Over the last year or so, I've posted many bones from large herbivorous dinosaurs that lived in New Mexico around 79 million years ago, such as duck-billed hadrosaurs, horned ceratopsids, and the armored Invictarx.Alongside the bones of these beasts in the Menefee Formation we often find fossil plants. Many of these occurrences are petrified logs and stumps, which we find eroding out onto the surface.However, sometimes when we dig into the layers of mudstone to excavate dinosaur bones, we also encounter beautiful fossil leaves. The image today is a very nice leaf from a Late Cretaceous fern, probably belonging to the living fern genus Anemia. Fossils like this give us some idea of what the plant-eating dinosaurs might have been eating, and show that back then New Mexico was a much wetter habitat than today. It was a muddy floodplain lush with plants and teeming with dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Over the last year or so, I've posted many bones from large herbivorous dinosaurs that lived in New Mexico around 79 million years ago, such as duck-billed hadrosaurs, horned ceratopsids, and the armored Invictarx.Alongside the bones of these beasts in the Menefee Formation we often find fossil plants. Many of these occurrences are petrified logs and stumps, which we find eroding out onto the surface.However, sometimes when we dig into the layers of mudstone to excavate dinosaur bones, we also encounter beautiful fossil leaves. The image today is a very nice leaf from a Late Cretaceous fern, probably belonging to the living fern genus Anemia. Fossils like this give us some idea of what the plant-eating dinosaurs might have been eating, and show that back then New Mexico was a much wetter habitat than today. It was a muddy floodplain lush with plants and teeming with dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Palm Frond

