Pumpkins are an interesting fruit. Curcurbita pepo is one of several domesticated species of the genus Curcurbita, vines that are native to the Americas. Curcurbita is a ecologically diverse genus, with some species needing a continuous water supply while others can live in arid conditions, so it is found natively in a variety of habitats. The fruits, which are technically berries, generally have a thick rind with a softer interior where the seeds are located. In most species the rinds are bitter, but the interior is often more palatable and rich in nutrients. As a result it became one of the first domesticated plants in North America more than 8,000 years ago.With large, nutritious fruits, we can be confident that wild Curcurbita were being eaten by more than just humans. In 2006 Lee Newsom and Matthew Mihlbachler published a detailed report about an American mastodon dung deposit in northern Florida. The vast majority of the dung consisted of small cypress twigs, chopped up and stripped of bark, but there were other plant remains from at least 57 species. Among their samples were 156 Curcurbita seeds, showing that this was a popular item on the mastodon menu. Using the Newsom and Mihlbachler paper as a guide, a few years ago we made a simulated piece of mastodon dung for exhibit at WSC, including numerous pumpkin and squash seeds:

Pumpkins are an interesting fruit. Curcurbita pepo is one of several domesticated species of the genus Curcurbita, vines that are native to the Americas. Curcurbita is a ecologically diverse genus, with some species needing a continuous water supply while others can live in arid conditions, so it is found natively in a variety of habitats. The fruits, which are technically berries, generally have a thick rind with a softer interior where the seeds are located. In most species the rinds are bitter, but the interior is often more palatable and rich in nutrients. As a result it became one of the first domesticated plants in North America more than 8,000 years ago.With large, nutritious fruits, we can be confident that wild Curcurbita were being eaten by more than just humans. In 2006 Lee Newsom and Matthew Mihlbachler published a detailed report about an American mastodon dung deposit in northern Florida. The vast majority of the dung consisted of small cypress twigs, chopped up and stripped of bark, but there were other plant remains from at least 57 species. Among their samples were 156 Curcurbita seeds, showing that this was a popular item on the mastodon menu. Using the Newsom and Mihlbachler paper as a guide, a few years ago we made a simulated piece of mastodon dung for exhibit at WSC, including numerous pumpkin and squash seeds: Newsom and Mihlbachler also noted that, while Curcurbita seeds were relatively common in their sample, rind fragments were almost completely absent. It seems that mastodons may have disliked the bitter rinds just like we do, and broken the gourds open to get at the interior. Captive elephants that are fed pumpkins seem to have discovered the same trick:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CzXH2Eg1hw&w=560&h=315]So far no Pacific mastodon coprolites have been identified, but hopefully one day we'll be able so say as much about their dietary habits.Reference:Lee Newsom and Matthew C. Mihlbachler, 2006. Mastodon (Mammut americanum) diet and foraging patterns based on analysis of dung deposits. Chapter 10 in S. David Webb (ed.), First Floridians and Last Mastodons: The Page-Ladson Site in the Aucilla River, Springer, p. 263-331.

Newsom and Mihlbachler also noted that, while Curcurbita seeds were relatively common in their sample, rind fragments were almost completely absent. It seems that mastodons may have disliked the bitter rinds just like we do, and broken the gourds open to get at the interior. Captive elephants that are fed pumpkins seem to have discovered the same trick:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CzXH2Eg1hw&w=560&h=315]So far no Pacific mastodon coprolites have been identified, but hopefully one day we'll be able so say as much about their dietary habits.Reference:Lee Newsom and Matthew C. Mihlbachler, 2006. Mastodon (Mammut americanum) diet and foraging patterns based on analysis of dung deposits. Chapter 10 in S. David Webb (ed.), First Floridians and Last Mastodons: The Page-Ladson Site in the Aucilla River, Springer, p. 263-331.

