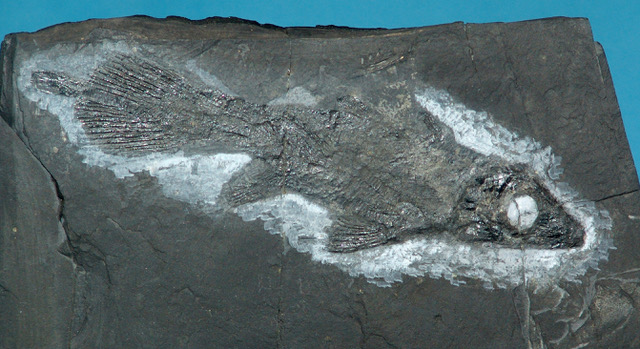

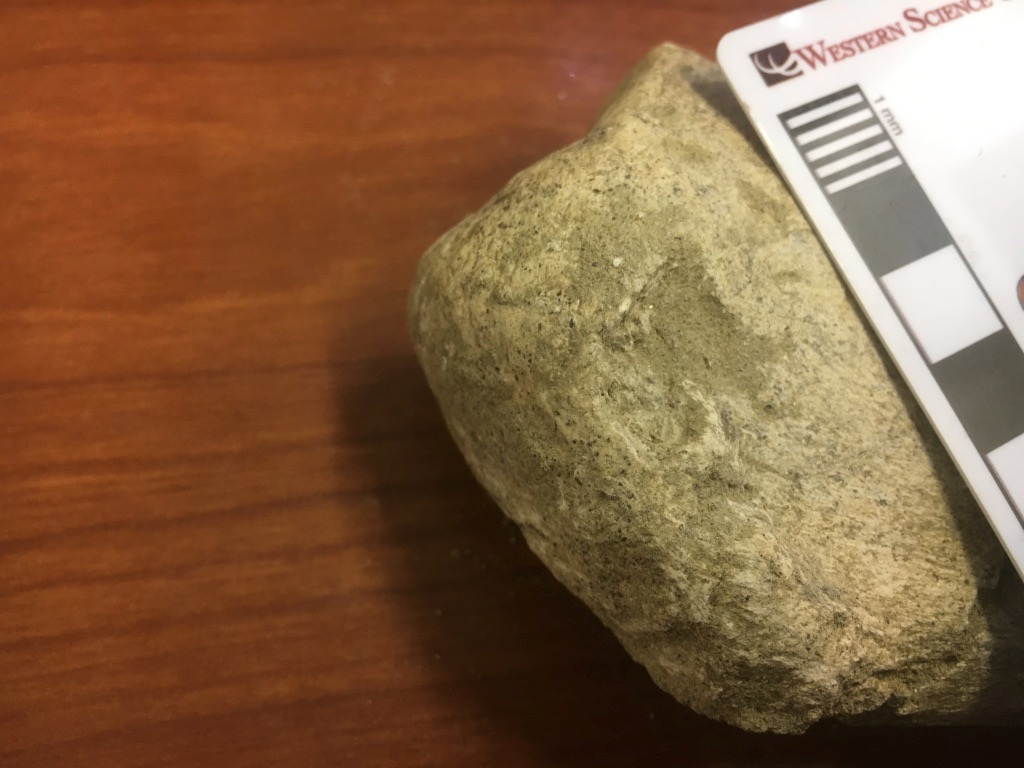

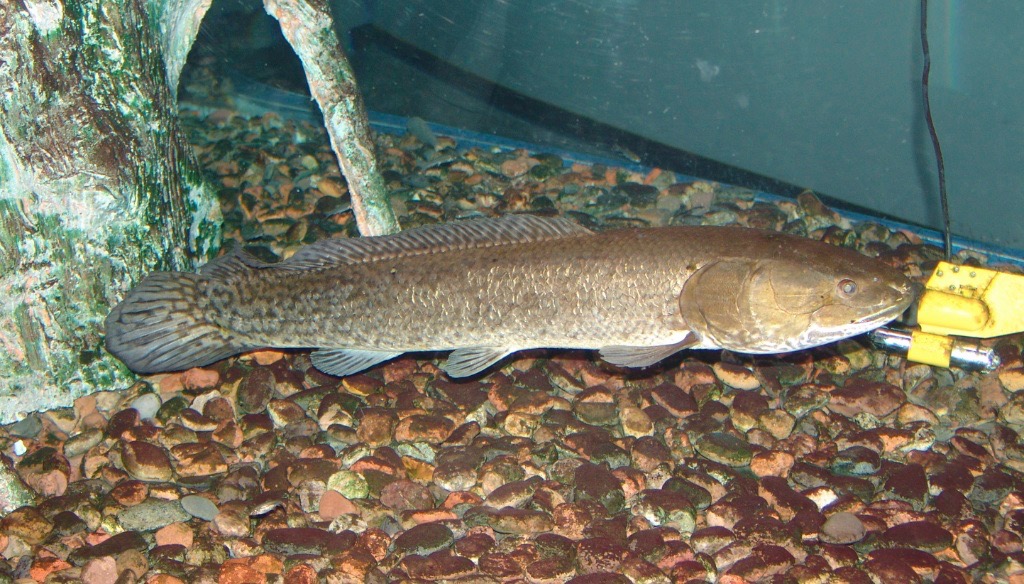

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

In 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a naturalist at the East London Museum in South Africa, discovered a bizarre fish in a fisherman's haul. This remarkable fish was later given the genus name Latimeria to honor the woman who first recognized its importance. Courtenay-Latimer's discovery was the first indication that an ancient type of fish, thought to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, was alive and well in the modern ocean. Latimeria is the living coelacanth.Coelacanths have a long fossil record, going all the way back to the Devonian Period, more than 400 million years ago. They were extremely successful, inhabiting both freshwater and saltwater, evolving a great range of body shapes, and in some cases, growing to huge sizes of 15 feet or more. The Western Science Center's coelacanth fossil was discovered in New Jersey by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary Garbani.This little fossil fish probably belongs to the genus Diplurus, which lived during the Early Jurassic Epoch, around 200 million years ago. In the photo, the skull is towards the upper left, with the tail in the bottom right. Part of the vertebral column is visible behind the skull, as well as parts of at least two fins. The second photo is a much more complete specimen of Diplurus, photographed by Alton Dooley at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, showing the full body shape.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - champsosaur vertebrae

Driven by a surge in volcanic activity and a devastating asteroid impact, the mass extinction 66 million years ago was one of the most cataclysmic events in Earth's long history. On land and in the sea, vast numbers of animals and plants went extinct. Among the victims were the dinosaurs, except for modern birds; the great marine reptiles; and the ammonites, coil-shelled relatives of squid and octopus. Among the survivors were the ancestors of modern birds, crocodilians, mammals, and other organisms that would shape the ecology of the planet for the next 66 million years.However, not all the animal groups that survived through the mass extinction would make it to the present day. One such animal is Champsosaurus. Champsosaurus fossils are common in the western United States and Canada, in rocks that date to just before the mass extinction and just after the extinction. Champsosaurus hung on until around 55 million years ago, when it finally went extinct.These are four Champsosaurus vertebrae from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, found by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. The two vertebrae on the left are shown in bottom view, and the two vertebrae on the right are in top view. Champsosaurus lived in freshwater and used its long toothy snout to catch fish and other prey. It could grow to around six feet long and was built a little like a small crocodile (example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History):

