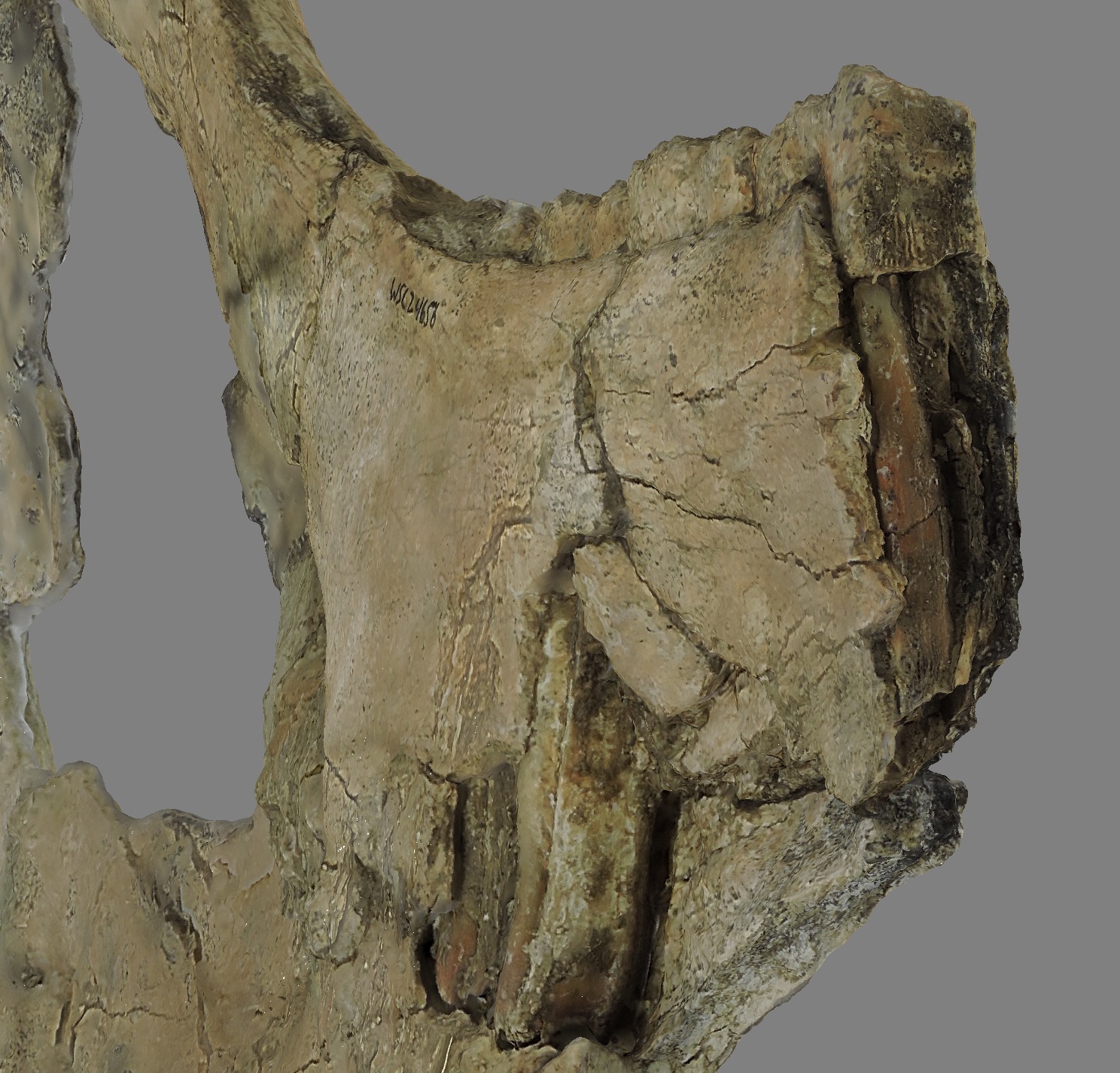

Fossil Friday this week continues our examination of Pleistocene specimens from Temecula Valley, this time with a partial lower jaw from the horse Equus occidentalis.The image above was prepared for our poster at next month's regional GSA meeting in Flagstaff. It shows the dentary in medial, dorsal, and lateral views. The scale bar is 10 cm. In the dorsal view, you can see the occlusal surfaces of the last four teeth in the jaw, which in this case are (from front to back) the 4th deciduous premolar, and molars 1, 2, and 3. The 3rd molar had only just started to erupt, suggesting that this horse was about 3.5 years old when it died. In an oblique anteromedial view (actually a screenshot from a photogrammetric model), you can see the unerupted 4th premolar underneath the 4th deciduous premolar, and, in the background, the deep crown of the 2nd molar where the side of the jaw is broken:

