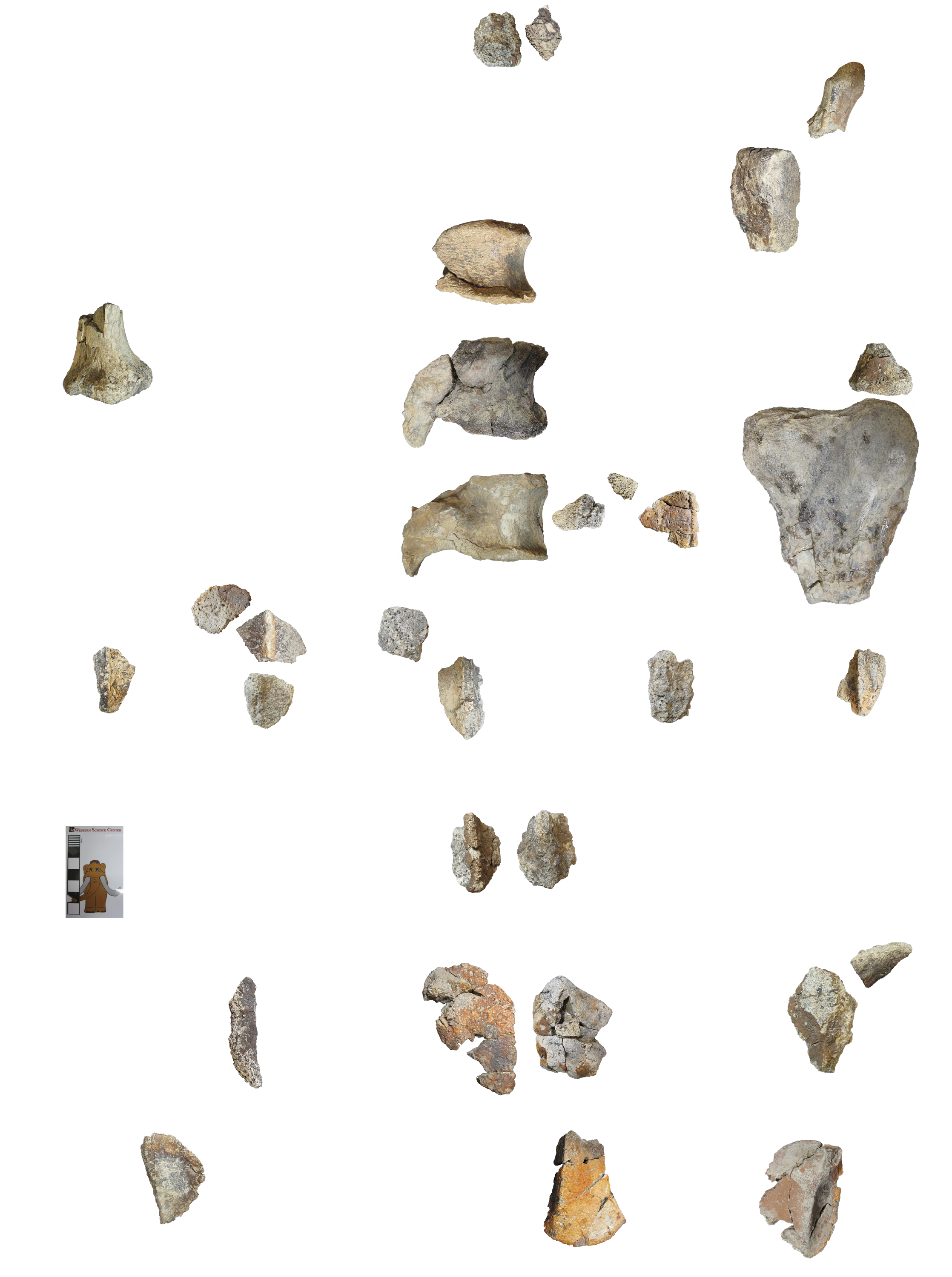

Welcome Invictarx zephyri! This is a very special Fossil Friday for me and everyone here at Western Science Center, and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. The paper naming and describing this new armored plant-eating dinosaur was published today in the online, open-access journal PeerJ. These are the fossils of Invictarx laid out, including vertebrae, parts of the forelimbs, and many osteoderms, the bony armor plates that would have been set in the animal's scaly hide - picture the armored back of an alligator. The image is a composite of three different fossil skeletons found at different spots but in the same rock layer in northwestern New Mexico, and all belonging to Invictarx zephyri.