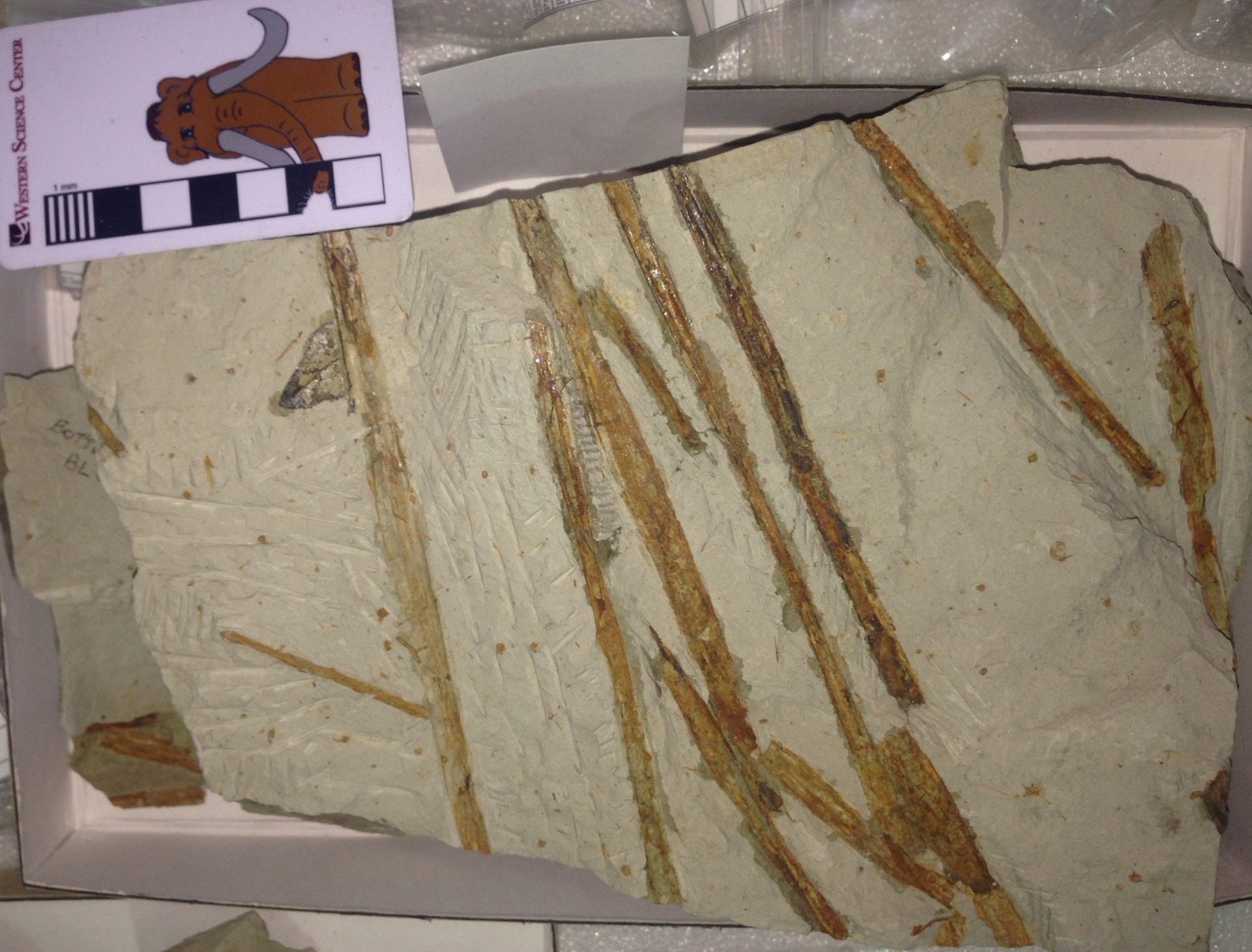

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Palm Leaf

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Annularia

I've spent the last week trying to catch up on administrative work while pouring over all the data we gathered during our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" road trip. But after several weeks of almost all mastodons it gives me the chance to feature a different organism for Fossil Friday. The specimen shown above was donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham College Geology Department, and comes from the famous Carboniferous Period deposits at Mazon Creek in Illinois. While this looks somewhat like a flower, it's actually a whorl of leaves known as Annularia (flowers had not yet evolved in the Carboniferous). Annularia are the leaves of horsetails or scouring rushes, a plant that's still around as the genus Equisetum:

I've spent the last week trying to catch up on administrative work while pouring over all the data we gathered during our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" road trip. But after several weeks of almost all mastodons it gives me the chance to feature a different organism for Fossil Friday. The specimen shown above was donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham College Geology Department, and comes from the famous Carboniferous Period deposits at Mazon Creek in Illinois. While this looks somewhat like a flower, it's actually a whorl of leaves known as Annularia (flowers had not yet evolved in the Carboniferous). Annularia are the leaves of horsetails or scouring rushes, a plant that's still around as the genus Equisetum:

Modern horsetails are small, spore-bearing plants that live primarily in marshy areas. But in the Carboniferous there were giant horsetails that grew to be up to 10 meters tall, and were among the world's most common trees.The name Annularia illustrates a particular difficulty faced by paleobotanists. If you're trying to identify a fossil vertebrate, you face several difficulties related to variability. Bones from different parts of the body look different, and they also vary with age (ontogenetic variation) and sex (sexual dimorphism). Plants present all these same issues, but they may also only grow some structures at certain times of the year (flowers, seeds, spores, pollen), the body parts may easily or even intentionally separate from the rest of the plant (deciduous leaves, seeds, spores, pollen), and preservation potential may be wildly different from one part to another. The result is that, if you have a bunch of fossil leaves and fossil stems, it's often very difficult to tell which ones go together unless that happen to be preserved actually connected to one another. Paleobotanists get around this problem by naming form taxa or organ taxa. The name Annularia specifically refers to leaf whorls of horsetails that share a particular morphology. Other parts of the plant, such as the stems and the spore cones, have different names. Fossil horsetails are quite common and well-known in Carboniferous rocks, so we actually know that fossil stems called Calamites come from the same plants that produce Annularia.

