For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

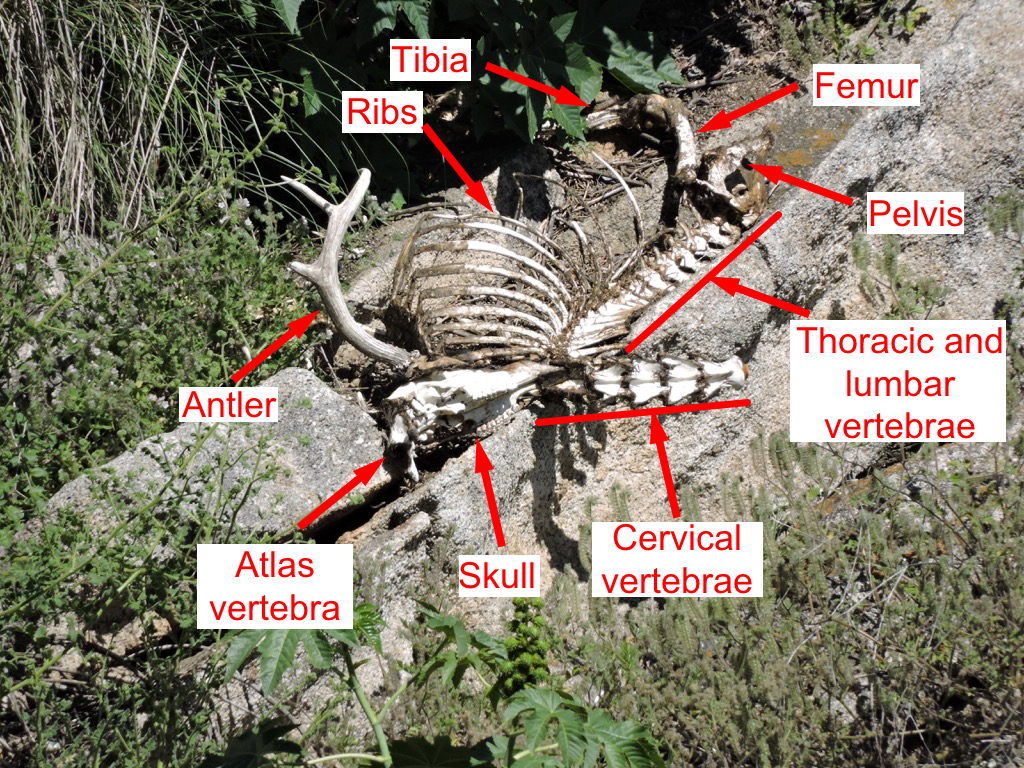

An important aspect of planning an effective exhibit is developing a theme. An exhibit is telling a story, and you need to be aware of what that story is as the exhibit is being designed. The theme might be "We have a bunch of stuff!", but while that was a common theme in museums a century ago (and one I personally appreciate), it does not generally make for the most informative exhibit experience for the majority of visitors.Once the theme is established, it's important to stick to it, so that the exhibit story remains coherent. Imagine reading a mystery novel in which three chapters are devoted to a history of the development of the gunpowder used in the crime, and an additional chapter describes the etymology of the last name of the victim, when neither is important to the outcome of the story. Each of these things might be individually interesting, but if you try to talk about all of them then you risk obscuring everything. There is a real risk of this "mission creep" in an exhibit based on a data-rich field such as paleontology. We might talk about evolutionary relationships, paleoenvironmental indicators, biogeographic information, site-specific descriptions, or an array of other things. Talking about any of these might be a good idea; talking about all of them is a bad idea.The permanent paleontology exhibit at WSC does this very well. The exhibit is basically a review of the Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna; what was here, how does it compare to the rest of Southern California, and (as a secondary point) what does it tell us about the local Pleistocene paleoenvironment. In contrast, "Stories from Bones" asks "What do these fossils tell us about the lives and deaths of these individual animals?".To that end, "Stories" has a series of displays that talk about how paleontologists determine how old an animal was when it died. We have several cases that look at tooth replacement in proboscideans, horses, and bison, such as the two mammoth jaws above (they're close to the same size, but one animal was about 30 years older than the other), or the three bison dentaries shown below that represent young, middle-aged, and elderly animals.

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

We have several examples of bones that were broken and healed, evidence of events that took place during an animal's life:

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

We also have several cases that describe taphonomic features, looking at what happened to an animal at or immediately after death.We designed and built a number of interactive displays for this exhibit. The most prominent is a cast and video of the CT scans of Max the Mastodon's lower jaw, taken back in August.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

We're proud of the fact that several of our interactive displays ask visitors to map or measure specimens and reach conclusions based on their data:

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

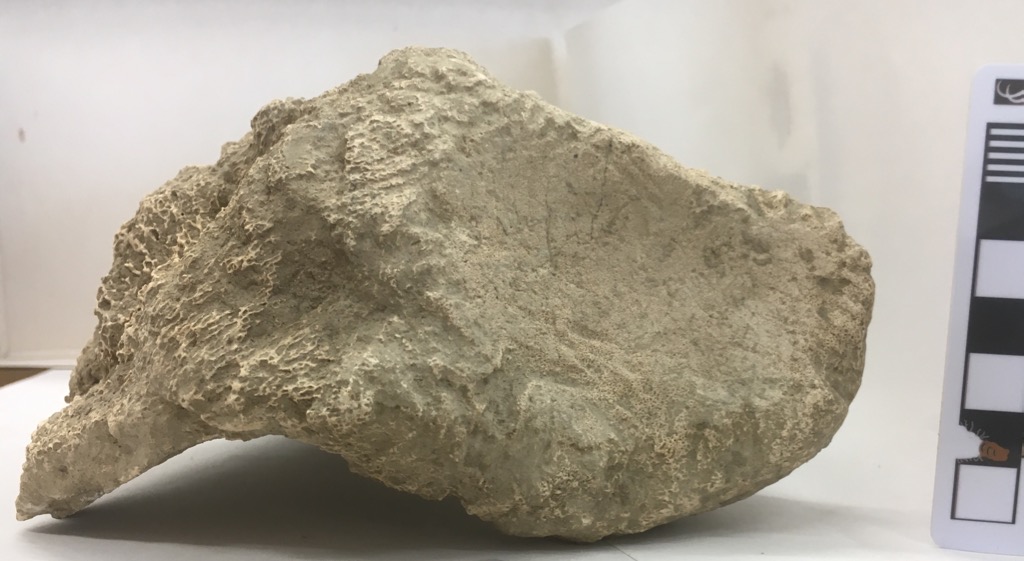

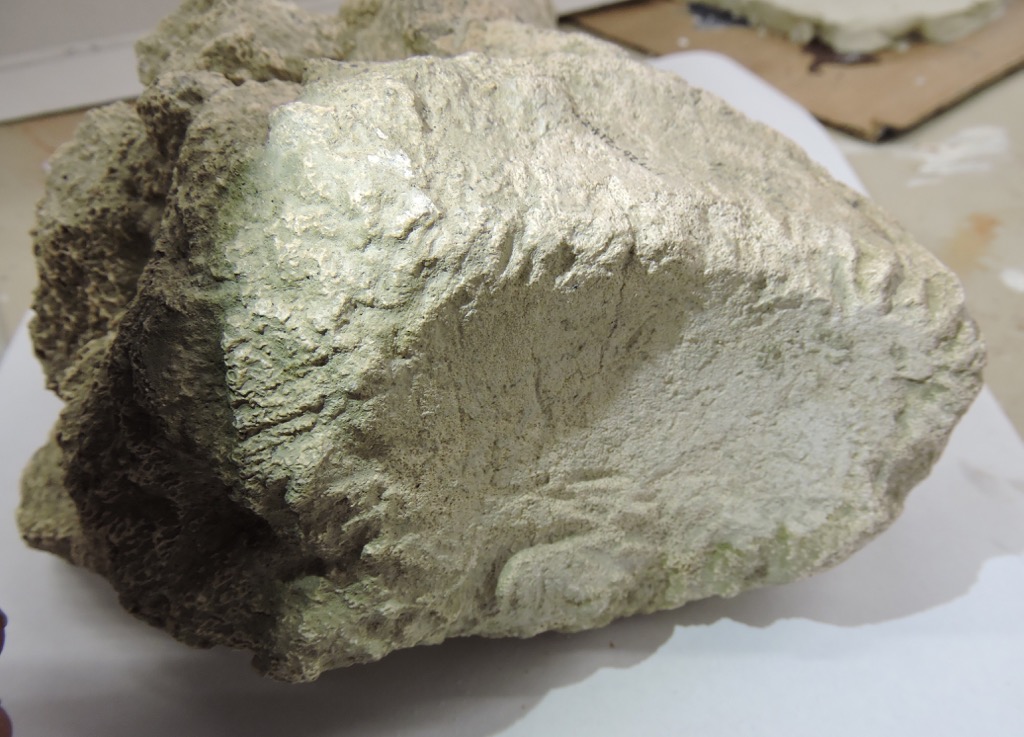

Over the last few weeks we've started pulling a lot of mastodon material from the collections (more on that in a future post). Some of the bones that are turning up are pretty interesting.The large bone fragment shown above is a small part of the proximal end of the right ulna, one of the bones in the forearm. It's shown above in lateral view, and below is looking at the proximal end (part of the articular surface for the elbow):

Over the last few weeks we've started pulling a lot of mastodon material from the collections (more on that in a future post). Some of the bones that are turning up are pretty interesting.The large bone fragment shown above is a small part of the proximal end of the right ulna, one of the bones in the forearm. It's shown above in lateral view, and below is looking at the proximal end (part of the articular surface for the elbow): This fragment is labeled at mastodon, but comparing it to the photos in Olsen (1972) it seems to be closer to a mammoth (below). We'll have to examine it more closely and see if there's any associated material to determine for sure which taxon it belongs to

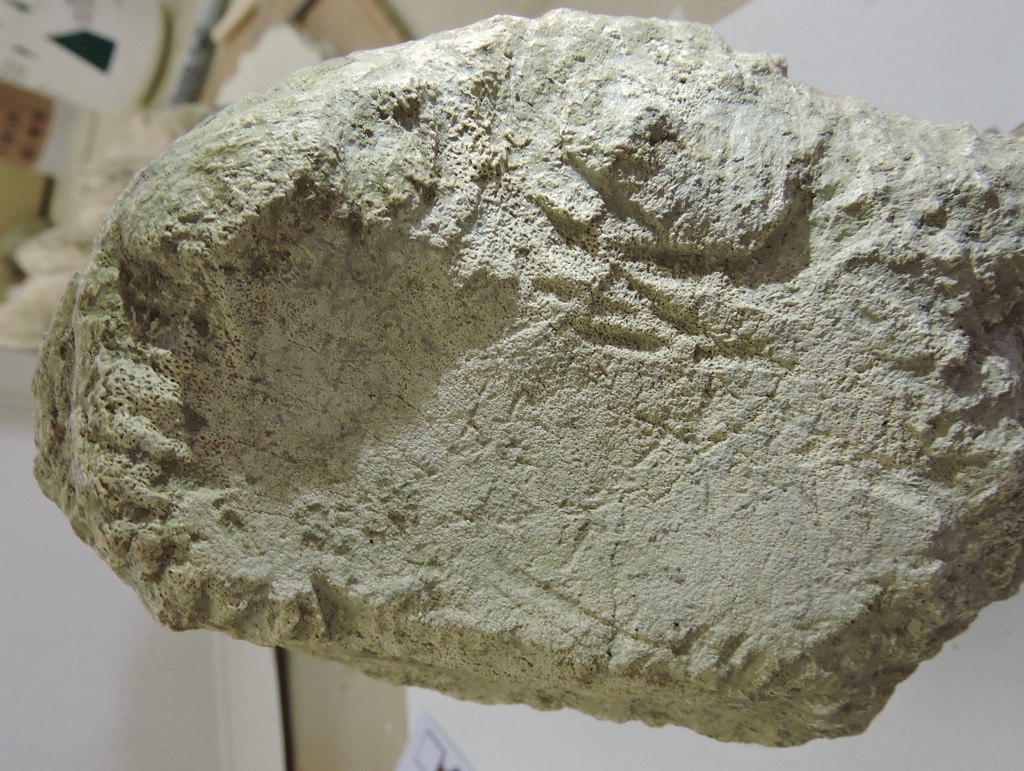

This fragment is labeled at mastodon, but comparing it to the photos in Olsen (1972) it seems to be closer to a mammoth (below). We'll have to examine it more closely and see if there's any associated material to determine for sure which taxon it belongs to What really caught my attention were details on the edges of the articular surface and a few other places on the bone:

What really caught my attention were details on the edges of the articular surface and a few other places on the bone:

As we're finding with many of the large bones from Diamond Valley Lake, this bone is covered with bite marks from scavengers, in the form of notches cut into the edges of the bone. These are relatively large grooves, consistent in size with something like a coyote or dire wolf, but there are lots of possibilities.

As we're finding with many of the large bones from Diamond Valley Lake, this bone is covered with bite marks from scavengers, in the form of notches cut into the edges of the bone. These are relatively large grooves, consistent in size with something like a coyote or dire wolf, but there are lots of possibilities.