Welcome Invictarx zephyri! This is a very special Fossil Friday for me and everyone here at Western Science Center, and our colleagues at Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences and Southwest Paleontological Society. The paper naming and describing this new armored plant-eating dinosaur was published today in the online, open-access journal PeerJ. These are the fossils of Invictarx laid out, including vertebrae, parts of the forelimbs, and many osteoderms, the bony armor plates that would have been set in the animal's scaly hide - picture the armored back of an alligator. The image is a composite of three different fossil skeletons found at different spots but in the same rock layer in northwestern New Mexico, and all belonging to Invictarx zephyri. Invictarx lived 80 million years ago, when New Mexico was covered in lush forests, dank swamps, and sluggish rivers, a far cry from the parched badlands in which my colleagues and I found the fossil remains. Invictarx is a nodosaurid, a group of armored dinosaurs that includes many species from North America and Europe. The osteoderms of Invictarx have a unique set of features that set them apart from all other nodosaurids, indicating that we have a new species on our hands, one never found by paleontologists before. Like other nodosaurids, Invictarx sported armor plates across its neck, back, and hips, which probably provided a formidable defense against predators like tyrannosaurs. We collected the first skeleton of Invictarx in 2011, at a site perched atop a high ridge whipped by 40 mile-per-hour winds, which made for a challenging excavation. With all this in mind, my sister and I took out our Latin dictionaries and came up with the name Invictarx zephyri, the "unconquerable fortress of the western wind".

Invictarx lived 80 million years ago, when New Mexico was covered in lush forests, dank swamps, and sluggish rivers, a far cry from the parched badlands in which my colleagues and I found the fossil remains. Invictarx is a nodosaurid, a group of armored dinosaurs that includes many species from North America and Europe. The osteoderms of Invictarx have a unique set of features that set them apart from all other nodosaurids, indicating that we have a new species on our hands, one never found by paleontologists before. Like other nodosaurids, Invictarx sported armor plates across its neck, back, and hips, which probably provided a formidable defense against predators like tyrannosaurs. We collected the first skeleton of Invictarx in 2011, at a site perched atop a high ridge whipped by 40 mile-per-hour winds, which made for a challenging excavation. With all this in mind, my sister and I took out our Latin dictionaries and came up with the name Invictarx zephyri, the "unconquerable fortress of the western wind". Apart from being a fascinating animal in itself, Invictarx is also the first new species of dinosaur named from the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which it was discovered. It is the first of many fossil animals and plants from the Menefee that we will describe over the coming years. Of the three specimens, we chose one to serve as the holotype of Invictarx. The holotype of an organism, living or extinct, is the specimen to which the organism's scientific name will always be attached. It serves as the standard by which all future discoveries will be assessed as to whether they represent the same species as the holotype or not. The holotype is accessioned here at the Western Science Center, and is the first holotype in our collections.

Apart from being a fascinating animal in itself, Invictarx is also the first new species of dinosaur named from the Menefee Formation, the rock layer in which it was discovered. It is the first of many fossil animals and plants from the Menefee that we will describe over the coming years. Of the three specimens, we chose one to serve as the holotype of Invictarx. The holotype of an organism, living or extinct, is the specimen to which the organism's scientific name will always be attached. It serves as the standard by which all future discoveries will be assessed as to whether they represent the same species as the holotype or not. The holotype is accessioned here at the Western Science Center, and is the first holotype in our collections.  My colleagues and I return to New Mexico every summer to search for dinosaurs and other fossils in the Menefee Formation. We will very probably find additional fossils of Invictarx that will tell us more about its appearance and evolution. Naming it was really just the first step!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

My colleagues and I return to New Mexico every summer to search for dinosaurs and other fossils in the Menefee Formation. We will very probably find additional fossils of Invictarx that will tell us more about its appearance and evolution. Naming it was really just the first step!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian horn core

After a successful expedition earlier this summer, the Western Science Center crew returned to the Menefee Formation of New Mexico last week to search for more fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures that roamed the area 80 million years ago. As before, we were joined by colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, students from the University of Arizona - Tucson, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. Unlike the first trip, when we spent most of our time digging at two dinosaur quarries, this trip was mostly spent exploring for new fossil sites.This bone fragment is one of the pieces we collected while prospecting. The outer surface of this piece is riddled with deep branching grooves. This sort of texture is present only on the bony horn cores of ceratopsids, the big horned dinosaurs, such as Triceratops. When the dinosaur was alive, these grooves would have been occupied by blood vessels supplying the sheath of keratin (think fingernails) that covered the bony horn core. The photo shows the Menefee horn core fragment next to the brow horns of Ava, a horned dinosaur skull on display in WSC's "Great Wonders" exhibit. Ava's horns have the same texture.

After a successful expedition earlier this summer, the Western Science Center crew returned to the Menefee Formation of New Mexico last week to search for more fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures that roamed the area 80 million years ago. As before, we were joined by colleagues from the Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, students from the University of Arizona - Tucson, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. Unlike the first trip, when we spent most of our time digging at two dinosaur quarries, this trip was mostly spent exploring for new fossil sites.This bone fragment is one of the pieces we collected while prospecting. The outer surface of this piece is riddled with deep branching grooves. This sort of texture is present only on the bony horn cores of ceratopsids, the big horned dinosaurs, such as Triceratops. When the dinosaur was alive, these grooves would have been occupied by blood vessels supplying the sheath of keratin (think fingernails) that covered the bony horn core. The photo shows the Menefee horn core fragment next to the brow horns of Ava, a horned dinosaur skull on display in WSC's "Great Wonders" exhibit. Ava's horns have the same texture.  We will spend the next year preparing and studying the fossils we brought back from this summer's Menefee expeditions, and we will have much more to say about them in the very near future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

We will spend the next year preparing and studying the fossils we brought back from this summer's Menefee expeditions, and we will have much more to say about them in the very near future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald