We usually think of rays as creatures of the ocean. However, these flattened cartilaginous relatives of sharks also inhabit freshwater, and include the striking freshwater stingrays of South America and the giant freshwater stingrays of southeast Asia. During the Late Cretaceous Epoch, freshwater rays also prowled the waterways of North America. The curious little object shown here is a tooth from one of these Late Cretaceous freshwater rays, called Myledaphus bipartitus. The flat, robust crown of the tooth is towards the top of the picture, and the root towards the bottom. When alive, Myledaphus would have had many such teeth in its jaws, for crushing through its meals of freshwater shellfish.Myledaphus is closely related to the living guitarfish, such as the shovelnose guitarfish Rhinobatos productus (below) that can be found in saltwater off the coast of California:

We usually think of rays as creatures of the ocean. However, these flattened cartilaginous relatives of sharks also inhabit freshwater, and include the striking freshwater stingrays of South America and the giant freshwater stingrays of southeast Asia. During the Late Cretaceous Epoch, freshwater rays also prowled the waterways of North America. The curious little object shown here is a tooth from one of these Late Cretaceous freshwater rays, called Myledaphus bipartitus. The flat, robust crown of the tooth is towards the top of the picture, and the root towards the bottom. When alive, Myledaphus would have had many such teeth in its jaws, for crushing through its meals of freshwater shellfish.Myledaphus is closely related to the living guitarfish, such as the shovelnose guitarfish Rhinobatos productus (below) that can be found in saltwater off the coast of California: The Western Science Center's Myledaphus tooth was collected from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, the same rock layer that has produced fossils of such dinosaurian giants as Tyrannosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops, and an array of other animals that existed 66 million years ago, right before the mass extinction that destroyed all the dinosaurs other than modern birds. Whole skeletons of Myledaphus have been found elsewhere in North America, such as this one featured by the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada (scroll down for image): https://royaltyrrellmuseum.wordpress.com/2016/11/08/everyone-can-do-science/by Andrew McDonald

The Western Science Center's Myledaphus tooth was collected from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, the same rock layer that has produced fossils of such dinosaurian giants as Tyrannosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops, and an array of other animals that existed 66 million years ago, right before the mass extinction that destroyed all the dinosaurs other than modern birds. Whole skeletons of Myledaphus have been found elsewhere in North America, such as this one featured by the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada (scroll down for image): https://royaltyrrellmuseum.wordpress.com/2016/11/08/everyone-can-do-science/by Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - possible Leptoceratops tooth

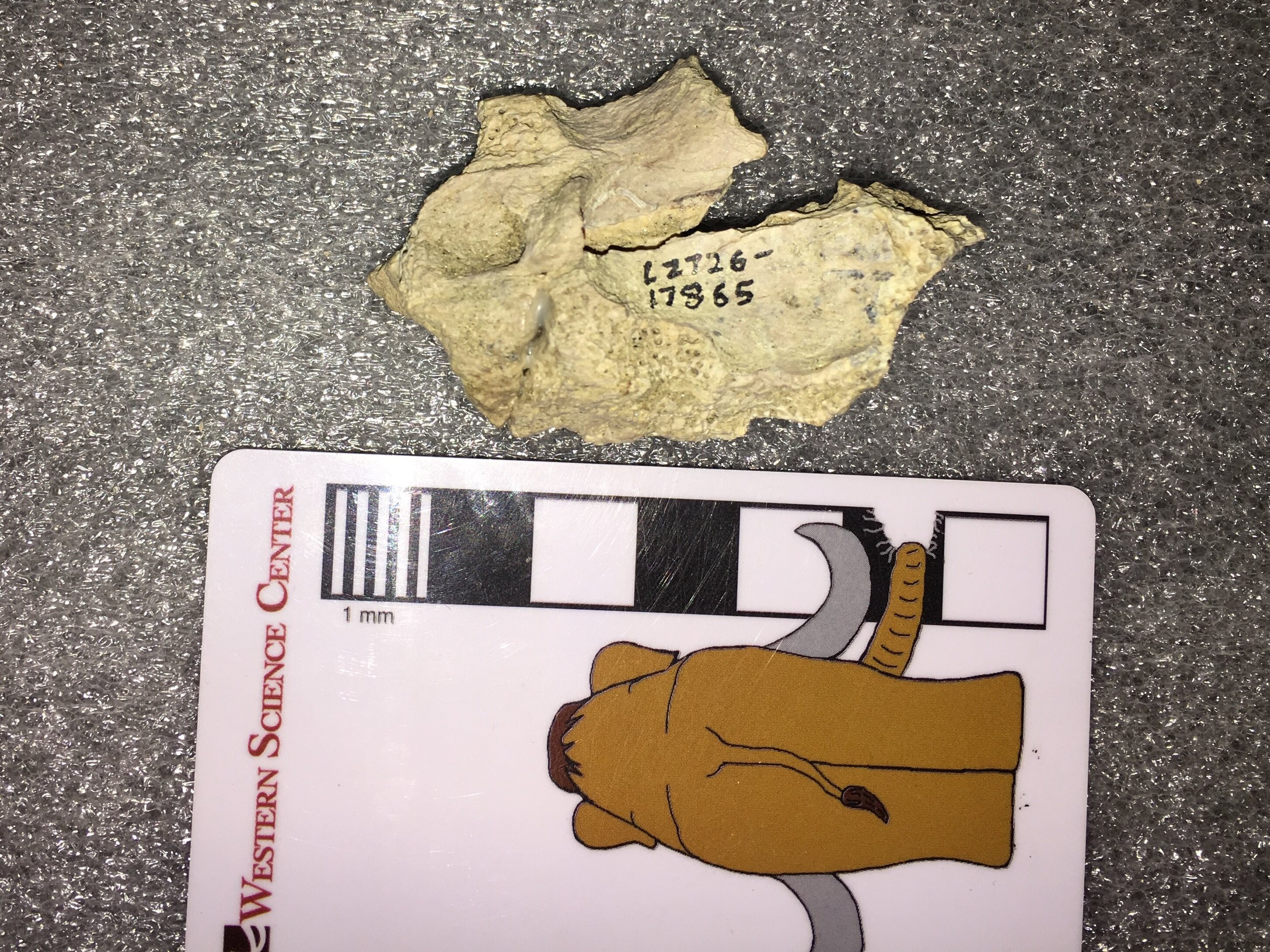

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - horse mandible

We're continuing our review of our collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. This is a diverse fauna with a number of different genera, but it appears that in terms of shear numbers of bones this collection is dominated by horses.The specimen shown here is a partial lower jaw of Equus occidentalis, including about 2/3 of the right dentary and a fragment of the left dentary at the mandibular symphysis. At the top is the lateral view, with anterior to the right. Below is the medial view, with anterior to the left:

We're continuing our review of our collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. This is a diverse fauna with a number of different genera, but it appears that in terms of shear numbers of bones this collection is dominated by horses.The specimen shown here is a partial lower jaw of Equus occidentalis, including about 2/3 of the right dentary and a fragment of the left dentary at the mandibular symphysis. At the top is the lateral view, with anterior to the right. Below is the medial view, with anterior to the left: And the dorsal view, also with anterior to the left, and showing the occlusal surfaces of the teeth:

And the dorsal view, also with anterior to the left, and showing the occlusal surfaces of the teeth: The entire right dentition except for the incisors is preserved, from the 2nd premolar to the 3rd molar. These are all adult teeth, and they are all in wear, so this was an adult horse. In fact, in the lateral view at the top, we can see the unerupted part of the 3rd premolar. There is only a very short crown present above the root. Horses have teeth with extremely tall crowns, so possibly as much as 70-80% of this tooth has worn away. This horse was not just an adult, but was elderly (or, at least its teeth show an amount of wear typically only seen in elderly horses).