Driven by a surge in volcanic activity and a devastating asteroid impact, the mass extinction 66 million years ago was one of the most cataclysmic events in Earth's long history. On land and in the sea, vast numbers of animals and plants went extinct. Among the victims were the dinosaurs, except for modern birds; the great marine reptiles; and the ammonites, coil-shelled relatives of squid and octopus. Among the survivors were the ancestors of modern birds, crocodilians, mammals, and other organisms that would shape the ecology of the planet for the next 66 million years.However, not all the animal groups that survived through the mass extinction would make it to the present day. One such animal is Champsosaurus. Champsosaurus fossils are common in the western United States and Canada, in rocks that date to just before the mass extinction and just after the extinction. Champsosaurus hung on until around 55 million years ago, when it finally went extinct.These are four Champsosaurus vertebrae from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, found by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. The two vertebrae on the left are shown in bottom view, and the two vertebrae on the right are in top view. Champsosaurus lived in freshwater and used its long toothy snout to catch fish and other prey. It could grow to around six feet long and was built a little like a small crocodile (example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History):

Fossil Friday - antilocaprid tooth

Yesterday was World Giraffe Day. Giraffes are members of a once-large superfamily of artiodactyls called the Giraffoidea, that now includes only three extant genera: Giraffa, Okapaia (okapis), and Antilocapra (pronghorns). While giraffes and okapis are only found in the Old World, antilocaprids are native to North America.Antilocaprids have an extensive fossil record, as as recently as the Pleistocene they were much more diverse. Several species are known from the Pleistocene of Southern California, and there are a few specimens in the collections at the Western Science Center.

Yesterday was World Giraffe Day. Giraffes are members of a once-large superfamily of artiodactyls called the Giraffoidea, that now includes only three extant genera: Giraffa, Okapaia (okapis), and Antilocapra (pronghorns). While giraffes and okapis are only found in the Old World, antilocaprids are native to North America.Antilocaprids have an extensive fossil record, as as recently as the Pleistocene they were much more diverse. Several species are known from the Pleistocene of Southern California, and there are a few specimens in the collections at the Western Science Center. Above is a partial lower right third molar, seen in lingual view. This tooth is consistent with Antilocapra itself, but could also represent the similar-sized Tetrameryx, which is also known from the southwest. This tooth is our only record of an antilocaprid from the Late Pleistocene deposits in the Harveston neighborhood of Temecula, in southwestern Riverside County.We've made a 3D model of this tooth available for download at Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly.6zQBw.

Above is a partial lower right third molar, seen in lingual view. This tooth is consistent with Antilocapra itself, but could also represent the similar-sized Tetrameryx, which is also known from the southwest. This tooth is our only record of an antilocaprid from the Late Pleistocene deposits in the Harveston neighborhood of Temecula, in southwestern Riverside County.We've made a 3D model of this tooth available for download at Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly.6zQBw.