Fossil Friday this week continues our examination of Pleistocene specimens from Temecula Valley, this time with a partial lower jaw from the horse Equus occidentalis.The image above was prepared for our poster at next month's regional GSA meeting in Flagstaff. It shows the dentary in medial, dorsal, and lateral views. The scale bar is 10 cm. In the dorsal view, you can see the occlusal surfaces of the last four teeth in the jaw, which in this case are (from front to back) the 4th deciduous premolar, and molars 1, 2, and 3. The 3rd molar had only just started to erupt, suggesting that this horse was about 3.5 years old when it died. In an oblique anteromedial view (actually a screenshot from a photogrammetric model), you can see the unerupted 4th premolar underneath the 4th deciduous premolar, and, in the background, the deep crown of the 2nd molar where the side of the jaw is broken: We've made a photogrammetric model of this specimen, and printed a 3d replica that we've already started using in programming:

We've made a photogrammetric model of this specimen, and printed a 3d replica that we've already started using in programming: The 3D file of this specimen is available for download at WSC's Sketchfab site at https://skfb.ly/6yCx8.

The 3D file of this specimen is available for download at WSC's Sketchfab site at https://skfb.ly/6yCx8.

Fossil Friday - horse scapula

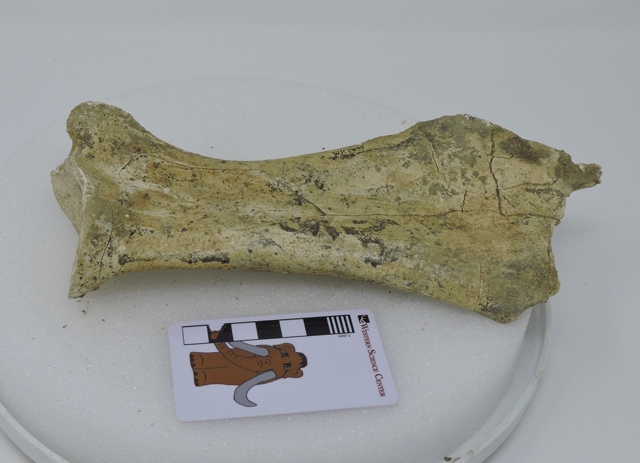

This week we continue our documentation of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston section of Murrieta, California, with a horse scapula.This specimen is a partial right scapula, shown above in medial view. It's missing a small part of the dorsal edge, on the right in the photo. The part of the scapula is cartilaginous in young animals, and actually only ossifies fairly late in ontogeny, so it's not unusual to be missing this area.

This week we continue our documentation of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston section of Murrieta, California, with a horse scapula.This specimen is a partial right scapula, shown above in medial view. It's missing a small part of the dorsal edge, on the right in the photo. The part of the scapula is cartilaginous in young animals, and actually only ossifies fairly late in ontogeny, so it's not unusual to be missing this area. The lateral view is shown above, with anterior at the bottom (this image is missing the scale bar because these are part of a set used to produce a photogrammetric model). The surface on the left is the edge of the glenoid fossa, the articulation with the head of the humerus (the "shoulder socket"). A bone ridge, called the scapular spine, is pointing straight at the camera and divides the scapula into concave anterior and posterior surfaces. The anterior portion is called the supraspinatus fossa, while the posterior part is the infraspinatus fossa; each serves as the attachment points for muscles of the same names, that are involved in rotating the forelimb.I've uploaded a 3D model of this specimen on Sketchfab, available at https://skfb.ly/6y9VM.

The lateral view is shown above, with anterior at the bottom (this image is missing the scale bar because these are part of a set used to produce a photogrammetric model). The surface on the left is the edge of the glenoid fossa, the articulation with the head of the humerus (the "shoulder socket"). A bone ridge, called the scapular spine, is pointing straight at the camera and divides the scapula into concave anterior and posterior surfaces. The anterior portion is called the supraspinatus fossa, while the posterior part is the infraspinatus fossa; each serves as the attachment points for muscles of the same names, that are involved in rotating the forelimb.I've uploaded a 3D model of this specimen on Sketchfab, available at https://skfb.ly/6y9VM.