The entire right dentition except for the incisors is preserved, from the 2nd premolar to the 3rd molar. These are all adult teeth, and they are all in wear, so this was an adult horse. In fact, in the lateral view at the top, we can see the unerupted part of the 3rd premolar. There is only a very short crown present above the root. Horses have teeth with extremely tall crowns, so possibly as much as 70-80% of this tooth has worn away. This horse was not just an adult, but was elderly (or, at least its teeth show an amount of wear typically only seen in elderly horses).

Fossil Friday - strange mastodon vertebrae

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however).

A lot of the work done by paleontologists and biologists, especially those that work on taxonomy and systematics, is trying to identify general characteristics that various groups of animals have in common and that differ in other groups. The characters are the raw material that we use to define and identify species, to unravel the evolutionary relationships between those species and group them into higher taxa, and to identify sexes, ages, and other features. But, of course, the smallest unit we deal with is the individual animal, and sometimes fossils are emphatically, stubbornly individualistic.The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has given us a chance to pull lots of mastodon remains out and compare them more easily, which makes some of the individual characteristics more visible. One interesting specimen that is going to merit a close look at some point is a series of relatively small associated neck and back vertebrae. These vertebrae are not associated with teeth or tusks, but their morphology is well within the range for mastodons, if on the small side (I have seen smaller, however). The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

The unusual thing about these vertebrae is the texture of the bone, particularly the vertebral centra, as can be seen in the 5th vertebra (above). This bone has a strange, lightweight texture that I haven't seen before; it almost looks like strips of bone woven together. It seems to be concentrated on the centra, and seems to present to some degree on all of the vertebrae for which the centrum is preserved.I'm not sure what this is. Could it be some type of taphonomic damage, caused by weathering, or maybe being eaten by insects? Maybe, although the fact that it's found only on the centra but on all the centra makes this less likely. Or could it be some type of bone disease, some type of cancer or osteoporosis-like condition? I lean toward this explanation, but at this point I'm not really very confident in that answer either.If you want to look at the bones yourself and make your own guess, the vertebrae are in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit until this May.

Fossil Friday - camel vertebra

This is a cervical (neck) vertebra of a giant extinct camel called Camelops, which roamed southern California during the Pleistocene Epoch, perhaps less than 50,000 years ago. This particular specimen was discovered in 2002 near Murrieta, and is part of a fauna that also includes horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths. The view shown here is the right lateral view of the vertebra, showing the ball-shaped structure and large prongs (prezygapophyses) that would have articulated with the next vertebra closer to the head.

This is a cervical (neck) vertebra of a giant extinct camel called Camelops, which roamed southern California during the Pleistocene Epoch, perhaps less than 50,000 years ago. This particular specimen was discovered in 2002 near Murrieta, and is part of a fauna that also includes horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths. The view shown here is the right lateral view of the vertebra, showing the ball-shaped structure and large prongs (prezygapophyses) that would have articulated with the next vertebra closer to the head.

Fossil Friday - Smilodon vertebra

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

The amazing deposits at Rancho La Brea portray a biased view of California's Ice Age fauna. The vast numbers of sabertooth cats, dire wolves, and other carnivores are impressive to see and have provided a bonanza of scientific studies over the years, but they give the impression that the Ice Age was overrun by predators. In fact, in most deposits herbivores are much more common and predators are scarce, just as in modern healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, occasional carnivores do show up in these deposits. The early Pleistocene deposits in San Timoteo Canyon, near Redlands CA, are dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of deer, sloths, and camels. But among the 16,000 specimens from the site in the WSC collections, there are associated remains of two large carnivores, including a sabertooth cat.Above is a dorsal view of the 12th thoracic vertebra of Smilodon gracilis. S. gracilis is thought to be ancestral to the younger S. fatalis of Rancho La Brea, and was smaller and more lightly built than its better known and more famous descendant. Lateral and anterior views are shown below:

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

There are numerous S. gracilis bones from this site, which all appear to come from a single individual. Unfortunately, all the preserved elements are postcranial bones, with no cranial bones or teeth. Nevertheless, these represent significant remains of a relatively rare carnivore. We had several of these bones out this week for 3D scanning, and those scans will be made public sometime next year.

Fossil Friday - crocodile jaw

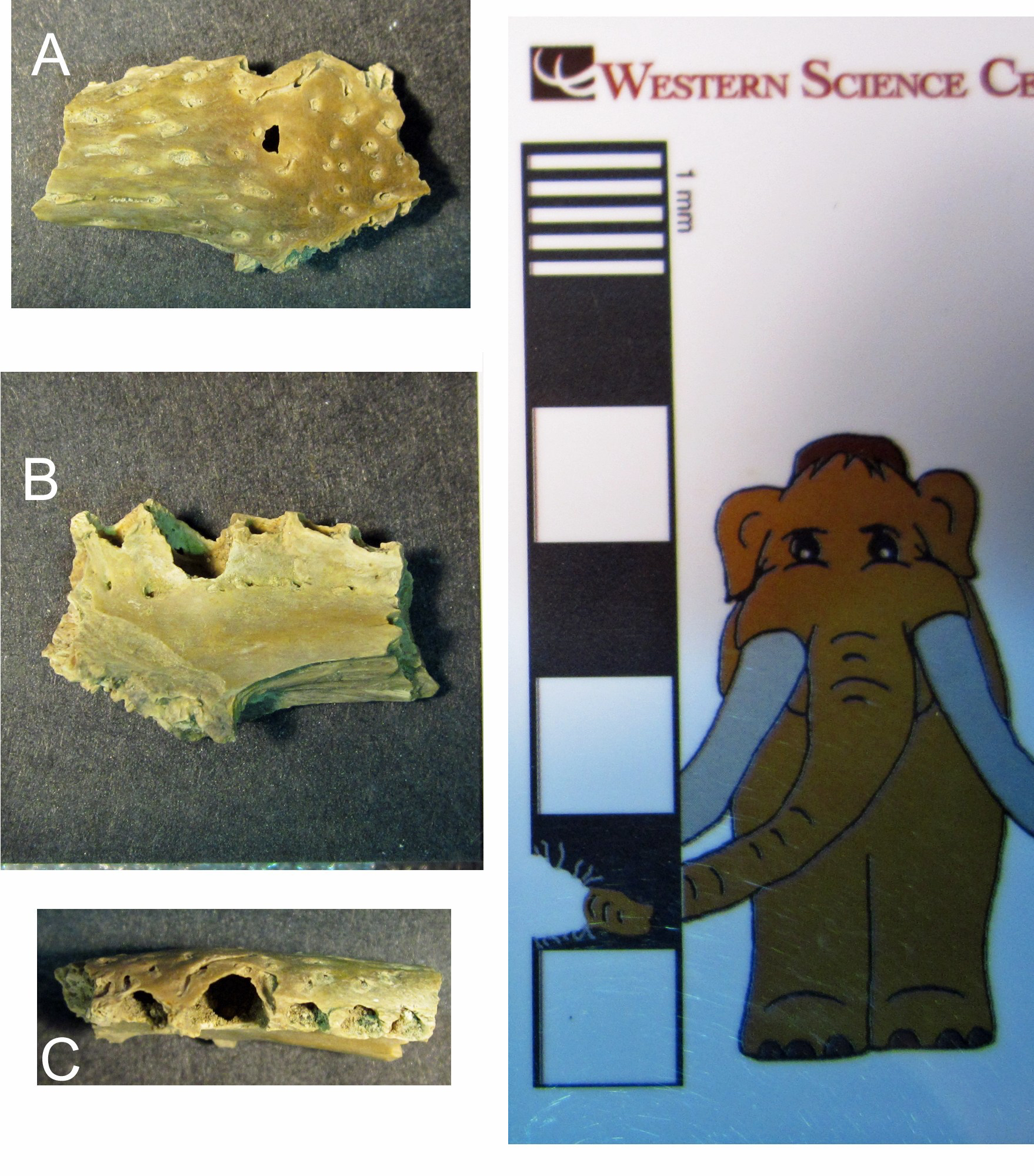

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

Fossil Friday - deer antler

Over the last few weeks we’ve been continuing both our studies of the collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, as well as setting up and learning to use our new 3D scanning and printing capabilities. These two projects have rapidly started to come together. The specimen on the right is an antler from a small deer, consistent in size and shape with the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus (that’s been the case with all our deer material from Harveston so far). Given the way this antler is preserved, it’s likely that it was a shed antler.On the left is a 3D print of the same antler. We’ve now printed out several fossils at WSC, but what makes this one unique is that it’s the first print based on a 3D image file that we produced in-house. Rather than being produced with a laser scanner, this file was generated using photogrammetry, using 70 different photos of the antler. We’re planning to use both laser scanning and photogrammetry to generate our 3D models.The model of the deer antler is available for viewing or download on Sketchfab.