Fossil Friday - Palm Frond

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

I just returned from 18 days of field work in the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico.A team of staff and volunteers from Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society collected over half a ton of fossils, including dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles. All these fossils will be prepped, curated, and studied at Western Science Center over the next few years.While digging through the hard mudstone layers of the Menefee Formation, we invariably encounter abundant plant fossils. Most of these consist of shards of stems and leaves, but many others should be identifiable. In this image are two pieces of mudstone collected at one of our dinosaur quarries. The piece on the left is covered in fragments of stems and leaves, with a more complete leaf in the upper left corner. On the right is a slice of mudstone with part of a palm leaf preserved.Fossil plants are an integral part of reconstructing and imagining ancient ecosystems. Analysis of plant fossils such as these will help reveal what the climate, environment, and ecology of the Menefee Formation were like 80 million years ago.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - mastodon palate

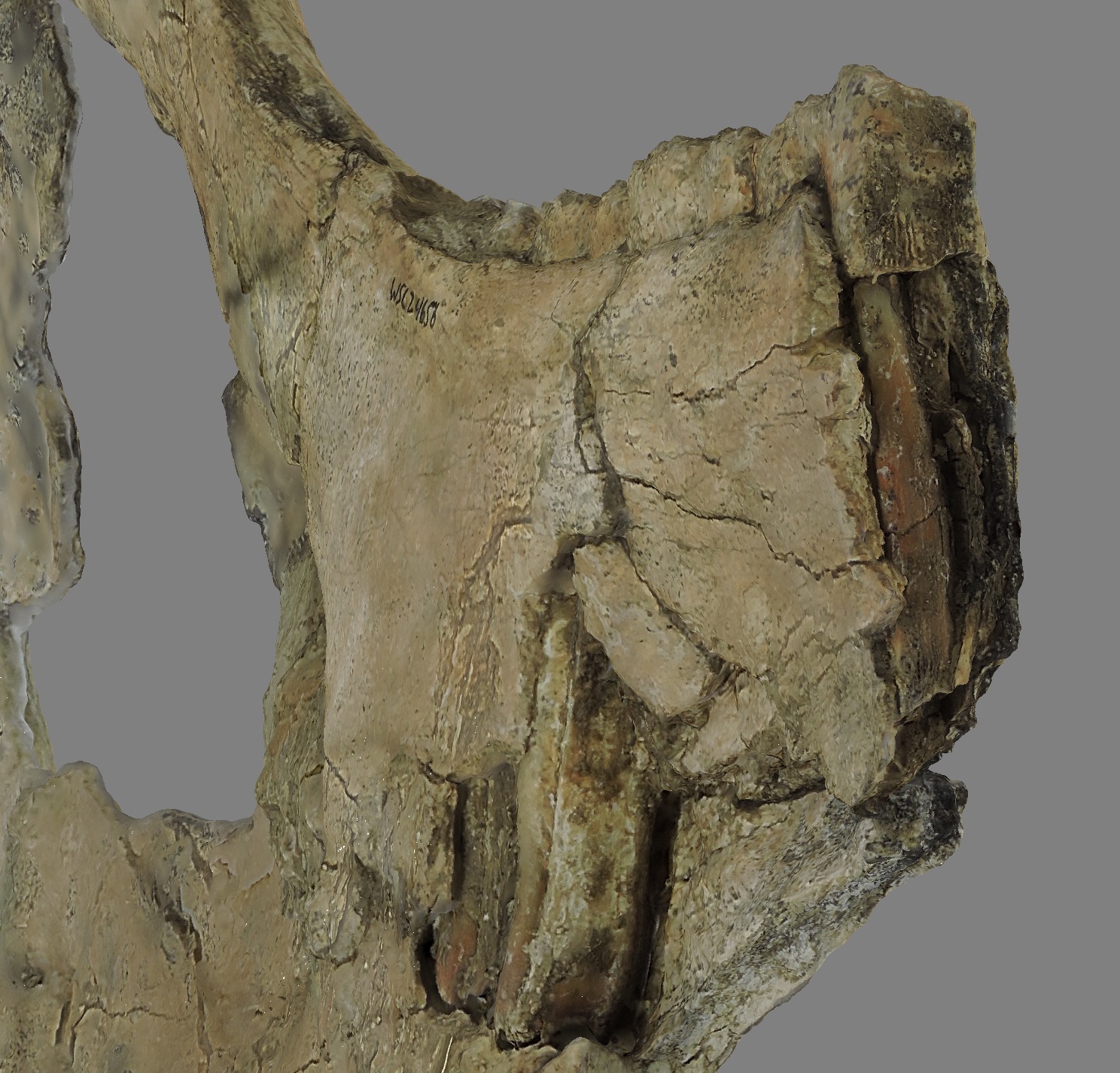

The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has closed, and most of out mastodon remains have been moved back to the museum's repository. But that doesn't mean they're forgotten, or that work on them has stopped!This specimen is a fragment of a mastodon palate, with the anterior end on the left. Most of the left side of the palate is missing, but the right side (at the bottom of the image) includes the complete 2nd and 3rd molars. Even a small fragment like this tells us quite a bit about mastodons.Like other advanced proboscideans, mastodons replaced their teeth horizontally instead of vertically like most mammals. That means that during the mastodon's life it gradually works it's way through six teeth in each quarter jaw, one after another - the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th premolars, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars (we're ignoring the tusks here, which are also teeth). With this pattern of tooth replacement, by looking at which teeth are present in the mouth and how worn the teeth are, we can make a reasonably precise estimate of how old the mastodon was when it died.In 1966, British biologist Richard Laws published a detailed description of how tooth wear and replacement rates relate to age in African elephants, which has become the standard starting point for estimating proboscidean ages. He divided the elephant life cycle into 30 tooth wear stages, which are now called Laws groups. So, for example, an African elephant with the 4th premolar heavily worn and the 1st molar just about to erupt would be in Laws group VII, which would make it 6 years old, ± 1 year.With some limitations, this same system works pretty well for mastodons even though they're only distantly related to elephants. Because there is some uncertainty involved, when applied to extinct elephants the age indicated by the Laws group is usually expressed in terms of AEY (African Equivalent Years), the age that an African elephant would be in the same wear state.So how about this mastodon? The 2nd molar is still present, but is almost completely worn away; there is only a thin band of enamel remaining around the edges. The 3rd molar shows lots of wear on the 1st loph at the front of the tooth, somewhat less on the 2nd loph, light wear on the 3rd, and little or no wear on the 4th. That puts this mastodon into Laws group 22, with an age of 39 ± 2 AEY, a fully mature but not yet elderly mastodon. We actually have several mastodons from Diamond Valley Lake that fall into Laws group 22, including Max, our largest and best-preserved skull.This particular mastodon was discovered at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, making it between about 14,000-20,000 years old. Reference:Laws, R. M., 1966. Age criteria for the African elephant, Loxodonta a. africana. East African Wildlife Journal 4:1-37.