Fossil Friday - Snake Vertebra

In the opinion of this naturalist, snakes are among the most elegant animals ever to have evolved. The fossil record of extinct snakes was poorly known for a long time. However, recent discoveries have revealed that a diverse array of early snakes lived alongside the dinosaurs, as far back in time as the Middle Jurassic Epoch, over 165 million years ago. The earliest known snake is Eophis underwoodi, from the Middle Jurassic of England: http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms6996Today's Fossil Friday subject is a fossil snake in the Western Science Center's collection. This is a vertebra of Coniophis precedens, a snake that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch, about 67 million years ago, alongside much bigger reptiles such as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. This specimen was collected by the late Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary.

In the opinion of this naturalist, snakes are among the most elegant animals ever to have evolved. The fossil record of extinct snakes was poorly known for a long time. However, recent discoveries have revealed that a diverse array of early snakes lived alongside the dinosaurs, as far back in time as the Middle Jurassic Epoch, over 165 million years ago. The earliest known snake is Eophis underwoodi, from the Middle Jurassic of England: http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms6996Today's Fossil Friday subject is a fossil snake in the Western Science Center's collection. This is a vertebra of Coniophis precedens, a snake that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch, about 67 million years ago, alongside much bigger reptiles such as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. This specimen was collected by the late Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary.

These early snakes were not venomous, but instead killed their prey by constriction like living pythons and boas. Another Late Cretaceous snake, Sanajeh indicus from India, seems to have habitually preyed upon hatchling long-necked sauropod dinosaurs. Three skeletons of this snake have been discovered associated with fossils of sauropod nests, eggs, and hatchlings: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1000322

Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - juvenile Tyrannosaurus

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - camel elbow

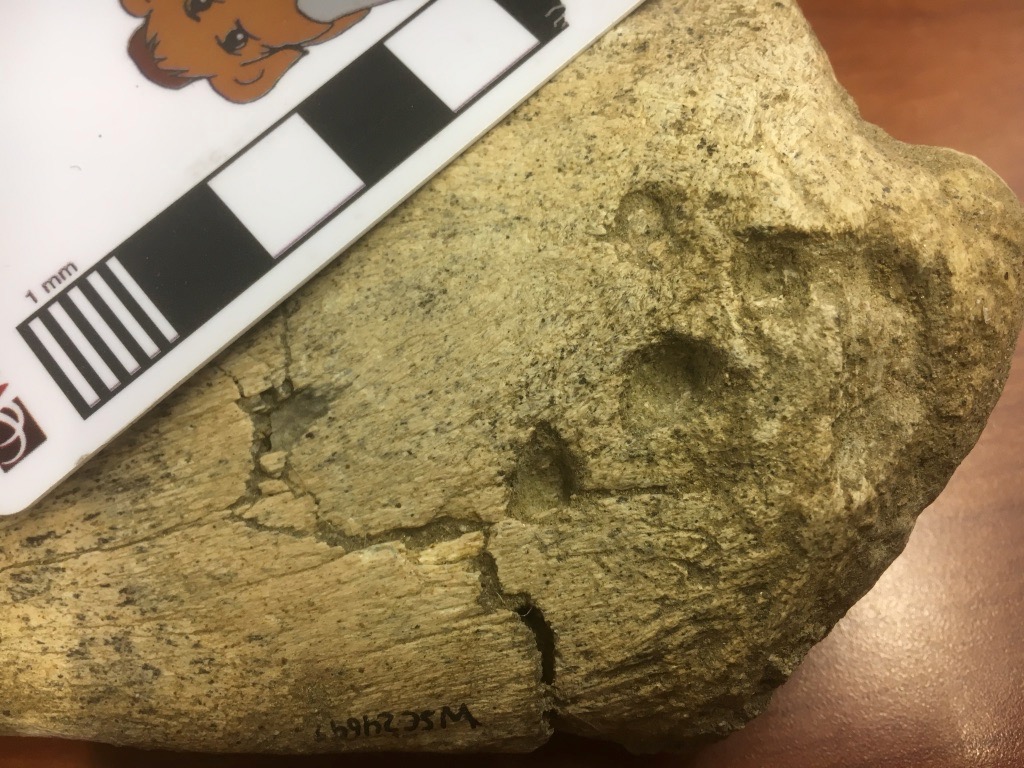

We're continuing our focus on Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, California this week with a single bone fragment that has a lot going on.This bone is labeled in our collections as an ulna from Equus, a horse. It is indeed part of a left ulna, one of the bones from the forearm. More specifically, it's the olecranon process, the proximal end of the ulna that forms the point of the elbow. The triceps muscle attaches to the olecranon process, allowing you to straighten your arm (or front leg, in this case). However, after spending several hours comparing this to various publications and our Diamond Valley Lake collections, I'm not convinced it's a horse.For an olecranon process of this size, there are really only three likely animals from the Pleistocene of Southern California it could belong to: horse, camel, and bison. Everything else is either much larger (mammoth, mastodon) or much smaller (mule deer). (OK, to be fair, short-faced bears and ground sloths are in this size range, but their ulnae look nothing like this.) Horses, camels, and bison are all known from this site, but while it's a little on the small side, this bone is the best match with the western camel, Camelops hesternus.There is another interesting feature on this bone. Notice the four circular depressions near the tip (on the right). Here's a closeup:

We're continuing our focus on Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, California this week with a single bone fragment that has a lot going on.This bone is labeled in our collections as an ulna from Equus, a horse. It is indeed part of a left ulna, one of the bones from the forearm. More specifically, it's the olecranon process, the proximal end of the ulna that forms the point of the elbow. The triceps muscle attaches to the olecranon process, allowing you to straighten your arm (or front leg, in this case). However, after spending several hours comparing this to various publications and our Diamond Valley Lake collections, I'm not convinced it's a horse.For an olecranon process of this size, there are really only three likely animals from the Pleistocene of Southern California it could belong to: horse, camel, and bison. Everything else is either much larger (mammoth, mastodon) or much smaller (mule deer). (OK, to be fair, short-faced bears and ground sloths are in this size range, but their ulnae look nothing like this.) Horses, camels, and bison are all known from this site, but while it's a little on the small side, this bone is the best match with the western camel, Camelops hesternus.There is another interesting feature on this bone. Notice the four circular depressions near the tip (on the right). Here's a closeup: There are a few comparable depressions on the other side:

There are a few comparable depressions on the other side: These appear to be bite marks, from some carnivoran chewing on the end of the bone. There are several other scrapes that appear to be gnaw marks. So far we have not identified any carnivoran bones from this site, but they certainly made their presence felt.We have scanned and 3D-printed this bone (print shown below with the original), and the scans can be viewed on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6xNMM.

These appear to be bite marks, from some carnivoran chewing on the end of the bone. There are several other scrapes that appear to be gnaw marks. So far we have not identified any carnivoran bones from this site, but they certainly made their presence felt.We have scanned and 3D-printed this bone (print shown below with the original), and the scans can be viewed on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6xNMM.

Fossil Friday - amiid fish jaws

At the close of the age of dinosaurs in North America, dry land was prowled by a variety of large and small dinosaurian predators, such as Tyrannosaurus and dromaeosaurs, a.k.a. the raptors. The freshwater streams and lakes were home to very different, but no less voracious, meat-eaters. These bone fragments are pieces of the lower jaws of amiid fish. Amiids are a group of bony fishes with a long fossil record, but which today are restricted to a single surviving species, the bowfin (Amia calva), which hunts in the waterways of eastern North America. (Example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History.)

At the close of the age of dinosaurs in North America, dry land was prowled by a variety of large and small dinosaurian predators, such as Tyrannosaurus and dromaeosaurs, a.k.a. the raptors. The freshwater streams and lakes were home to very different, but no less voracious, meat-eaters. These bone fragments are pieces of the lower jaws of amiid fish. Amiids are a group of bony fishes with a long fossil record, but which today are restricted to a single surviving species, the bowfin (Amia calva), which hunts in the waterways of eastern North America. (Example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History.) These two fragments of lower jaws do not contain any preserved teeth, but clearly show the empty sockets for the teeth. Amiids are carnivorous, and wield a mouth full of formidable teeth for snaring prey, as shown in this bowfin skull at Ohio State University:

These two fragments of lower jaws do not contain any preserved teeth, but clearly show the empty sockets for the teeth. Amiids are carnivorous, and wield a mouth full of formidable teeth for snaring prey, as shown in this bowfin skull at Ohio State University: https://u.osu.edu/biomuseum/olympus-digital-camera-6/These jaw fragments were collected by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, which dates to the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 67 million years ago. They were donated to the Western Science Center by Mary Garbani.

https://u.osu.edu/biomuseum/olympus-digital-camera-6/These jaw fragments were collected by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, which dates to the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 67 million years ago. They were donated to the Western Science Center by Mary Garbani.