Over the last few weeks we’ve been continuing both our studies of the collection of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, as well as setting up and learning to use our new 3D scanning and printing capabilities. These two projects have rapidly started to come together. The specimen on the right is an antler from a small deer, consistent in size and shape with the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus (that’s been the case with all our deer material from Harveston so far). Given the way this antler is preserved, it’s likely that it was a shed antler.On the left is a 3D print of the same antler. We’ve now printed out several fossils at WSC, but what makes this one unique is that it’s the first print based on a 3D image file that we produced in-house. Rather than being produced with a laser scanner, this file was generated using photogrammetry, using 70 different photos of the antler. We’re planning to use both laser scanning and photogrammetry to generate our 3D models.The model of the deer antler is available for viewing or download on Sketchfab.

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian rib

A few months ago Dr. Andrew McDonal joined the staff of WSC as our new curator. Andrew has been excavating for several years in the Cretaceous Menefee Formation on federal land in New Mexico, and now some of that material is making its way to WSC. This morning we opened our first Menefee Formation field jacket on public view at the museum’s Exploration Station. The image above shows the jacket after about 3 hours of prep work. The jacket contains a ceratopsian rib, the posterior edge of which is visible running through the middle of the jacket from the left end to about 10 cm past the top of the scale bar. The rib actually continues all the way to the other end of the jacket, but we’ve not yet uncovered it that far. The small black specks dotting the sediment are fragments of charcoal from burned Cretaceous trees.Andrew tells me that this rib is part of an associated skeleton including at least a dozen bones, from a small, probably juvenile, ceratopsian. So far we don’t know what taxon it represents, but there’s still a lot of material to prepare. This rib will be on public view in the Exploration Station for the next few weeks as we continue our preparation work.

A few months ago Dr. Andrew McDonal joined the staff of WSC as our new curator. Andrew has been excavating for several years in the Cretaceous Menefee Formation on federal land in New Mexico, and now some of that material is making its way to WSC. This morning we opened our first Menefee Formation field jacket on public view at the museum’s Exploration Station. The image above shows the jacket after about 3 hours of prep work. The jacket contains a ceratopsian rib, the posterior edge of which is visible running through the middle of the jacket from the left end to about 10 cm past the top of the scale bar. The rib actually continues all the way to the other end of the jacket, but we’ve not yet uncovered it that far. The small black specks dotting the sediment are fragments of charcoal from burned Cretaceous trees.Andrew tells me that this rib is part of an associated skeleton including at least a dozen bones, from a small, probably juvenile, ceratopsian. So far we don’t know what taxon it represents, but there’s still a lot of material to prepare. This rib will be on public view in the Exploration Station for the next few weeks as we continue our preparation work.

Fossil Friday - printed bison calcaneum

At our annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser last September, or donors provided us with funding to start a #D scanning and printing lab the the Western Science Center. While some of our equipment is still on order, our first printer arrived a few weeks ago and we've been printing as much as possible while we train ourselves in its use. During the Valley of the Mastodons Symposium, Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Lab scanned a number of our specimens. While we wait for our scanner to arrive we've been printing some of Bernard's scans.Earlier this week we printed a right Bison calcaneum, seen above in medial view. The original specimen is exhibited in the floor case with the mastodon "Little Stevie" (they were found together). It's difficult to photograph through this case (below), and it's difficult to open; the symposium is the first time it has been opened in 11 years! So while the case was opened we scanned as much as possible, including this calcaneum (which is visible in the center of the case photo below):

At our annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser last September, or donors provided us with funding to start a #D scanning and printing lab the the Western Science Center. While some of our equipment is still on order, our first printer arrived a few weeks ago and we've been printing as much as possible while we train ourselves in its use. During the Valley of the Mastodons Symposium, Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Lab scanned a number of our specimens. While we wait for our scanner to arrive we've been printing some of Bernard's scans.Earlier this week we printed a right Bison calcaneum, seen above in medial view. The original specimen is exhibited in the floor case with the mastodon "Little Stevie" (they were found together). It's difficult to photograph through this case (below), and it's difficult to open; the symposium is the first time it has been opened in 11 years! So while the case was opened we scanned as much as possible, including this calcaneum (which is visible in the center of the case photo below): This bone was our largest single print to date, and took about 24 hours to print. We've since printed a slightly larger bone as we continue to explore the limits of the printer.

This bone was our largest single print to date, and took about 24 hours to print. We've since printed a slightly larger bone as we continue to explore the limits of the printer. The calcaneum is part of the foot and ankle structure, and forms the heel and the attachment point for the Achilles tendon. This particular specimen was collected at Diamond Valley Lake's East Dam, and is roughly 45,000 years old. The original specimen is now back on display in its floor case, while the printed replica will be added to our teaching collection.

The calcaneum is part of the foot and ankle structure, and forms the heel and the attachment point for the Achilles tendon. This particular specimen was collected at Diamond Valley Lake's East Dam, and is roughly 45,000 years old. The original specimen is now back on display in its floor case, while the printed replica will be added to our teaching collection.