The Valley of the Mastodons exhibit has closed, and most of out mastodon remains have been moved back to the museum's repository. But that doesn't mean they're forgotten, or that work on them has stopped!This specimen is a fragment of a mastodon palate, with the anterior end on the left. Most of the left side of the palate is missing, but the right side (at the bottom of the image) includes the complete 2nd and 3rd molars. Even a small fragment like this tells us quite a bit about mastodons.Like other advanced proboscideans, mastodons replaced their teeth horizontally instead of vertically like most mammals. That means that during the mastodon's life it gradually works it's way through six teeth in each quarter jaw, one after another - the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th premolars, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars (we're ignoring the tusks here, which are also teeth). With this pattern of tooth replacement, by looking at which teeth are present in the mouth and how worn the teeth are, we can make a reasonably precise estimate of how old the mastodon was when it died.In 1966, British biologist Richard Laws published a detailed description of how tooth wear and replacement rates relate to age in African elephants, which has become the standard starting point for estimating proboscidean ages. He divided the elephant life cycle into 30 tooth wear stages, which are now called Laws groups. So, for example, an African elephant with the 4th premolar heavily worn and the 1st molar just about to erupt would be in Laws group VII, which would make it 6 years old, ± 1 year.With some limitations, this same system works pretty well for mastodons even though they're only distantly related to elephants. Because there is some uncertainty involved, when applied to extinct elephants the age indicated by the Laws group is usually expressed in terms of AEY (African Equivalent Years), the age that an African elephant would be in the same wear state.So how about this mastodon? The 2nd molar is still present, but is almost completely worn away; there is only a thin band of enamel remaining around the edges. The 3rd molar shows lots of wear on the 1st loph at the front of the tooth, somewhat less on the 2nd loph, light wear on the 3rd, and little or no wear on the 4th. That puts this mastodon into Laws group 22, with an age of 39 ± 2 AEY, a fully mature but not yet elderly mastodon. We actually have several mastodons from Diamond Valley Lake that fall into Laws group 22, including Max, our largest and best-preserved skull.This particular mastodon was discovered at the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake, making it between about 14,000-20,000 years old. Reference:Laws, R. M., 1966. Age criteria for the African elephant, Loxodonta a. africana. East African Wildlife Journal 4:1-37.

Fossil Friday - Triceratops Teeth

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - Palm Leaf

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

The fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals certainly hog the spotlight, and they are spectacular. But alongside the bones of giants such as Tyrannosaurus is a very different, much more abundant type of fossil: ancient plants. Paleobotany, the study of fossil plants, is a vital part of understanding Earth history. Fossil plants provide data on bygone environments, ecology, and climate.This fossil is the impression of a 67-million-year-old palm leaf. It was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. The living plant probably looked much like modern palm trees, and points to a much warmer climate in Montana during the Late Cretaceous Epoch than today. Next time you see a living palm tree swaying in the breeze, imagine a T. rex under it seeking shade from the midday sun. Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Horse molar

One thing has become quickly obvious as we've been examining the Harveston fossil collection: there are a lot of horses.This is one of several isolated horse teeth from Harveston. This specimen is an upper right 1st molar, and is of particular interest because it is quite a bit smaller than most of our Harveston horses, as can be seen below:

One thing has become quickly obvious as we've been examining the Harveston fossil collection: there are a lot of horses.This is one of several isolated horse teeth from Harveston. This specimen is an upper right 1st molar, and is of particular interest because it is quite a bit smaller than most of our Harveston horses, as can be seen below: It turns out there were actually two species of horses at Harveston. The larger and much more common one is Equus occidentalis, while the smaller, rare species is generally called Equus conversidens (there are some nomenclatural issues with this name and with Equus species in general, but I'm not going to get into that here). E. conversidens makes up perhaps 5% of the Harveston horses. This seems to be a general trend for southern California sites, including Diamond Valley Lake, with both species generally present, and E. occidentalis being much more common.We've made a 3D scan of this E. conversidens tooth (WSC 24676) available for download on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6yJNq.