Fossil Friday - horse molar

As we continue to work on WSC's collection of Late Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, it has become clear that, while the collection my be taxonomically diverse, it contains a lot of horse bones!The specimen shown above is a lower right first molar of the horse Equus occidentalis in lateral (labial) view. On the left is an unpainted 3D print of the same specimen. Below is the same specimen in occlusal view:

As we continue to work on WSC's collection of Late Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, it has become clear that, while the collection my be taxonomically diverse, it contains a lot of horse bones!The specimen shown above is a lower right first molar of the horse Equus occidentalis in lateral (labial) view. On the left is an unpainted 3D print of the same specimen. Below is the same specimen in occlusal view: Horses are highly hypsodont, meaning they have very tall, high-crowned teeth. As you can see in the lateral view at the top, we have both the roots and the occlusal surface preserved, showing that we have the whole tooth (it's not broken), yet the tooth is quite short. That's because almost this entire tooth has been worn away, indicating that it came from a very elderly horse.We've obviously scanned this tooth, since we've 3D-printed it. We've also made the scan available on Sketchfab:https://skfb.ly/6xyuR

Horses are highly hypsodont, meaning they have very tall, high-crowned teeth. As you can see in the lateral view at the top, we have both the roots and the occlusal surface preserved, showing that we have the whole tooth (it's not broken), yet the tooth is quite short. That's because almost this entire tooth has been worn away, indicating that it came from a very elderly horse.We've obviously scanned this tooth, since we've 3D-printed it. We've also made the scan available on Sketchfab:https://skfb.ly/6xyuR

Fossil Friday - freshwater snail

The world of the dinosaurs was populated by some of the most gargantuan and charismatic animals ever to roam our planet. It is easy to forget that the Mesozoic Era was just as rich with all sorts of life as our modern world. This is the shell of a freshwater snail called Campeloma. This shell was collected by the late Harley Garbani and is part of a collection donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.This Campeloma was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and is about 67 million years old (Late Cretaceous Epoch). While this little snail scooted along the bottom of ponds and streams, the last of the giant dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus andTriceratops, thundered across the land. Living species of Campeloma still inhabit freshwater environments in the United States and Canada.

The world of the dinosaurs was populated by some of the most gargantuan and charismatic animals ever to roam our planet. It is easy to forget that the Mesozoic Era was just as rich with all sorts of life as our modern world. This is the shell of a freshwater snail called Campeloma. This shell was collected by the late Harley Garbani and is part of a collection donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.This Campeloma was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and is about 67 million years old (Late Cretaceous Epoch). While this little snail scooted along the bottom of ponds and streams, the last of the giant dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus andTriceratops, thundered across the land. Living species of Campeloma still inhabit freshwater environments in the United States and Canada.

Fossil Friday -crocodilian teeth

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Fossil Friday - horse lunate