Modern horsetails are small, spore-bearing plants that live primarily in marshy areas. But in the Carboniferous there were giant horsetails that grew to be up to 10 meters tall, and were among the world's most common trees.The name Annularia illustrates a particular difficulty faced by paleobotanists. If you're trying to identify a fossil vertebrate, you face several difficulties related to variability. Bones from different parts of the body look different, and they also vary with age (ontogenetic variation) and sex (sexual dimorphism). Plants present all these same issues, but they may also only grow some structures at certain times of the year (flowers, seeds, spores, pollen), the body parts may easily or even intentionally separate from the rest of the plant (deciduous leaves, seeds, spores, pollen), and preservation potential may be wildly different from one part to another. The result is that, if you have a bunch of fossil leaves and fossil stems, it's often very difficult to tell which ones go together unless that happen to be preserved actually connected to one another. Paleobotanists get around this problem by naming form taxa or organ taxa. The name Annularia specifically refers to leaf whorls of horsetails that share a particular morphology. Other parts of the plant, such as the stems and the spore cones, have different names. Fossil horsetails are quite common and well-known in Carboniferous rocks, so we actually know that fossil stems called Calamites come from the same plants that produce Annularia.

Fossil Friday - bur-reed and other plants

Fossil plants often don't get the attention they deserve, but besides being interesting organisms in their on right, they are in many ways far better indicators of past environmental conditions than are animals.Excavation of the Early- to Middle- Pleistocene deposits at the Southern California Edison El Casco Substation in San Timoteo Canyon produced numerous fossil plants, including quite a few examples of bur-reed (Sparganium sp.) such as the examples shown above. Sparganium is an aquatic plant that grows in marshes and standing water, and while several species still live in California we don't see them in areas as dry as San Timoteo Canyon is today. Several other marsh plants, including horsetails, were also found in these deposits.As I was photographing this specimen, I noticed another plant peaking out from under the bur-reed:

Fossil plants often don't get the attention they deserve, but besides being interesting organisms in their on right, they are in many ways far better indicators of past environmental conditions than are animals.Excavation of the Early- to Middle- Pleistocene deposits at the Southern California Edison El Casco Substation in San Timoteo Canyon produced numerous fossil plants, including quite a few examples of bur-reed (Sparganium sp.) such as the examples shown above. Sparganium is an aquatic plant that grows in marshes and standing water, and while several species still live in California we don't see them in areas as dry as San Timoteo Canyon is today. Several other marsh plants, including horsetails, were also found in these deposits.As I was photographing this specimen, I noticed another plant peaking out from under the bur-reed: I'm pretty sure this is a birch leaf (Betula sp.), which is known from other specimens in the El Casco collection. Betula doesn't require as much water as Sparganium, but it's still not tolerant of arid conditions. However, today Betula is not found naturally anywhere in southern California, and in fact is found nowhere in the southern United States (even in humid areas) except at high elevations. It seems that birch are not tolerant of frequent high temperatures, and thrive in the cooler conditions found today at higher latitudes and altitudes. The presence of birch and abundant water plants such as Sparganium in the El Casco collection suggested wetter and cooler conditions at San Timoteo Canyon during the Early Pleistocene relative to what we see there today.

I'm pretty sure this is a birch leaf (Betula sp.), which is known from other specimens in the El Casco collection. Betula doesn't require as much water as Sparganium, but it's still not tolerant of arid conditions. However, today Betula is not found naturally anywhere in southern California, and in fact is found nowhere in the southern United States (even in humid areas) except at high elevations. It seems that birch are not tolerant of frequent high temperatures, and thrive in the cooler conditions found today at higher latitudes and altitudes. The presence of birch and abundant water plants such as Sparganium in the El Casco collection suggested wetter and cooler conditions at San Timoteo Canyon during the Early Pleistocene relative to what we see there today.