Fossil Friday - deer humerus

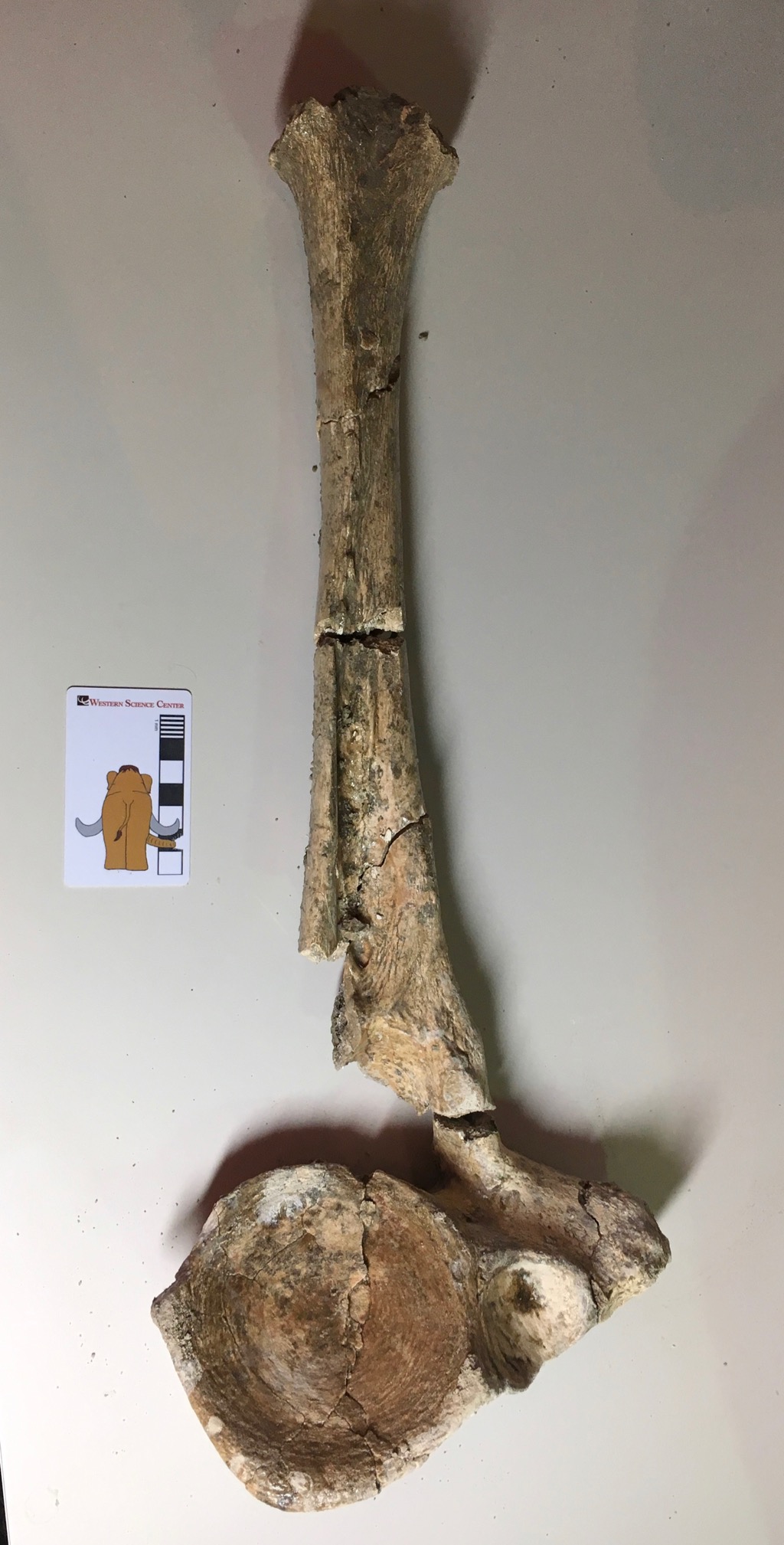

One of the collections at WSC comes from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta in Riverside County. While this is a fairly small collection, it’s amazingly diverse, with well over a dozen different species of mammals. A group of us have started going through this collection to document it. One of the Harveston specimens is a small deer, probably the genus Odocoileus. The element above is the distal end of the humerus. Modern Odocoileus includes the mule deer O. hemionius and the smaller white-tailed deer O. virginianus. Interestingly, the Harveston specimen is quite a bit smaller than modern white-tailed deer, even though it’s an adult. We have a few other deer elements from the Harveston material that we’ll have to compare to see if the size difference is consistent.

One of the collections at WSC comes from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta in Riverside County. While this is a fairly small collection, it’s amazingly diverse, with well over a dozen different species of mammals. A group of us have started going through this collection to document it. One of the Harveston specimens is a small deer, probably the genus Odocoileus. The element above is the distal end of the humerus. Modern Odocoileus includes the mule deer O. hemionius and the smaller white-tailed deer O. virginianus. Interestingly, the Harveston specimen is quite a bit smaller than modern white-tailed deer, even though it’s an adult. We have a few other deer elements from the Harveston material that we’ll have to compare to see if the size difference is consistent.

Fossil Friday - vacation!

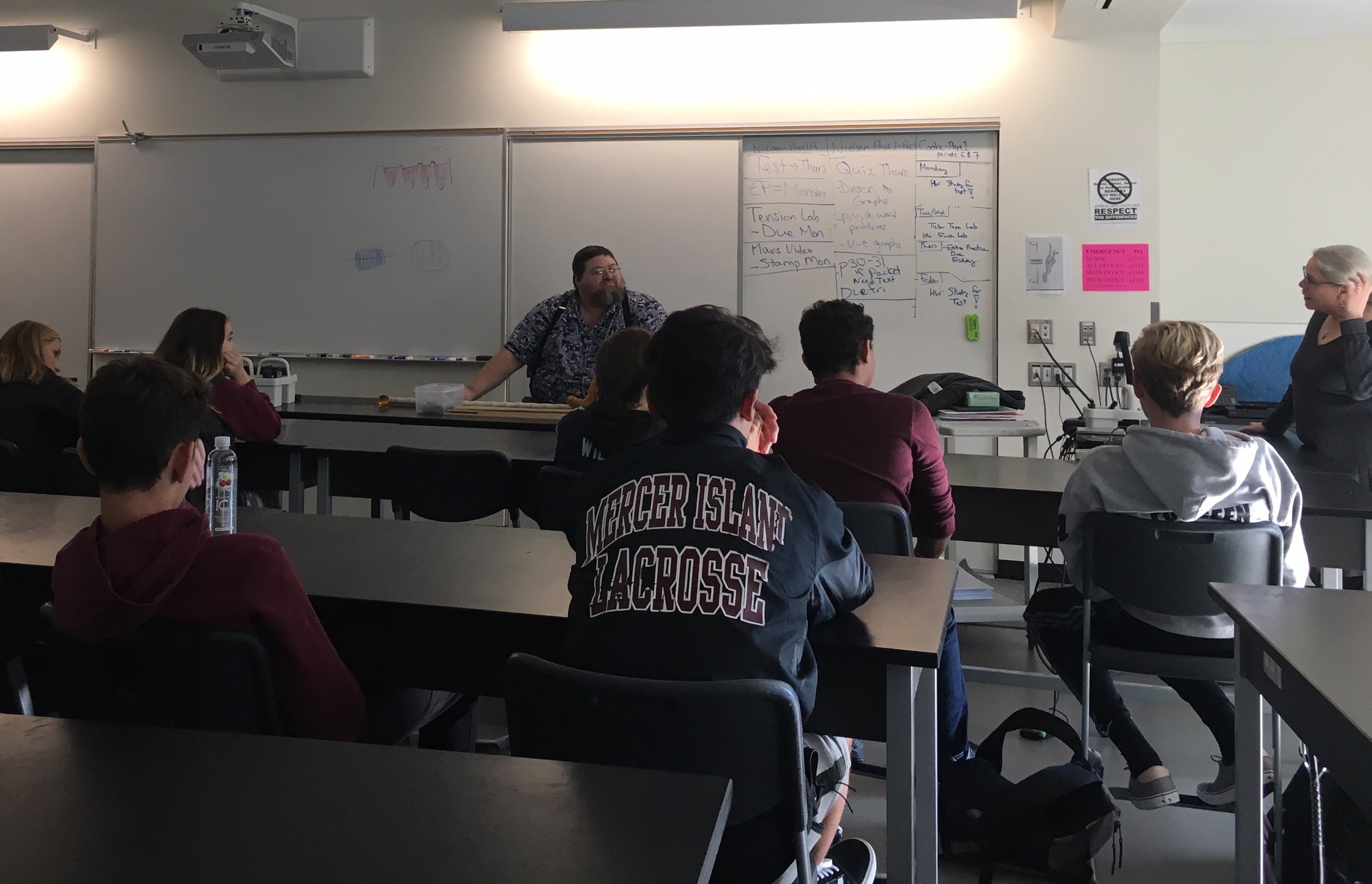

For the past week Brett and I have been in Seattle attending the 2017 meeting of the Geological Society of America, where we were presenting on the “Stepping out of the Past” and “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits. The meeting ended Wednesday night, and we’re now taking a short vacation to see geological sites in the northwest. But today things took a slight detour. While at the conference, we ran into an old friend, Patty Weston. Patty, Brett, and I were all geology majors together at Carleton College, but I had last seen her when Brett and I got married 23 years ago (although we still corresponding Facebook). She now teaches science at Mercer Island High School outside Seattle. One evening at the conference as we were discussing plans we realized that today on our way to some geological sites we would be driving within a few minutes of her school, so she invited us to stop by and talk to her class about mastodons. We said we’d love to, but since we were on vacation I didn’t have any of the cast teeth or other props I’d usually use to give such a talk. Then it occurred to me: during the “Valley of the Mastodons” Symposium Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Laboratory scanned a bunch of our mastodon teeth. So I showed Patty the files and told her that, if the school has access to a 3D printer, they could print one of the teeth and I could talk about that on Friday. And so it happened that this morning I was talked to a group of 9th graders in Washington about a tooth from my museum in California, using a 3D file produced by a lab in Virginia and printed out 12 hours earlier.

For the past week Brett and I have been in Seattle attending the 2017 meeting of the Geological Society of America, where we were presenting on the “Stepping out of the Past” and “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits. The meeting ended Wednesday night, and we’re now taking a short vacation to see geological sites in the northwest. But today things took a slight detour. While at the conference, we ran into an old friend, Patty Weston. Patty, Brett, and I were all geology majors together at Carleton College, but I had last seen her when Brett and I got married 23 years ago (although we still corresponding Facebook). She now teaches science at Mercer Island High School outside Seattle. One evening at the conference as we were discussing plans we realized that today on our way to some geological sites we would be driving within a few minutes of her school, so she invited us to stop by and talk to her class about mastodons. We said we’d love to, but since we were on vacation I didn’t have any of the cast teeth or other props I’d usually use to give such a talk. Then it occurred to me: during the “Valley of the Mastodons” Symposium Bernard Means from the Virtual Curation Laboratory scanned a bunch of our mastodon teeth. So I showed Patty the files and told her that, if the school has access to a 3D printer, they could print one of the teeth and I could talk about that on Friday. And so it happened that this morning I was talked to a group of 9th graders in Washington about a tooth from my museum in California, using a 3D file produced by a lab in Virginia and printed out 12 hours earlier.

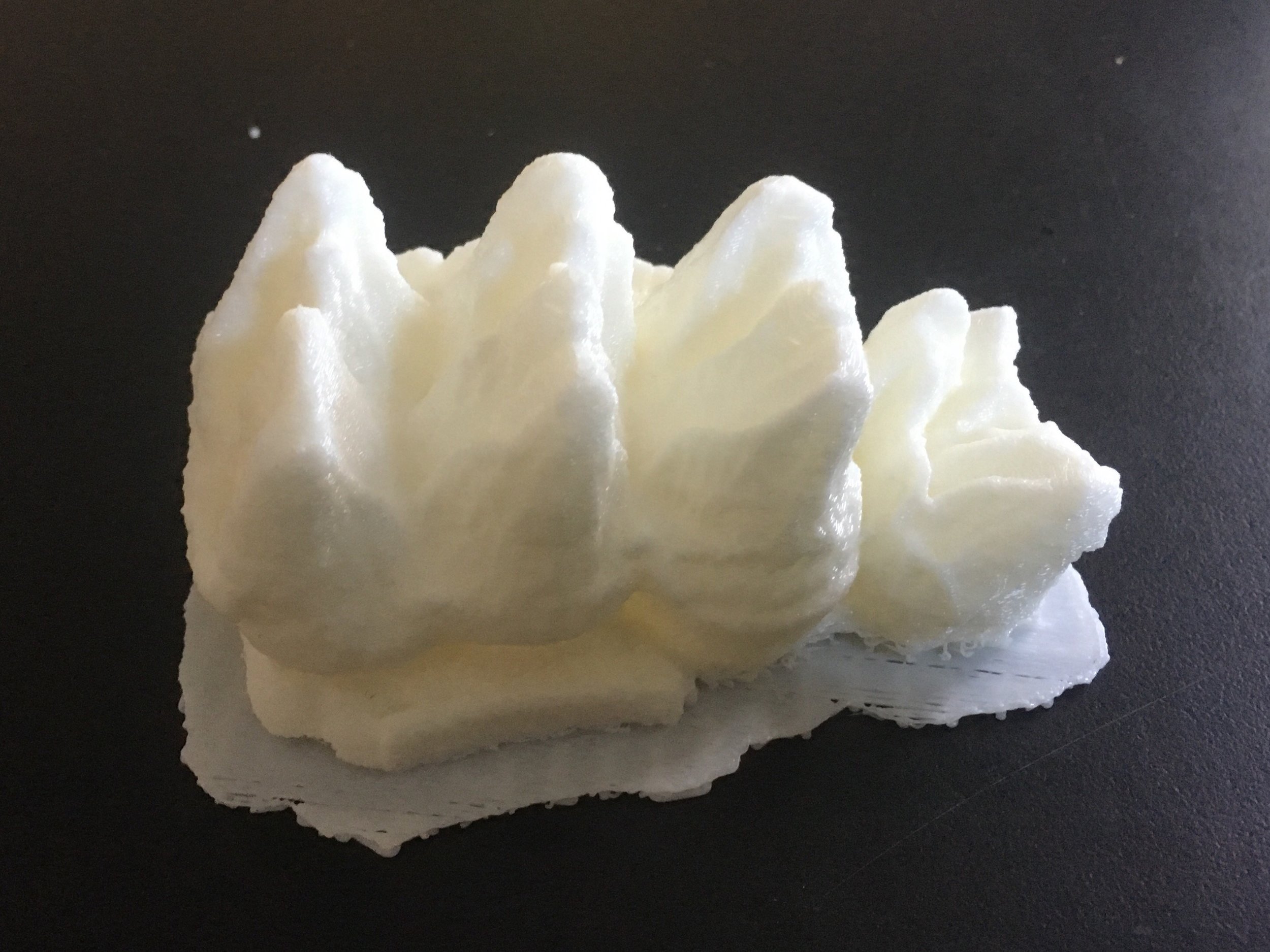

The tooth they printed, seen at the top and below, with Max, is an unerupted upper 4th premolar and the posterior part of the 3rd premolar from Diamond Valley Lake. This is the youngest mastodon (in terms of the animal’s age at death) in the WSC collection; we estimate it was between 2 and 6 months old when it died. The original specimen is currently on display in the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibit.

The tooth they printed, seen at the top and below, with Max, is an unerupted upper 4th premolar and the posterior part of the 3rd premolar from Diamond Valley Lake. This is the youngest mastodon (in terms of the animal’s age at death) in the WSC collection; we estimate it was between 2 and 6 months old when it died. The original specimen is currently on display in the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibit. In the last 2 months WSC has jumped into 3D technology in a big way, recently installing our first printer and with more equipment to come. Today’s visit really made clearer to me the power this technology offers. Thanks to Patty Weston and Mercer Island High School for making this happen, and of course to Bernard and our Science Under the Stars donors who have made this available to WSC.

In the last 2 months WSC has jumped into 3D technology in a big way, recently installing our first printer and with more equipment to come. Today’s visit really made clearer to me the power this technology offers. Thanks to Patty Weston and Mercer Island High School for making this happen, and of course to Bernard and our Science Under the Stars donors who have made this available to WSC.

Fossil Friday - printed mastodon molar

Each September, Western Science Center holds an annual fundraiser called Science Under the Stars to raise funds for museum operations. At the end of the evening we often do a final “Special Ask” to raise dedicated funds for a particular project. This year, for the Special Ask we requested funds for a 3D-scanning, photogrammetry, and printing lab. Our donors, led by the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians, came through in spectacular fashion.