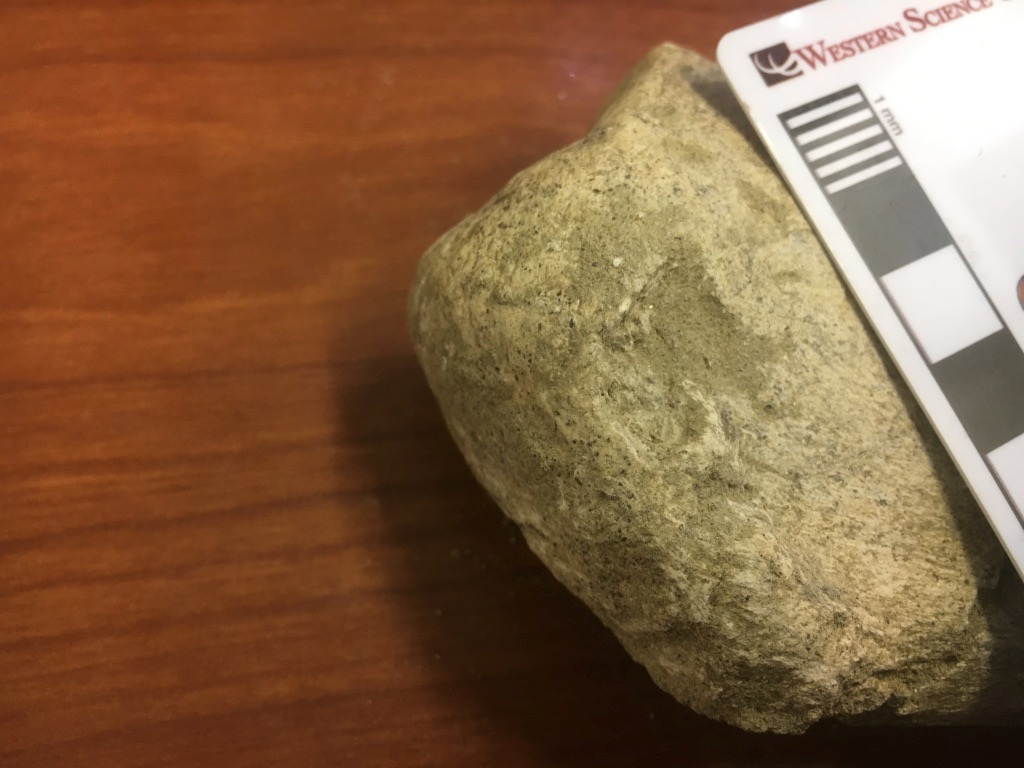

We're continuing our efforts to document an describe the fauna from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, a small but diverse collection that appears to be the only Rancholabrean-Age site in Murrieta. The bone shown here is the left lunate of a horse (Equus sp.), with the original bone on the left and a 3D print on the right. The lunate is one of 6 small bones that form the wrist. In horses they are blocky, tightly interlocking bones that can support the stress of holding the weight of a running horse. Unlike primates, which have highly mobile wrists, the horse wrist has essentially no ability to move side-to-side, as is limited to fore-and-aft motion, making it more stable during running.We're planning to scan and print as many of the Harveston bones as possible. The paint job on this print is too dark, so I need to lighten it a bit. O

We're continuing our efforts to document an describe the fauna from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, a small but diverse collection that appears to be the only Rancholabrean-Age site in Murrieta. The bone shown here is the left lunate of a horse (Equus sp.), with the original bone on the left and a 3D print on the right. The lunate is one of 6 small bones that form the wrist. In horses they are blocky, tightly interlocking bones that can support the stress of holding the weight of a running horse. Unlike primates, which have highly mobile wrists, the horse wrist has essentially no ability to move side-to-side, as is limited to fore-and-aft motion, making it more stable during running.We're planning to scan and print as many of the Harveston bones as possible. The paint job on this print is too dark, so I need to lighten it a bit. O

Fossil Friday - lizard vertebra

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat.

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat. By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Smilodon femur

Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image):

Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image): These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.

These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.

Fossil Friday - ray tooth

We usually think of rays as creatures of the ocean. However, these flattened cartilaginous relatives of sharks also inhabit freshwater, and include the striking freshwater stingrays of South America and the giant freshwater stingrays of southeast Asia. During the Late Cretaceous Epoch, freshwater rays also prowled the waterways of North America. The curious little object shown here is a tooth from one of these Late Cretaceous freshwater rays, called Myledaphus bipartitus. The flat, robust crown of the tooth is towards the top of the picture, and the root towards the bottom. When alive, Myledaphus would have had many such teeth in its jaws, for crushing through its meals of freshwater shellfish.Myledaphus is closely related to the living guitarfish, such as the shovelnose guitarfish Rhinobatos productus (below) that can be found in saltwater off the coast of California:

We usually think of rays as creatures of the ocean. However, these flattened cartilaginous relatives of sharks also inhabit freshwater, and include the striking freshwater stingrays of South America and the giant freshwater stingrays of southeast Asia. During the Late Cretaceous Epoch, freshwater rays also prowled the waterways of North America. The curious little object shown here is a tooth from one of these Late Cretaceous freshwater rays, called Myledaphus bipartitus. The flat, robust crown of the tooth is towards the top of the picture, and the root towards the bottom. When alive, Myledaphus would have had many such teeth in its jaws, for crushing through its meals of freshwater shellfish.Myledaphus is closely related to the living guitarfish, such as the shovelnose guitarfish Rhinobatos productus (below) that can be found in saltwater off the coast of California: The Western Science Center's Myledaphus tooth was collected from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, the same rock layer that has produced fossils of such dinosaurian giants as Tyrannosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops, and an array of other animals that existed 66 million years ago, right before the mass extinction that destroyed all the dinosaurs other than modern birds. Whole skeletons of Myledaphus have been found elsewhere in North America, such as this one featured by the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada (scroll down for image): https://royaltyrrellmuseum.wordpress.com/2016/11/08/everyone-can-do-science/by Andrew McDonald