It turns out there were actually two species of horses at Harveston. The larger and much more common one is Equus occidentalis, while the smaller, rare species is generally called Equus conversidens (there are some nomenclatural issues with this name and with Equus species in general, but I'm not going to get into that here). E. conversidens makes up perhaps 5% of the Harveston horses. This seems to be a general trend for southern California sites, including Diamond Valley Lake, with both species generally present, and E. occidentalis being much more common.We've made a 3D scan of this E. conversidens tooth (WSC 24676) available for download on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6yJNq.

Fossil Friday - horse dentary

Fossil Friday this week continues our examination of Pleistocene specimens from Temecula Valley, this time with a partial lower jaw from the horse Equus occidentalis.The image above was prepared for our poster at next month's regional GSA meeting in Flagstaff. It shows the dentary in medial, dorsal, and lateral views. The scale bar is 10 cm. In the dorsal view, you can see the occlusal surfaces of the last four teeth in the jaw, which in this case are (from front to back) the 4th deciduous premolar, and molars 1, 2, and 3. The 3rd molar had only just started to erupt, suggesting that this horse was about 3.5 years old when it died. In an oblique anteromedial view (actually a screenshot from a photogrammetric model), you can see the unerupted 4th premolar underneath the 4th deciduous premolar, and, in the background, the deep crown of the 2nd molar where the side of the jaw is broken:

Fossil Friday this week continues our examination of Pleistocene specimens from Temecula Valley, this time with a partial lower jaw from the horse Equus occidentalis.The image above was prepared for our poster at next month's regional GSA meeting in Flagstaff. It shows the dentary in medial, dorsal, and lateral views. The scale bar is 10 cm. In the dorsal view, you can see the occlusal surfaces of the last four teeth in the jaw, which in this case are (from front to back) the 4th deciduous premolar, and molars 1, 2, and 3. The 3rd molar had only just started to erupt, suggesting that this horse was about 3.5 years old when it died. In an oblique anteromedial view (actually a screenshot from a photogrammetric model), you can see the unerupted 4th premolar underneath the 4th deciduous premolar, and, in the background, the deep crown of the 2nd molar where the side of the jaw is broken: We've made a photogrammetric model of this specimen, and printed a 3d replica that we've already started using in programming:

We've made a photogrammetric model of this specimen, and printed a 3d replica that we've already started using in programming: The 3D file of this specimen is available for download at WSC's Sketchfab site at https://skfb.ly/6yCx8.

The 3D file of this specimen is available for download at WSC's Sketchfab site at https://skfb.ly/6yCx8.

Fossil Friday - horse scapula

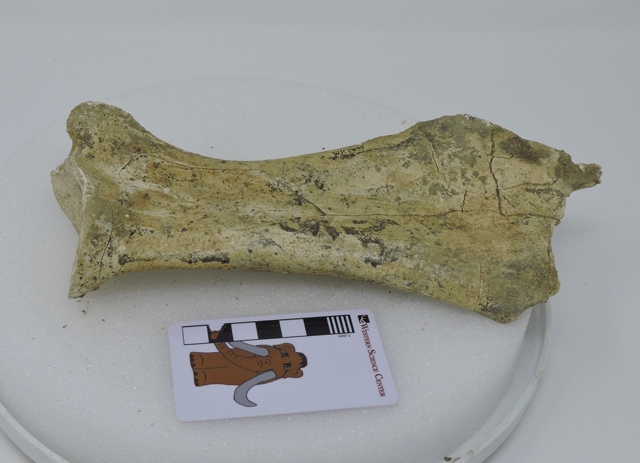

This week we continue our documentation of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston section of Murrieta, California, with a horse scapula.This specimen is a partial right scapula, shown above in medial view. It's missing a small part of the dorsal edge, on the right in the photo. The part of the scapula is cartilaginous in young animals, and actually only ossifies fairly late in ontogeny, so it's not unusual to be missing this area.

This week we continue our documentation of Pleistocene fossils from the Harveston section of Murrieta, California, with a horse scapula.This specimen is a partial right scapula, shown above in medial view. It's missing a small part of the dorsal edge, on the right in the photo. The part of the scapula is cartilaginous in young animals, and actually only ossifies fairly late in ontogeny, so it's not unusual to be missing this area. The lateral view is shown above, with anterior at the bottom (this image is missing the scale bar because these are part of a set used to produce a photogrammetric model). The surface on the left is the edge of the glenoid fossa, the articulation with the head of the humerus (the "shoulder socket"). A bone ridge, called the scapular spine, is pointing straight at the camera and divides the scapula into concave anterior and posterior surfaces. The anterior portion is called the supraspinatus fossa, while the posterior part is the infraspinatus fossa; each serves as the attachment points for muscles of the same names, that are involved in rotating the forelimb.I've uploaded a 3D model of this specimen on Sketchfab, available at https://skfb.ly/6y9VM.