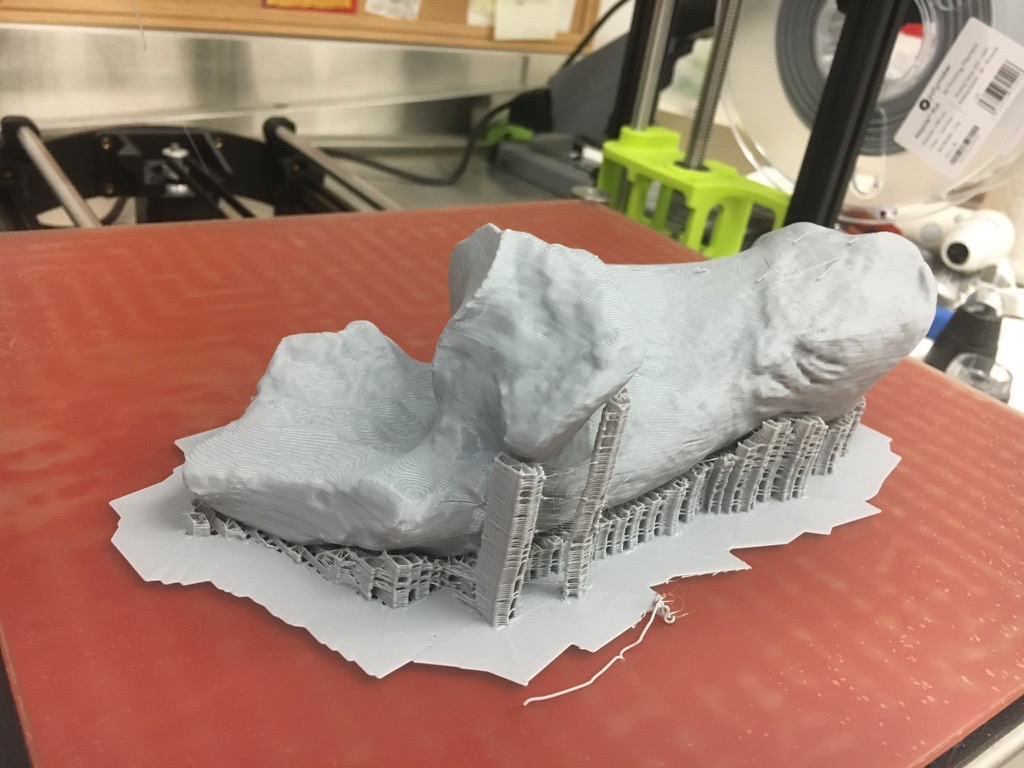

Each September, Western Science Center holds an annual fundraiser called Science Under the Stars to raise funds for museum operations. At the end of the evening we often do a final “Special Ask” to raise dedicated funds for a particular project. This year, for the Special Ask we requested funds for a 3D-scanning, photogrammetry, and printing lab. Our donors, led by the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians, came through in spectacular fashion.  Our first purchase for the lab, a LulzBot TAZ6 printer (above), arrived last week. After our initial demo print to make sure everything was working, our first specimen print was a mastodon tooth (of course). It was printed from a digitial file provided to us by VCU’s Virtual Curation Lab, courtesy of Bernard Means and Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt, which was in turn based on CT scans provided by California Imaging and Diagnostics. The particular tooth is the lower right 3rd molar of a West Dam mastodon we refer to as The Outlier, so named because its 3rd molars are the widest ones known from California (although still narrower than the average m3 from the rest of the country).In a few weeks we’ll be purchasing our scanning and photogrammetry equipment, as well as additional printers, so you’ll be hearing a lot more about this in the months ahead. Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America meeting, where Brett and I will be presenting on both the “Stepping Out of the Past” and the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits, and I’ll have updates from there as well.

Our first purchase for the lab, a LulzBot TAZ6 printer (above), arrived last week. After our initial demo print to make sure everything was working, our first specimen print was a mastodon tooth (of course). It was printed from a digitial file provided to us by VCU’s Virtual Curation Lab, courtesy of Bernard Means and Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt, which was in turn based on CT scans provided by California Imaging and Diagnostics. The particular tooth is the lower right 3rd molar of a West Dam mastodon we refer to as The Outlier, so named because its 3rd molars are the widest ones known from California (although still narrower than the average m3 from the rest of the country).In a few weeks we’ll be purchasing our scanning and photogrammetry equipment, as well as additional printers, so you’ll be hearing a lot more about this in the months ahead. Next week I’m attending the Geological Society of America meeting, where Brett and I will be presenting on both the “Stepping Out of the Past” and the “Valley of the Mastodons” exhibits, and I’ll have updates from there as well.

Fossil Friday - vole tooth

This week is National Rodent Awareness Week. Fossil rodents may not get a lot of headlines, but they are often the most common vertebrate fossils in Neogene terrestrial deposits, and have the potential to convey huge amounts of information about age and paleoenvironment.One of the larger collections at the Western Science Center is from the Southern California Edison El Casco substation in Riverside County. These Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene deposits of the San Timoteo Formation produced over 16,000 fossils, including large numbers of rodents.Shown above is the right lower first molar of Microtus, a vole. It's shown in medial view, with anterior to the left. The black and white bands under the tooth are each 1 mm thick, so the whole tooth is about 4 mm tall.Voles and other members of the subfamily Arvicolinae (including hamsters, lemmings, and muskrats) are herbivores, and often eat abrasive food such as grasses. Like many other herbivores, this is reflected in their tooth anatomy, which includes loops of enamel with exposed dentine in the middle. Because the enamel is harder than the dentine, it always sticks up a bit higher than the dentine and allows the tooth to stay sharp even as it wears down. The enamel loops are expressed as ridges or columns when seen from the side, and are clearly visible in the view above. In occlusal view (below), the loops are expressed as a series of alternating triangles, a pattern that is characteristic of the arvicolines.

This week is National Rodent Awareness Week. Fossil rodents may not get a lot of headlines, but they are often the most common vertebrate fossils in Neogene terrestrial deposits, and have the potential to convey huge amounts of information about age and paleoenvironment.One of the larger collections at the Western Science Center is from the Southern California Edison El Casco substation in Riverside County. These Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene deposits of the San Timoteo Formation produced over 16,000 fossils, including large numbers of rodents.Shown above is the right lower first molar of Microtus, a vole. It's shown in medial view, with anterior to the left. The black and white bands under the tooth are each 1 mm thick, so the whole tooth is about 4 mm tall.Voles and other members of the subfamily Arvicolinae (including hamsters, lemmings, and muskrats) are herbivores, and often eat abrasive food such as grasses. Like many other herbivores, this is reflected in their tooth anatomy, which includes loops of enamel with exposed dentine in the middle. Because the enamel is harder than the dentine, it always sticks up a bit higher than the dentine and allows the tooth to stay sharp even as it wears down. The enamel loops are expressed as ridges or columns when seen from the side, and are clearly visible in the view above. In occlusal view (below), the loops are expressed as a series of alternating triangles, a pattern that is characteristic of the arvicolines.

Fossil Friday - cat skull fragments

With many fossils, particularly vertebrates, small fragments can sometimes be very informative and justify close scrutiny. That was the case with a pair of associated bones from Diamond Valley Lake. One of the fragments, shown above, includes the occipital condyles that form the articulation between the skull and the first vertebra. The condyles sit on either side of the foramen magnum, the opening through which the spinal cord passes.The second fragment, below, appears to be part of the bottom of the skull just anterior to the condyles, including portions of the left squamosal and basisphenoid.