The Western Science Center's Myledaphus tooth was collected from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, the same rock layer that has produced fossils of such dinosaurian giants as Tyrannosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops, and an array of other animals that existed 66 million years ago, right before the mass extinction that destroyed all the dinosaurs other than modern birds. Whole skeletons of Myledaphus have been found elsewhere in North America, such as this one featured by the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada (scroll down for image): https://royaltyrrellmuseum.wordpress.com/2016/11/08/everyone-can-do-science/by Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - possible Leptoceratops tooth

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - horse mandible

We're continuing our review of our collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. This is a diverse fauna with a number of different genera, but it appears that in terms of shear numbers of bones this collection is dominated by horses.The specimen shown here is a partial lower jaw of Equus occidentalis, including about 2/3 of the right dentary and a fragment of the left dentary at the mandibular symphysis. At the top is the lateral view, with anterior to the right. Below is the medial view, with anterior to the left:

We're continuing our review of our collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. This is a diverse fauna with a number of different genera, but it appears that in terms of shear numbers of bones this collection is dominated by horses.The specimen shown here is a partial lower jaw of Equus occidentalis, including about 2/3 of the right dentary and a fragment of the left dentary at the mandibular symphysis. At the top is the lateral view, with anterior to the right. Below is the medial view, with anterior to the left: And the dorsal view, also with anterior to the left, and showing the occlusal surfaces of the teeth:

And the dorsal view, also with anterior to the left, and showing the occlusal surfaces of the teeth: The entire right dentition except for the incisors is preserved, from the 2nd premolar to the 3rd molar. These are all adult teeth, and they are all in wear, so this was an adult horse. In fact, in the lateral view at the top, we can see the unerupted part of the 3rd premolar. There is only a very short crown present above the root. Horses have teeth with extremely tall crowns, so possibly as much as 70-80% of this tooth has worn away. This horse was not just an adult, but was elderly (or, at least its teeth show an amount of wear typically only seen in elderly horses).

The entire right dentition except for the incisors is preserved, from the 2nd premolar to the 3rd molar. These are all adult teeth, and they are all in wear, so this was an adult horse. In fact, in the lateral view at the top, we can see the unerupted part of the 3rd premolar. There is only a very short crown present above the root. Horses have teeth with extremely tall crowns, so possibly as much as 70-80% of this tooth has worn away. This horse was not just an adult, but was elderly (or, at least its teeth show an amount of wear typically only seen in elderly horses).

Fossil Friday - strange mastodon vertebrae

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however).

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however). The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

Fossil Friday - camel vertebra

This is a cervical (neck) vertebra of a giant extinct camel called Camelops, which roamed southern California during the Pleistocene Epoch, perhaps less than 50,000 years ago. This particular specimen was discovered in 2002 near Murrieta, and is part of a fauna that also includes horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths. The view shown here is the right lateral view of the vertebra, showing the ball-shaped structure and large prongs (prezygapophyses) that would have articulated with the next vertebra closer to the head.

This is a cervical (neck) vertebra of a giant extinct camel called Camelops, which roamed southern California during the Pleistocene Epoch, perhaps less than 50,000 years ago. This particular specimen was discovered in 2002 near Murrieta, and is part of a fauna that also includes horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths. The view shown here is the right lateral view of the vertebra, showing the ball-shaped structure and large prongs (prezygapophyses) that would have articulated with the next vertebra closer to the head.