The lateral view is shown above, with anterior at the bottom (this image is missing the scale bar because these are part of a set used to produce a photogrammetric model). The surface on the left is the edge of the glenoid fossa, the articulation with the head of the humerus (the "shoulder socket"). A bone ridge, called the scapular spine, is pointing straight at the camera and divides the scapula into concave anterior and posterior surfaces. The anterior portion is called the supraspinatus fossa, while the posterior part is the infraspinatus fossa; each serves as the attachment points for muscles of the same names, that are involved in rotating the forelimb.I've uploaded a 3D model of this specimen on Sketchfab, available at https://skfb.ly/6y9VM.

Fossil Friday - Snake Vertebra

In the opinion of this naturalist, snakes are among the most elegant animals ever to have evolved. The fossil record of extinct snakes was poorly known for a long time. However, recent discoveries have revealed that a diverse array of early snakes lived alongside the dinosaurs, as far back in time as the Middle Jurassic Epoch, over 165 million years ago. The earliest known snake is Eophis underwoodi, from the Middle Jurassic of England: http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms6996Today's Fossil Friday subject is a fossil snake in the Western Science Center's collection. This is a vertebra of Coniophis precedens, a snake that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch, about 67 million years ago, alongside much bigger reptiles such as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. This specimen was collected by the late Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary.

In the opinion of this naturalist, snakes are among the most elegant animals ever to have evolved. The fossil record of extinct snakes was poorly known for a long time. However, recent discoveries have revealed that a diverse array of early snakes lived alongside the dinosaurs, as far back in time as the Middle Jurassic Epoch, over 165 million years ago. The earliest known snake is Eophis underwoodi, from the Middle Jurassic of England: http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms6996Today's Fossil Friday subject is a fossil snake in the Western Science Center's collection. This is a vertebra of Coniophis precedens, a snake that lived during the Late Cretaceous Epoch, about 67 million years ago, alongside much bigger reptiles such as Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. This specimen was collected by the late Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, and donated to the museum by his wife, Mary.

These early snakes were not venomous, but instead killed their prey by constriction like living pythons and boas. Another Late Cretaceous snake, Sanajeh indicus from India, seems to have habitually preyed upon hatchling long-necked sauropod dinosaurs. Three skeletons of this snake have been discovered associated with fossils of sauropod nests, eggs, and hatchlings: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1000322

Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - juvenile Tyrannosaurus

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - camel elbow

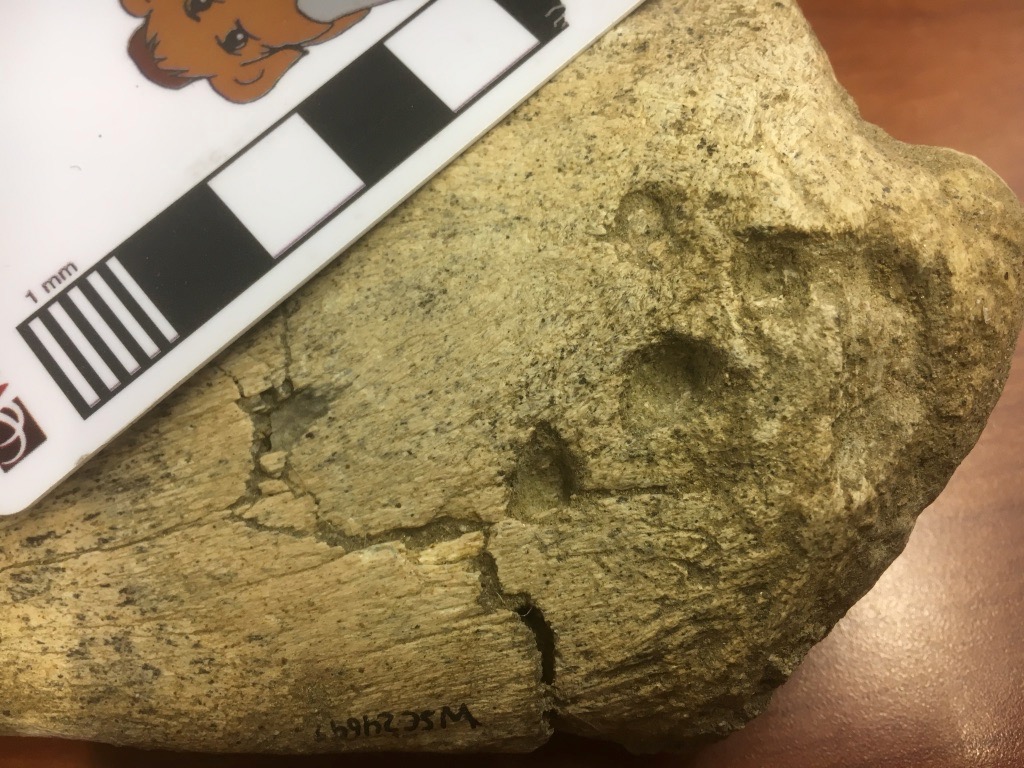

We're continuing our focus on Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, California this week with a single bone fragment that has a lot going on.This bone is labeled in our collections as an ulna from Equus, a horse. It is indeed part of a left ulna, one of the bones from the forearm. More specifically, it's the olecranon process, the proximal end of the ulna that forms the point of the elbow. The triceps muscle attaches to the olecranon process, allowing you to straighten your arm (or front leg, in this case). However, after spending several hours comparing this to various publications and our Diamond Valley Lake collections, I'm not convinced it's a horse.For an olecranon process of this size, there are really only three likely animals from the Pleistocene of Southern California it could belong to: horse, camel, and bison. Everything else is either much larger (mammoth, mastodon) or much smaller (mule deer). (OK, to be fair, short-faced bears and ground sloths are in this size range, but their ulnae look nothing like this.) Horses, camels, and bison are all known from this site, but while it's a little on the small side, this bone is the best match with the western camel, Camelops hesternus.There is another interesting feature on this bone. Notice the four circular depressions near the tip (on the right). Here's a closeup:

We're continuing our focus on Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, California this week with a single bone fragment that has a lot going on.This bone is labeled in our collections as an ulna from Equus, a horse. It is indeed part of a left ulna, one of the bones from the forearm. More specifically, it's the olecranon process, the proximal end of the ulna that forms the point of the elbow. The triceps muscle attaches to the olecranon process, allowing you to straighten your arm (or front leg, in this case). However, after spending several hours comparing this to various publications and our Diamond Valley Lake collections, I'm not convinced it's a horse.For an olecranon process of this size, there are really only three likely animals from the Pleistocene of Southern California it could belong to: horse, camel, and bison. Everything else is either much larger (mammoth, mastodon) or much smaller (mule deer). (OK, to be fair, short-faced bears and ground sloths are in this size range, but their ulnae look nothing like this.) Horses, camels, and bison are all known from this site, but while it's a little on the small side, this bone is the best match with the western camel, Camelops hesternus.There is another interesting feature on this bone. Notice the four circular depressions near the tip (on the right). Here's a closeup: There are a few comparable depressions on the other side:

There are a few comparable depressions on the other side: These appear to be bite marks, from some carnivoran chewing on the end of the bone. There are several other scrapes that appear to be gnaw marks. So far we have not identified any carnivoran bones from this site, but they certainly made their presence felt.We have scanned and 3D-printed this bone (print shown below with the original), and the scans can be viewed on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6xNMM.

These appear to be bite marks, from some carnivoran chewing on the end of the bone. There are several other scrapes that appear to be gnaw marks. So far we have not identified any carnivoran bones from this site, but they certainly made their presence felt.We have scanned and 3D-printed this bone (print shown below with the original), and the scans can be viewed on Sketchfab at https://skfb.ly/6xNMM.

Fossil Friday - amiid fish jaws

At the close of the age of dinosaurs in North America, dry land was prowled by a variety of large and small dinosaurian predators, such as Tyrannosaurus and dromaeosaurs, a.k.a. the raptors. The freshwater streams and lakes were home to very different, but no less voracious, meat-eaters. These bone fragments are pieces of the lower jaws of amiid fish. Amiids are a group of bony fishes with a long fossil record, but which today are restricted to a single surviving species, the bowfin (Amia calva), which hunts in the waterways of eastern North America. (Example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History.)

At the close of the age of dinosaurs in North America, dry land was prowled by a variety of large and small dinosaurian predators, such as Tyrannosaurus and dromaeosaurs, a.k.a. the raptors. The freshwater streams and lakes were home to very different, but no less voracious, meat-eaters. These bone fragments are pieces of the lower jaws of amiid fish. Amiids are a group of bony fishes with a long fossil record, but which today are restricted to a single surviving species, the bowfin (Amia calva), which hunts in the waterways of eastern North America. (Example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History.) These two fragments of lower jaws do not contain any preserved teeth, but clearly show the empty sockets for the teeth. Amiids are carnivorous, and wield a mouth full of formidable teeth for snaring prey, as shown in this bowfin skull at Ohio State University:

These two fragments of lower jaws do not contain any preserved teeth, but clearly show the empty sockets for the teeth. Amiids are carnivorous, and wield a mouth full of formidable teeth for snaring prey, as shown in this bowfin skull at Ohio State University: https://u.osu.edu/biomuseum/olympus-digital-camera-6/These jaw fragments were collected by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, which dates to the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 67 million years ago. They were donated to the Western Science Center by Mary Garbani.

https://u.osu.edu/biomuseum/olympus-digital-camera-6/These jaw fragments were collected by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, which dates to the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 67 million years ago. They were donated to the Western Science Center by Mary Garbani.