With many fossils, particularly vertebrates, small fragments can sometimes be very informative and justify close scrutiny. That was the case with a pair of associated bones from Diamond Valley Lake. One of the fragments, shown above, includes the occipital condyles that form the articulation between the skull and the first vertebra. The condyles sit on either side of the foramen magnum, the opening through which the spinal cord passes.The second fragment, below, appears to be part of the bottom of the skull just anterior to the condyles, including portions of the left squamosal and basisphenoid.  The initial DVL report identified these fragments as coming from a cat, but the type of cat was uncertain. They appear to be far too large to come from a mountain lion, and the report suggests they may be from a jaguar, Panthera onca. Today jaguars are only found in South America and as far north as Mexico (except for one individual roaming the mountains near Tucson, Arizona), but the species originated in North America and was widespread in the southern US states during the Pleistocene. However, as pointed out in the DVL report, it was very rare in the Pleistocene of Southern California and would be a surprising find at Diamond Valley Lake. We have a cast jaguar skull in our teaching collection that allows for comparison:

The initial DVL report identified these fragments as coming from a cat, but the type of cat was uncertain. They appear to be far too large to come from a mountain lion, and the report suggests they may be from a jaguar, Panthera onca. Today jaguars are only found in South America and as far north as Mexico (except for one individual roaming the mountains near Tucson, Arizona), but the species originated in North America and was widespread in the southern US states during the Pleistocene. However, as pointed out in the DVL report, it was very rare in the Pleistocene of Southern California and would be a surprising find at Diamond Valley Lake. We have a cast jaguar skull in our teaching collection that allows for comparison: The DVL specimen is much larger than the modern cast, but that's not a problem; Pleistocene jaguars were larger than modern ones. The shape is somewhat similar, but there are differences in the shape of the condyles. In an oblique ventral view (below) it's also clear that the basioccipital (the bone just in front of the condyles) is shaped quite differently:

The DVL specimen is much larger than the modern cast, but that's not a problem; Pleistocene jaguars were larger than modern ones. The shape is somewhat similar, but there are differences in the shape of the condyles. In an oblique ventral view (below) it's also clear that the basioccipital (the bone just in front of the condyles) is shaped quite differently: As it turns out, this fragment is a pretty close (if not perfect) match in size and shape for our cast of Smilodon from Rancholabrean La Brea:

As it turns out, this fragment is a pretty close (if not perfect) match in size and shape for our cast of Smilodon from Rancholabrean La Brea: Turning to the squamosal, below is the relevant area on our cast Smilodon; note that an additional bone, the tympanic bulla, is cast into this specimen and obscures part of the squamosal:

Turning to the squamosal, below is the relevant area on our cast Smilodon; note that an additional bone, the tympanic bulla, is cast into this specimen and obscures part of the squamosal: Here's the same area with the DVL squamosal superimposed:

Here's the same area with the DVL squamosal superimposed: This appears to be a very close match. There's no single feature that definitively places these bones in Smilodon, but it seems to be a closer match than Panthera onca. Moreover, while jaguars are rare in Southern California and otherwise unknown from Diamond Valley Lake, sabertooth cats are very common in Southern California deposits and are known from several DVL sites. Taken together, I think everything points to this specimen being Smilodon.* Edited to include the correct the range of the modern jaguar.

This appears to be a very close match. There's no single feature that definitively places these bones in Smilodon, but it seems to be a closer match than Panthera onca. Moreover, while jaguars are rare in Southern California and otherwise unknown from Diamond Valley Lake, sabertooth cats are very common in Southern California deposits and are known from several DVL sites. Taken together, I think everything points to this specimen being Smilodon.* Edited to include the correct the range of the modern jaguar.

Fossil Friday - Bison molar

At Diamond Valley Lake, five genera account for 93% of the preserved large animals: Bison, Equus, Camelops, Mammoth, and Paramylodon. Of these five, the most abundant are Bison.The tooth shown above is an upper left 1st molar from a bison. Unfortunately, I photographed it upside down, so even though it's an upper tooth in the image the edge at the top is the chewing surface and the roots are at the bottom. This is the labial view, the side of the tooth closest to the lips.Below is the lingual view, showing the side of the tooth closest to the tongue:

At Diamond Valley Lake, five genera account for 93% of the preserved large animals: Bison, Equus, Camelops, Mammoth, and Paramylodon. Of these five, the most abundant are Bison.The tooth shown above is an upper left 1st molar from a bison. Unfortunately, I photographed it upside down, so even though it's an upper tooth in the image the edge at the top is the chewing surface and the roots are at the bottom. This is the labial view, the side of the tooth closest to the lips.Below is the lingual view, showing the side of the tooth closest to the tongue: Again, the occlusal edge is at the top, roots at the bottom. The reddish-brown protuberance in the middle of the tooth is a column called the style (stylid on the lower teeth). The style is almost always present in the upper and lower molars of Bison, but it's very rare in the closely related cattle genus Bos. So it's a very convenient identification feature (if not necessarily 100% reliable) for distinguishing between Bos and Bison.In occlusal view (below), the style can be seen end-on on the lingual side of the tooth (on the left in this image):

Again, the occlusal edge is at the top, roots at the bottom. The reddish-brown protuberance in the middle of the tooth is a column called the style (stylid on the lower teeth). The style is almost always present in the upper and lower molars of Bison, but it's very rare in the closely related cattle genus Bos. So it's a very convenient identification feature (if not necessarily 100% reliable) for distinguishing between Bos and Bison.In occlusal view (below), the style can be seen end-on on the lingual side of the tooth (on the left in this image): This particular tooth only has very light wear. In a heavily-worn molar, the tooth eventually wears away so much that the occlusal surface of the tooth is level with the tip of the style. The style then begins to wear as well, and becomes visible on the occlusal surface as an isolated ring of enamel. Because the style is not the same shape throughout its length, as wear continues the ring gradually becomes an oval, and then a loop of enamel connected to the rest of the tooth. So the style shape on the occlusal surface give a rapid indication of how worn the tooth is, even is it's still embedded in the socket.This tooth was collected from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. Bison latifrons has not been identified from the West Dam, so this is most likely Bison antiquus. Western Science Center also has teaching kits based on interpretation of bison tooth wear in cast specimens available for purchase.

This particular tooth only has very light wear. In a heavily-worn molar, the tooth eventually wears away so much that the occlusal surface of the tooth is level with the tip of the style. The style then begins to wear as well, and becomes visible on the occlusal surface as an isolated ring of enamel. Because the style is not the same shape throughout its length, as wear continues the ring gradually becomes an oval, and then a loop of enamel connected to the rest of the tooth. So the style shape on the occlusal surface give a rapid indication of how worn the tooth is, even is it's still embedded in the socket.This tooth was collected from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. Bison latifrons has not been identified from the West Dam, so this is most likely Bison antiquus. Western Science Center also has teaching kits based on interpretation of bison tooth wear in cast specimens available for purchase.

Fossil Friday - mastodon vertebra revisited

After a highly successful Science Under the Stars fundraiser, I've tried to get back into the lab to catch up on neglected science work. Administrative duties are still conspiring to keep me chained to the phone and computer, but I have made some progress.Above is a mastodon thoracic vertebrae, one of the same vertebrae featured on Fossil Friday last month. We've removed this vertebra from the field jacket and started repairs and reconstruction.The image above is in posterior view, with anterior to the top. This is an anterior thoracic, with the very tall neural spine typical of that part of the skeleton. There are two prominent articulations on the right side for ribs. One is just below the tip of the transverse process and faces toward the lower right, while the other is the circular depression between the transverse process and the centrum. These two regions actually articulate with different ribs; the transverse process articulates with the tuberculum (or tubercle) of the rib, while the depression adjacent to the centrum articulates with the capitulum (or head) of the next rib.We'll continue cleaning this and the other bones from this jacket in the coming weeks. We should be able to pin down pretty tightly which vertebra in the series this is. Then these will be joining other bones from the same individual in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit.