Fossil Friday - Smilodon vertebra

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

Fossil Friday - crocodile jaw

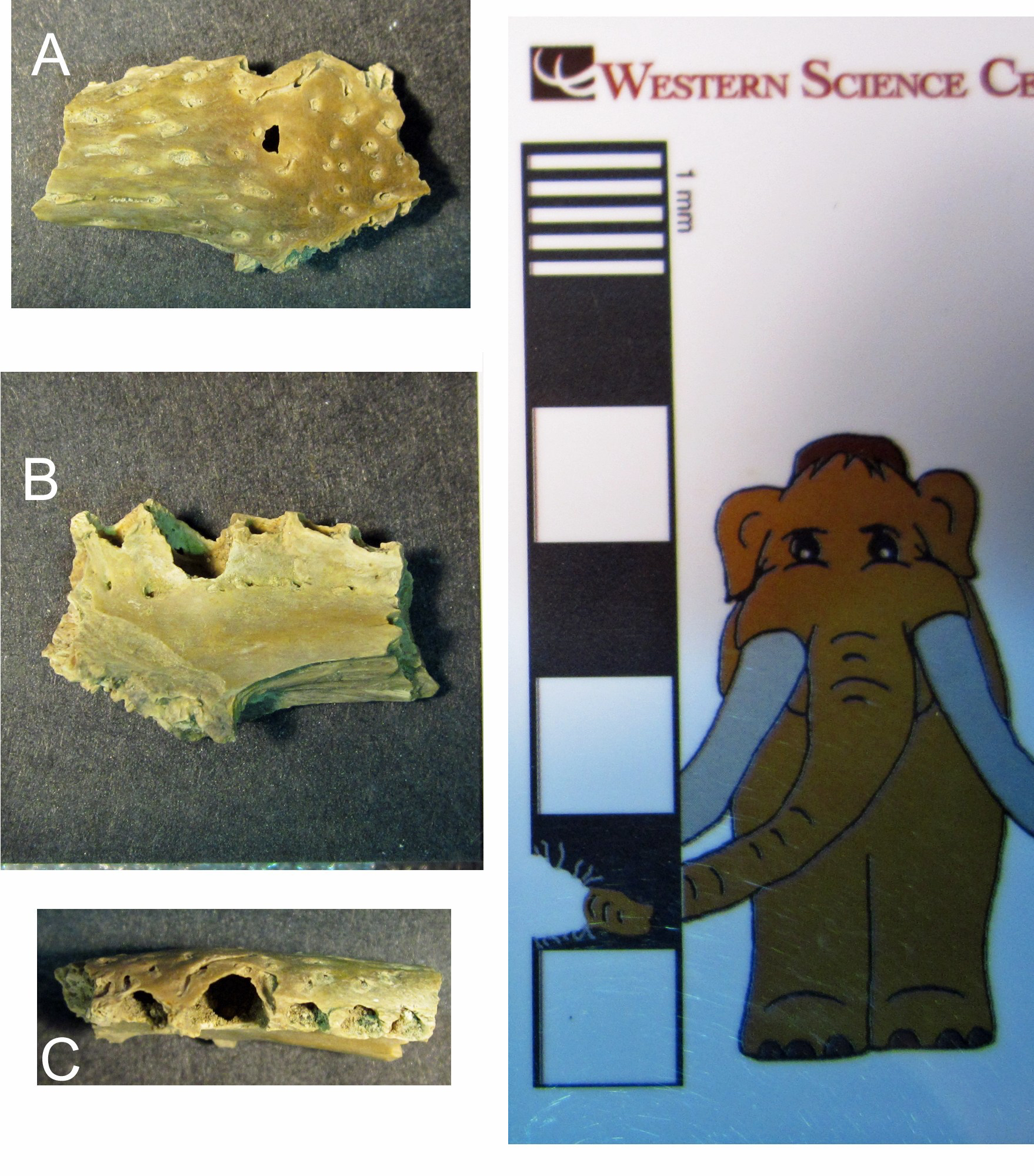

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

Fossil Friday - deer antler

Over the last few weeks we’ve been continuing both our studies of the collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, as well as setting up and learning to use our new 3D scanning and printing capabilities. These two projects have rapidly started to come together. The specimen on the right is an antler from a small deer, consistent in size and shape with the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus (that’s been the case with all our deer material from Harveston so far). Given the way this antler is preserved, it’s likely that it was a shed antler.On the left is a 3D print of the same antler. We’ve now printed out several fossils at WSC, but what makes this one unique is that it’s the first print based on a 3D image file that we produced in-house. Rather than being produced with a laser scanner, this file was generated using photogrammetry, using 70 different photos of the antler. We’re planning to use both laser scanning and photogrammetry to generate our 3D models.The model of the deer antler is available for viewing or download on Sketchfab.

Over the last few weeks we’ve been continuing both our studies of the collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, as well as setting up and learning to use our new 3D scanning and printing capabilities. These two projects have rapidly started to come together. The specimen on the right is an antler from a small deer, consistent in size and shape with the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus (that’s been the case with all our deer material from Harveston so far). Given the way this antler is preserved, it’s likely that it was a shed antler.On the left is a 3D print of the same antler. We’ve now printed out several fossils at WSC, but what makes this one unique is that it’s the first print based on a 3D image file that we produced in-house. Rather than being produced with a laser scanner, this file was generated using photogrammetry, using 70 different photos of the antler. We’re planning to use both laser scanning and photogrammetry to generate our 3D models.The model of the deer antler is available for viewing or download on Sketchfab.