Fossil Friday - horse molar

As we continue to work on WSC's collection of Late Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, it has become clear that, while the collection my be taxonomically diverse, it contains a lot of horse bones!The specimen shown above is a lower right first molar of the horse Equus occidentalis in lateral (labial) view. On the left is an unpainted 3D print of the same specimen. Below is the same specimen in occlusal view:

As we continue to work on WSC's collection of Late Pleistocene fossils from Murrieta, it has become clear that, while the collection my be taxonomically diverse, it contains a lot of horse bones!The specimen shown above is a lower right first molar of the horse Equus occidentalis in lateral (labial) view. On the left is an unpainted 3D print of the same specimen. Below is the same specimen in occlusal view: Horses are highly hypsodont, meaning they have very tall, high-crowned teeth. As you can see in the lateral view at the top, we have both the roots and the occlusal surface preserved, showing that we have the whole tooth (it's not broken), yet the tooth is quite short. That's because almost this entire tooth has been worn away, indicating that it came from a very elderly horse.We've obviously scanned this tooth, since we've 3D-printed it. We've also made the scan available on Sketchfab:https://skfb.ly/6xyuR

Horses are highly hypsodont, meaning they have very tall, high-crowned teeth. As you can see in the lateral view at the top, we have both the roots and the occlusal surface preserved, showing that we have the whole tooth (it's not broken), yet the tooth is quite short. That's because almost this entire tooth has been worn away, indicating that it came from a very elderly horse.We've obviously scanned this tooth, since we've 3D-printed it. We've also made the scan available on Sketchfab:https://skfb.ly/6xyuR

Fossil Friday - freshwater snail

The world of the dinosaurs was populated by some of the most gargantuan and charismatic animals ever to roam our planet. It is easy to forget that the Mesozoic Era was just as rich with all sorts of life as our modern world. This is the shell of a freshwater snail called Campeloma. This shell was collected by the late Harley Garbani and is part of a collection donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.This Campeloma was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and is about 67 million years old (Late Cretaceous Epoch). While this little snail scooted along the bottom of ponds and streams, the last of the giant dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus andTriceratops, thundered across the land. Living species of Campeloma still inhabit freshwater environments in the United States and Canada.

The world of the dinosaurs was populated by some of the most gargantuan and charismatic animals ever to roam our planet. It is easy to forget that the Mesozoic Era was just as rich with all sorts of life as our modern world. This is the shell of a freshwater snail called Campeloma. This shell was collected by the late Harley Garbani and is part of a collection donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.This Campeloma was found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and is about 67 million years old (Late Cretaceous Epoch). While this little snail scooted along the bottom of ponds and streams, the last of the giant dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus andTriceratops, thundered across the land. Living species of Campeloma still inhabit freshwater environments in the United States and Canada.

Fossil Friday -crocodilian teeth

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Fossil Friday - horse lunate

We're continuing our efforts to document an describe the fauna from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, a small but diverse collection that appears to be the only Rancholabrean-Age site in Murrieta. The bone shown here is the left lunate of a horse (Equus sp.), with the original bone on the left and a 3D print on the right. The lunate is one of 6 small bones that form the wrist. In horses they are blocky, tightly interlocking bones that can support the stress of holding the weight of a running horse. Unlike primates, which have highly mobile wrists, the horse wrist has essentially no ability to move side-to-side, as is limited to fore-and-aft motion, making it more stable during running.We're planning to scan and print as many of the Harveston bones as possible. The paint job on this print is too dark, so I need to lighten it a bit. O

We're continuing our efforts to document an describe the fauna from the Harveston neighborhood of Murrieta, a small but diverse collection that appears to be the only Rancholabrean-Age site in Murrieta. The bone shown here is the left lunate of a horse (Equus sp.), with the original bone on the left and a 3D print on the right. The lunate is one of 6 small bones that form the wrist. In horses they are blocky, tightly interlocking bones that can support the stress of holding the weight of a running horse. Unlike primates, which have highly mobile wrists, the horse wrist has essentially no ability to move side-to-side, as is limited to fore-and-aft motion, making it more stable during running.We're planning to scan and print as many of the Harveston bones as possible. The paint job on this print is too dark, so I need to lighten it a bit. O

Fossil Friday - lizard vertebra

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat.

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat. By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Smilodon femur

Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image):

Carnivores make up a relatively small percentage of any stable ecosystem; the principle of Conservation of Mass and Energy really doesn't allow for any other possibility. As a result, carnivores generally make up a tiny percentage of the fossils found in most deposits (although there are exceptions, such as predator traps like Rancho La Brea). Nevertheless, sometimes paleontologists get lucky and carnivores turn up in herbivore-dominated deposits. Western Science Center's collection of Early Pleistocene fossils from San Timoteo Canyon is dominated by horses and rodents, with a smattering of other herbivorous taxa. But there are several good carnivoran remains, including a partial skeleton of the sabertooth cat Smilodon. The fragment shown above is the distal end of the right femur, showing part of the knee joint. Compare it to the left femur of a Smilodon from Rancho La Brea, below (since they're opposite sides it's a mirror image): These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.

These specimens are broadly similar, although there are some detail differences in shape (the projecting piece at the top of the San Timoteo specimen is displaced from its correct position). The San Timoteo specimen is also a bit smaller than the Rancho La Brea one. This isn't a big surprise; the San Timoteo skeleton is thought to be Smilodon gracilis, the ancestor to the later, larger Smilodon fatalis found at Rancho La Brea.We recently made 3D scans of this bone, and produced a 3D print (below). At some point in the near future, we'll be making the scans of this and other S. gracilis bones available online.