After a highly successful Science Under the Stars fundraiser, I've tried to get back into the lab to catch up on neglected science work. Administrative duties are still conspiring to keep me chained to the phone and computer, but I have made some progress.Above is a mastodon thoracic vertebrae, one of the same vertebrae featured on Fossil Friday last month. We've removed this vertebra from the field jacket and started repairs and reconstruction.The image above is in posterior view, with anterior to the top. This is an anterior thoracic, with the very tall neural spine typical of that part of the skeleton. There are two prominent articulations on the right side for ribs. One is just below the tip of the transverse process and faces toward the lower right, while the other is the circular depression between the transverse process and the centrum. These two regions actually articulate with different ribs; the transverse process articulates with the tuberculum (or tubercle) of the rib, while the depression adjacent to the centrum articulates with the capitulum (or head) of the next rib.We'll continue cleaning this and the other bones from this jacket in the coming weeks. We should be able to pin down pretty tightly which vertebra in the series this is. Then these will be joining other bones from the same individual in the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit.

Fossil Friday - mammoth tooth

Tomorrow is the Western Science Center's annual fundraiser, Science Under the Stars. That has our entire staff, including me, wrapped up in preparations for 500 guests and a massive benefit auction, so Fossil Friday will necessarily be brief.Above on the left is a partial molar from a Columbian mammoth, Mammuthus columbi, from Pleistocene deposits near Murrieta in Riverside County. As massive as the tooth is, it's incomplete, with the anterior part of the tooth having already worn away. Mammoth teeth (in fact, all the elephants) have enamel arranged in transverse plates that wear to enamel loops on the occlusal surface.The tooth on the right is a cast of a wooly mammoth (M. primigenius) from Alaska. While it's a little difficult to see on the black tooth, the enamel plates on the wooly mammoth are thinner and more numerous than on the Columbian mammoth. This general rule is often used to distinguish between the two species, but as so often seems to be the case, proboscideans are not good at following rules! There is considerable overlap in this character ("lamellar frequency") between Columbian and wooly mammoths. Moreover, it appears that the two species were regularly interbreeding where their ranges overlapped (the apparent hybrids were originally given a different species name, M. jeffersonii). And recent genetic evidence calls into question whether Columbian and wooly mammoths were in fact just different morphs of a single, highly variable species.

Tomorrow is the Western Science Center's annual fundraiser, Science Under the Stars. That has our entire staff, including me, wrapped up in preparations for 500 guests and a massive benefit auction, so Fossil Friday will necessarily be brief.Above on the left is a partial molar from a Columbian mammoth, Mammuthus columbi, from Pleistocene deposits near Murrieta in Riverside County. As massive as the tooth is, it's incomplete, with the anterior part of the tooth having already worn away. Mammoth teeth (in fact, all the elephants) have enamel arranged in transverse plates that wear to enamel loops on the occlusal surface.The tooth on the right is a cast of a wooly mammoth (M. primigenius) from Alaska. While it's a little difficult to see on the black tooth, the enamel plates on the wooly mammoth are thinner and more numerous than on the Columbian mammoth. This general rule is often used to distinguish between the two species, but as so often seems to be the case, proboscideans are not good at following rules! There is considerable overlap in this character ("lamellar frequency") between Columbian and wooly mammoths. Moreover, it appears that the two species were regularly interbreeding where their ranges overlapped (the apparent hybrids were originally given a different species name, M. jeffersonii). And recent genetic evidence calls into question whether Columbian and wooly mammoths were in fact just different morphs of a single, highly variable species.

Fossil Friday - mammoth tusk

I missed last Fossil Friday while I was attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary, which included posters on Diamond Valley Lake mastodon tusks and the Valley of the Mastodons Symposium and Exhibit. But I'm now back in Hemet, and ready for some more Fossil Friday posts!A few months ago I posted about a Columbian mammoth lower jaw from Merced County, collected by PaleoResources during a Caltrans road project. There was actually quite a bit of material recovered during this project, and we're currently in the process of integrating it into the WSC collections. One of the other large pieces is the tusk shown above.This is a typical left tusk from a mammoth, with strong curvature in multiple planes resulting in an open spiral shape. Mastodon tusks, in contrast, tend to be thicker for a given length (at least in males), and curve more strongly in one plane than the other, so the tusk is more of an arc than a spiral. While it's difficult to see from this angle, the tusk shown here has a fairly prominent wear facet at the tip.When PaleoResources dropped off this collection, they indicated that they suspected the mammoth material represented more than one individual, even though there were no duplicate pieces (so that, technically, the minimum number of individuals = 1). I agree with PaleoResources' assessment; I don't see any way such a large tusk could have come from a mammoth as young as the one represented by the lower jaw in the same deposit.This tusk, along with the juvenile lower jaw and an associated mammoth pelvis, are currently on display at the Western Science Center.

I missed last Fossil Friday while I was attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary, which included posters on Diamond Valley Lake mastodon tusks and the Valley of the Mastodons Symposium and Exhibit. But I'm now back in Hemet, and ready for some more Fossil Friday posts!A few months ago I posted about a Columbian mammoth lower jaw from Merced County, collected by PaleoResources during a Caltrans road project. There was actually quite a bit of material recovered during this project, and we're currently in the process of integrating it into the WSC collections. One of the other large pieces is the tusk shown above.This is a typical left tusk from a mammoth, with strong curvature in multiple planes resulting in an open spiral shape. Mastodon tusks, in contrast, tend to be thicker for a given length (at least in males), and curve more strongly in one plane than the other, so the tusk is more of an arc than a spiral. While it's difficult to see from this angle, the tusk shown here has a fairly prominent wear facet at the tip.When PaleoResources dropped off this collection, they indicated that they suspected the mammoth material represented more than one individual, even though there were no duplicate pieces (so that, technically, the minimum number of individuals = 1). I agree with PaleoResources' assessment; I don't see any way such a large tusk could have come from a mammoth as young as the one represented by the lower jaw in the same deposit.This tusk, along with the juvenile lower jaw and an associated mammoth pelvis, are currently on display at the Western Science Center.

Fossil Friday - mastodon vertebrae

Even though the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit is now open, it doesn't mean that our mastodon work has moved to the backburner. On the contrary, we're now doing more mastodon work than ever before!The field jacket shown above is associated with a partial mastodon skeleton currently on display in Valley of the Mastodons; I've previously featured the axis vertebra and the tusks from this mastodon on Fossil Fridays. This jacket has been partially prepared, but there are still several bones present. Some of these are highlighted in the color-coded version below:

Even though the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit is now open, it doesn't mean that our mastodon work has moved to the backburner. On the contrary, we're now doing more mastodon work than ever before!The field jacket shown above is associated with a partial mastodon skeleton currently on display in Valley of the Mastodons; I've previously featured the axis vertebra and the tusks from this mastodon on Fossil Fridays. This jacket has been partially prepared, but there are still several bones present. Some of these are highlighted in the color-coded version below: The blue area is (I think) the first cervical vertebra, or atlas. Yellow is a rib, and red are two thoracic vertebrae. There are also several unmarked and unidentified fragments. The thoracic vertebrae have the very tall neural spines that are typical of anterior thoracics in animals with large, heavy heads.We'll be removing these bones over the next few weeks, and as they're completed they'll be moving into the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit along with the rest of this mastodon.Next week I'll be in Calgary, attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting. Many paleontologists will be live-tweeting the conference, including me (at least on occasion) and @MaxMastodon.

The blue area is (I think) the first cervical vertebra, or atlas. Yellow is a rib, and red are two thoracic vertebrae. There are also several unmarked and unidentified fragments. The thoracic vertebrae have the very tall neural spines that are typical of anterior thoracics in animals with large, heavy heads.We'll be removing these bones over the next few weeks, and as they're completed they'll be moving into the Valley of the Mastodons exhibit along with the rest of this mastodon.Next week I'll be in Calgary, attending the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting. Many paleontologists will be live-tweeting the conference, including me (at least on occasion) and @MaxMastodon.