Fossil Friday - Equisetum

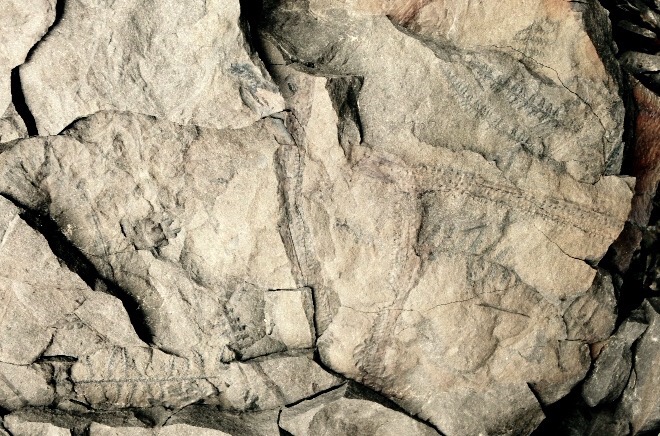

Fossil plants never seem to get the attention they deserve. Fossil animals, especially vertebrates, certainly are fascinating and have tons of things to tell us (they are, after all, what I've worked on for most of my career). But plants are exceptionally good indicators of past environmental conditions, besides being interesting organisms in their own right.Shown above is a sample of the San Timoteo Formation from northern Riverside County, specifically from the Edison El Casco Substation. This excavation yielded several thousand fossils, including plants, animals, and traces, which lived about 1.5 to 2.0 million years ago. The dark brown streaks in this sample are fragments of plant stems. While these don't look like much, there's enough here to make an identification.In the prominent stem toward the upper left, notice the fine grooves and ridges that run lengthwise along the stem (marked with the blue arrow, below). The stem also is divided into segments, marked below with the red arrows:

Fossil plants never seem to get the attention they deserve. Fossil animals, especially vertebrates, certainly are fascinating and have tons of things to tell us (they are, after all, what I've worked on for most of my career). But plants are exceptionally good indicators of past environmental conditions, besides being interesting organisms in their own right.Shown above is a sample of the San Timoteo Formation from northern Riverside County, specifically from the Edison El Casco Substation. This excavation yielded several thousand fossils, including plants, animals, and traces, which lived about 1.5 to 2.0 million years ago. The dark brown streaks in this sample are fragments of plant stems. While these don't look like much, there's enough here to make an identification.In the prominent stem toward the upper left, notice the fine grooves and ridges that run lengthwise along the stem (marked with the blue arrow, below). The stem also is divided into segments, marked below with the red arrows: These are both characteristics of the genus Equisetum, commonly known as the horsetail or scouring rush (the latter name comes from the high silica content, which makes them useful as an abrasive). Equisetum is an interesting plant, the last survivor of a group that goes back more than 350 million years. Rather than seeds they reproduce using spores, which are released from a cone-like structure (the sporangium) at the top of the plant. (There may be an impression of a sporangium attached to the stem in this specimen, but I'm uncertain about that.) Horsetails seem to be related to ferns, and according to some genetic studies may actually be highly specialized ferns. Below are some modern examples of the whole plant (at least the above-ground portions), one of which has grown its sporangium. Notice the segmented, striated stems, just as in our fossil example:

These are both characteristics of the genus Equisetum, commonly known as the horsetail or scouring rush (the latter name comes from the high silica content, which makes them useful as an abrasive). Equisetum is an interesting plant, the last survivor of a group that goes back more than 350 million years. Rather than seeds they reproduce using spores, which are released from a cone-like structure (the sporangium) at the top of the plant. (There may be an impression of a sporangium attached to the stem in this specimen, but I'm uncertain about that.) Horsetails seem to be related to ferns, and according to some genetic studies may actually be highly specialized ferns. Below are some modern examples of the whole plant (at least the above-ground portions), one of which has grown its sporangium. Notice the segmented, striated stems, just as in our fossil example: Equisetum also has interesting things to tell us about its ecosystem. Here's a group of modern Equisetum in their typical natural habitat:

Equisetum also has interesting things to tell us about its ecosystem. Here's a group of modern Equisetum in their typical natural habitat: Equisetum loves water, and typically grows in or near ponds or marshes. It seems to be one of the more common plants in the El Casco Substation deposits, and is found with a number of other plant species that prefer similar conditions. This all suggests that, at least locally, conditions there were much wetter than they are today.

Equisetum loves water, and typically grows in or near ponds or marshes. It seems to be one of the more common plants in the El Casco Substation deposits, and is found with a number of other plant species that prefer similar conditions. This all suggests that, at least locally, conditions there were much wetter than they are today.