Fossil Friday - Coelacanth fossil

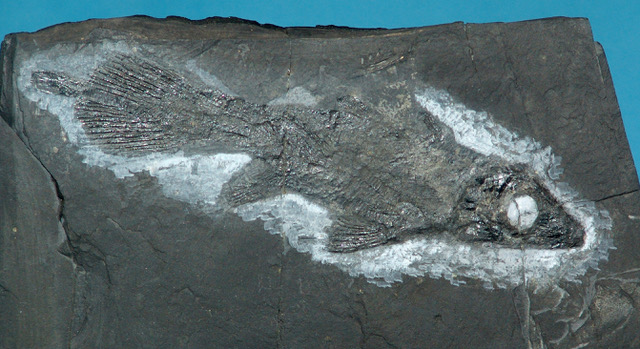

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Potential traces everywhere

I haven't had a lot of free time over this summer, what with moving across the country and starting a new job. Even so, I've been slowly working my way through an excellent book on traces and trace fossils, "Life Traces of the Georgia Coast" by Anthony Martin (@ichnologist on Twitter). Due to the insidious influence of this book, I now find myself looking for traces all the time.A few days ago when I was leaving work I spooked a rabbit (probably a desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audobonii) that was hiding in the grass beside the museum. Having just read the chapter in "Life Traces" that included rabbit traces I decided to see if this rabbit had left behind any evidence of its presence.Most of the Western Science Center grounds are landscaped with native, drought-resistant vegetation. The grasses along the edge of the building are mostly deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens), a bunchgrass that grows in dense clumps, and when I saw the rabbit it was running from a patch of deergrass. When I saw the grasses from above, I noticed that the middle of some of the clumps were brown and missing blades (top). Here's a closeup of the middle of one of the clumps:

I haven't had a lot of free time over this summer, what with moving across the country and starting a new job. Even so, I've been slowly working my way through an excellent book on traces and trace fossils, "Life Traces of the Georgia Coast" by Anthony Martin (@ichnologist on Twitter). Due to the insidious influence of this book, I now find myself looking for traces all the time.A few days ago when I was leaving work I spooked a rabbit (probably a desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audobonii) that was hiding in the grass beside the museum. Having just read the chapter in "Life Traces" that included rabbit traces I decided to see if this rabbit had left behind any evidence of its presence.Most of the Western Science Center grounds are landscaped with native, drought-resistant vegetation. The grasses along the edge of the building are mostly deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens), a bunchgrass that grows in dense clumps, and when I saw the rabbit it was running from a patch of deergrass. When I saw the grasses from above, I noticed that the middle of some of the clumps were brown and missing blades (top). Here's a closeup of the middle of one of the clumps:

The center of the clump was covered with mashed-down, broken blades of grass, over an area of roughly 25 cm by 10 cm. Around the margin of the flattened area there was a dense patch of erect bases of grass blades, clipped off to a height of around 10 cm. The clipped grasses were concentrated on each side of the flattened area, so that the flat area was mostly open on each end of the long axis.A quick survey showed that about 1/3 of the deergrass bunches had these patches in their centers, although there was a lot of variation in their size, and especially in the amount of clipped-off blades. Some patches had only a very small number of clipped blades, although all of them had at least a few. It's interesting that these clipped and flattened areas are only visible when seen from above. When seen from the side the tall grass around the margins of the clumps hide the flat patches at the center.I suspect that the rabbits are eating out the centers of the clumps and using them as hiding places. A rabbit hunkering down in the center of a clump would be completely invisible to predators like coyotes, and while a rattlesnake might be able to sense the rabbit's body heat it might have a hard time finding a way into the center of the clump.So far I haven't found any additional traces to confirm my interpretation. I haven't spotted any rabbit fur or droppings in the clumps (and I'm a little hesitant to stick my hand into them blind, because of the possibility of the aforementioned rattlesnakes). Hopefully one day I'll get better confirmation, like actually seeing a rabbit sitting in the clear patch, chowing down on deergrass.

The center of the clump was covered with mashed-down, broken blades of grass, over an area of roughly 25 cm by 10 cm. Around the margin of the flattened area there was a dense patch of erect bases of grass blades, clipped off to a height of around 10 cm. The clipped grasses were concentrated on each side of the flattened area, so that the flat area was mostly open on each end of the long axis.A quick survey showed that about 1/3 of the deergrass bunches had these patches in their centers, although there was a lot of variation in their size, and especially in the amount of clipped-off blades. Some patches had only a very small number of clipped blades, although all of them had at least a few. It's interesting that these clipped and flattened areas are only visible when seen from above. When seen from the side the tall grass around the margins of the clumps hide the flat patches at the center.I suspect that the rabbits are eating out the centers of the clumps and using them as hiding places. A rabbit hunkering down in the center of a clump would be completely invisible to predators like coyotes, and while a rattlesnake might be able to sense the rabbit's body heat it might have a hard time finding a way into the center of the clump.So far I haven't found any additional traces to confirm my interpretation. I haven't spotted any rabbit fur or droppings in the clumps (and I'm a little hesitant to stick my hand into them blind, because of the possibility of the aforementioned rattlesnakes). Hopefully one day I'll get better confirmation, like actually seeing a rabbit sitting in the clear patch, chowing down on deergrass.