Fossil Friday - Carboniferous plants

Last week I made a short trip back to Virginia for my son's graduation from Patrick Henry Community College. This also was a perfect opportunity for some fossil collecting, so Brett, Tim, and I met DorothyBelle Poli and Lisa Stoneman from Roanoke College for a day trip to Beckley, West Virginia.Boxley Materials operates a quarry near Beckley that cuts through the Carboniferous (~ 318 million-year-old) New River Formation. Certain beds of the New River Formation are full of fossil plants, and Boxley set aside some of this material for us to examine. Like many Carboniferous forests, one of the most prominent types of plants in these deposits is giant lycopods. Above is an example of Stigmaria, part of the root system of these lycopods (because it's rare to find all the parts of a plant in a single fossil, different fossil plant structures often have different scientific names). Unfortunately, this Stigmaria was in a rock that was far too large for us to collect.Giant lycopods are sometimes called "scale trees" because of the geometric (often diamond-shaped) leaf scars on their trunks:

Last week I made a short trip back to Virginia for my son's graduation from Patrick Henry Community College. This also was a perfect opportunity for some fossil collecting, so Brett, Tim, and I met DorothyBelle Poli and Lisa Stoneman from Roanoke College for a day trip to Beckley, West Virginia.Boxley Materials operates a quarry near Beckley that cuts through the Carboniferous (~ 318 million-year-old) New River Formation. Certain beds of the New River Formation are full of fossil plants, and Boxley set aside some of this material for us to examine. Like many Carboniferous forests, one of the most prominent types of plants in these deposits is giant lycopods. Above is an example of Stigmaria, part of the root system of these lycopods (because it's rare to find all the parts of a plant in a single fossil, different fossil plant structures often have different scientific names). Unfortunately, this Stigmaria was in a rock that was far too large for us to collect.Giant lycopods are sometimes called "scale trees" because of the geometric (often diamond-shaped) leaf scars on their trunks: Seed ferns are also widespread in Carboniferous deposits; there are several different species in this sample:

Seed ferns are also widespread in Carboniferous deposits; there are several different species in this sample: We are able to collect several good specimens for the Western Science Center, which will be nice additions to our growing paleobotany collection.

We are able to collect several good specimens for the Western Science Center, which will be nice additions to our growing paleobotany collection.

Fossil Friday - Carboniferous plant donation

During my trip to the Midwest last month I made a brief stop at Earlham College in Indiana, where I have a lot of longtime friends and where I've done some work in the past with their excellent campus museum, the Joseph Moore Museum. While at Earlham I picked up a collection of fossil plants that were donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham Geology Department.

During my trip to the Midwest last month I made a brief stop at Earlham College in Indiana, where I have a lot of longtime friends and where I've done some work in the past with their excellent campus museum, the Joseph Moore Museum. While at Earlham I picked up a collection of fossil plants that were donated to the Western Science Center by the Earlham Geology Department. The majority of these plants are from a world famous locality in Illinois called Mazon Creek, which includes sediments from the Late Carboniferous Period (approximately 300 million years old). Through a combination of rapid burial and unusual geochemical conditions organic material at Mazon Creek was exquisitely preserved in hard concretions. The vast majority of the Mazon Creek fossils are plants (and the collections donated to WSC only includes plants) but many animals have also been recovered, including marine invertebrates (even soft-bodied jellyfish), insects and other terrestrial invertebrates, and occasional fish and sharks.It will take us awhile to sort and identify all the specimens in the donation, which included several boxes of material. The WSC previously had almost no Carboniferous fossils in our collection, so this is a very nice addition. I'd like to thank Andrew Moore and Cynthia Fadem of the Earlham College Geology Department for arranging for the donation of this wonderful collection.

The majority of these plants are from a world famous locality in Illinois called Mazon Creek, which includes sediments from the Late Carboniferous Period (approximately 300 million years old). Through a combination of rapid burial and unusual geochemical conditions organic material at Mazon Creek was exquisitely preserved in hard concretions. The vast majority of the Mazon Creek fossils are plants (and the collections donated to WSC only includes plants) but many animals have also been recovered, including marine invertebrates (even soft-bodied jellyfish), insects and other terrestrial invertebrates, and occasional fish and sharks.It will take us awhile to sort and identify all the specimens in the donation, which included several boxes of material. The WSC previously had almost no Carboniferous fossils in our collection, so this is a very nice addition. I'd like to thank Andrew Moore and Cynthia Fadem of the Earlham College Geology Department for arranging for the donation of this wonderful collection.